In the Lori Valley there’ll be a ground frost

As a result of the Karabakh conflict, around 200,000 ethnic Azerbaijanis who lived in Armenia became refugees.

For almost 30 years now there has been no contact between people from Azerbaijan and Armenia. During that time a whole generation has grown up knowing only a white space on the map instead of a neighbouring country.

But there are still people living in Azerbaijan today whose childhood memories are from Armenia.

•The Azerbaijani trail in Kapan

•Karabakh in the everyday lives of Azerbaijanis

“In the Lori Valley there’ll be a ground frost.” That’s how the weather forecast that followed the news back in Soviet times would describe the multitude of small settlements in northern Armenia. Azerbaijani, Armenian and Molokan families all lived together in these towns and villages.

Sona remembers the village of her birth, 25 kilometres from the Armenian border with Georgia.

“All around there were mountains, the air was crystal clear. The rivers ran so pure you could see trout swimming in them. We children used to try and catch them with our hands and sometimes we even succeeded.”

In the village there were 20 Azerbaijani families, the same number of Armenians and around 10 Russian (Molokan) families.

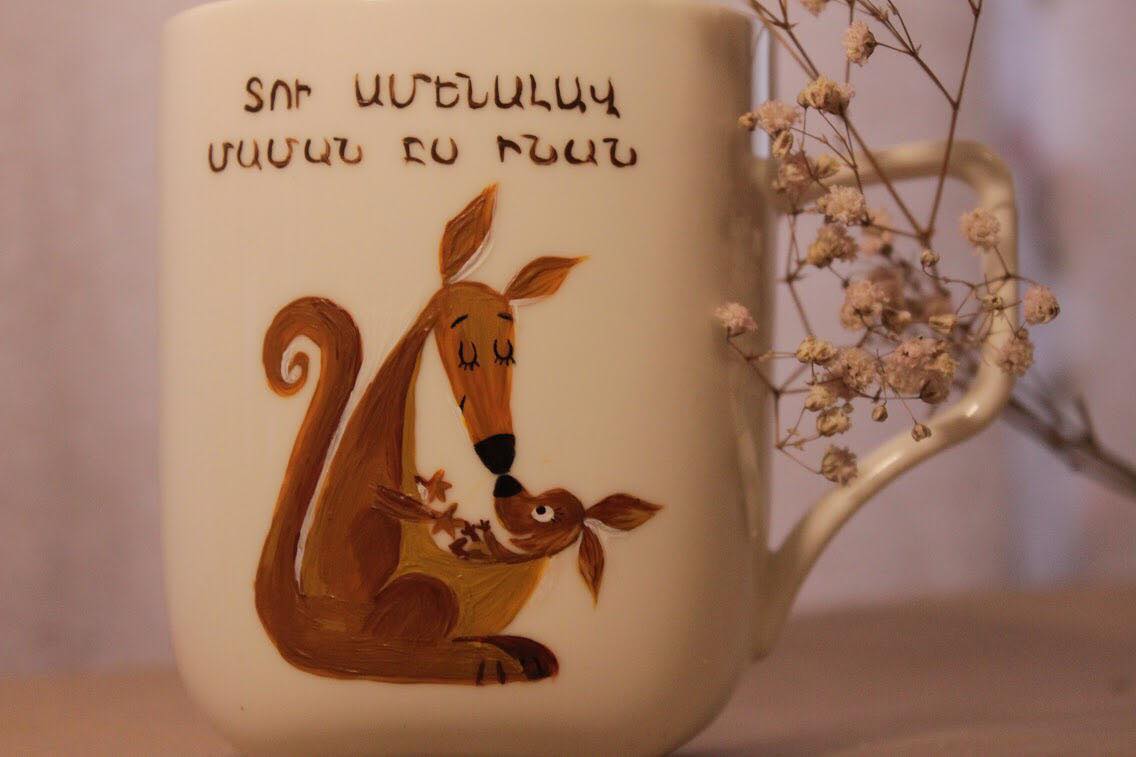

From a family archive

Sona lived there for 19 years before going away to study in Russia. She returned to her home village every year until the beginning of the war. Most of her memories of Armenia are from her childhood.

“It could snow as early as November. We didn’t have much in the way of entertainment – when it’s that cold all you can really do is go and call on people. I used to go to my friend Rima’s house and she’d come to mine.

This is how we got to know each other: before the age of seven I could only speak Azerbaijani and she could only speak Armenian and so the only way we could communicate was through gestures.

For example, I had long hair and hers was short and she wanted to tell me how much she liked my hair. She touched her own hair and frowned and then touched mine and smiled in approval.

Then she gave me sweets and I gave her apples from our garden. The next day she brought a bucket of carrots from their garden and I explained in my broken Russian that I’d never tasted carrots before and I was really happy to receive her gift.

By the time we were in the third class at school we could speak Russian quite well and we became inseparable. Rima’s mother said, “I have five daughters and you’re my sixth”. Mine also knew how close we were and treated Rima like one of the family.

In the fourth or fifth class people had stopped using our names in the village and just said “Rima’s friend” or “Sona’s friend”.

In that area everyone treated each other with respect and valued their neighbours’ traditions. They celebrated Novruz with us and we celebrated Vardavar with them.

The Azerbaijanis who grew up in that region celebrated the festivals slightly differently from how it was done elsewhere, like Baku for instance. At Novruz we had different sweets: not baklava or gogal but kömbə, a kind of sweet bread made with milk. And we had other dishes, such as hədik — a porridge made from five different grains, which was a symbol of fertility.

All the girls in the village, not just the Azerbaijani girls, would get together for the traditional fortune telling with needles. For this, one of the girls had to go out early in the morning to fetch the dinməz suyu [the ‘silent water’] from the well and then bring it back in silence, without talking to anybody she might meet on the way.

After midnight the water would be poured into a dish and the needles would be half wrapped in cotton wool. Then they were dropped from a height into the water. If the needles landed close together, it meant your wish would come true.

In July everyone from round about travelled to the village of Shakhnazar [now Metsavan, Ed.] for Vardavar. That was our favourite summer festival. Every year there was a wonderful colourful fair there. The children bought lots of sweets and the best bit was that you could drench each other with water because that’s the main Vardavar custom. The Azerbaijanis used to call that day vardavar bazari [Vardavar bazaar]. For some it was a festival, for others it meant good business.”

***Makhira also comes from the Lori Valley, from the town of Evlu [now Dzoramut, Ed.], but there were only Azerbaijanis living in her village. This is the story of her childhood in Armenia.

“Every year we took the cattle to oy deresi, the summer pasture in the mountains. We spent the whole summer there. The adults looked after the cows and made cheese and butter for the winter stores, while we children ran around the valley, swam in the river and picked mushrooms.

On one of the mountains, Mount Girri, there were lots of stones with hollows in them that looked like the prints of horses’ hooves. It was said that they were the hoofprints of the horses of Hıdrellez.

Hıdrellez is a festival celebrated by some Turkic people to commemorate the time when two prophets – Khidr and Ilyas – met on earth. The villagers didn’t know all the details so they combined the prophets to create the single, mysterious ‘Hıdrellez’.

The hoofprints of Hıdrellez were considered to be sacred and the custom was for us to take sugar with us. Our parents said a couple of lumps of sugar was enough to honour the place but we, in a fever of pious reverence, stole almost all the sugar there was at home and put a lump in each hoofprint. By the way, back then people usually bought enough sugar to last for a couple of months!”

Until 1989 Azerbaijanis were in the majority in the Amasiya district of Armenia, comprising around 70 per cent of the population.

Vagif was born in the town of Gyullibulag (which means ‘flowering spring’ in Azerbaijani). It is situated one kilometre from the border with Turkey and is now known as Byurakn. One of Vagif’s earliest memories concerns this border.

“When I was a child we sometimes found pieces of paper with fancy Arabic script lying in the road. We would kiss them and copy everything written on them into a special notebook. The pieces of paper themselves we carefully preserved as if they were fragments of the Koran. Later I found out that they were sweet wrappers from Iranian sweets which were occasionally carried over the border from Turkey by the wind!

In that area the groundwater was very close to the surface, so everyone could dig their own well. On May Day (celebrated during Soviet times with picnics and barbeques) people didn’t just look for a suitable spot for the festivities, they would choose a well as the focal point. Someone even used them like a fridge, the water was so cold.”