Young teachers head to remote villages under Armenia’s 'Teach for Future' programme

“Teach for Future of Armenia” programme

Under the “Teach for the Future of Armenia” programme, around 50 young specialists are sent each year to work in remote villages and towns across the country. They are selected from a large pool of applicants who complete a specialised training course. Only after finishing the courses do the top candidates go to Armenian communities where schools face a shortage of teachers.

The programme has operated for more than ten years and has become an official partner of the global educational network Teach for All. This international network of social leaders operates in 36 countries worldwide. Its goal is to improve education quality and enhance living standards within local communities.

Here is how the “Teach for the Future of Armenia” programme works and the achievements it has delivered over the years.

- Private schools gain popularity in Armenia as parents seek alternatives

- Yerevan youth leave city to work in village schools

- Armenian children lead world in sugar consumption, sparking health concerns

- Teacher salary increases: Educational reforms continue in Armenia

‘If I hadn’t applied to programme, I’d probably be sitting in some noisy office in Yerevan right now‘

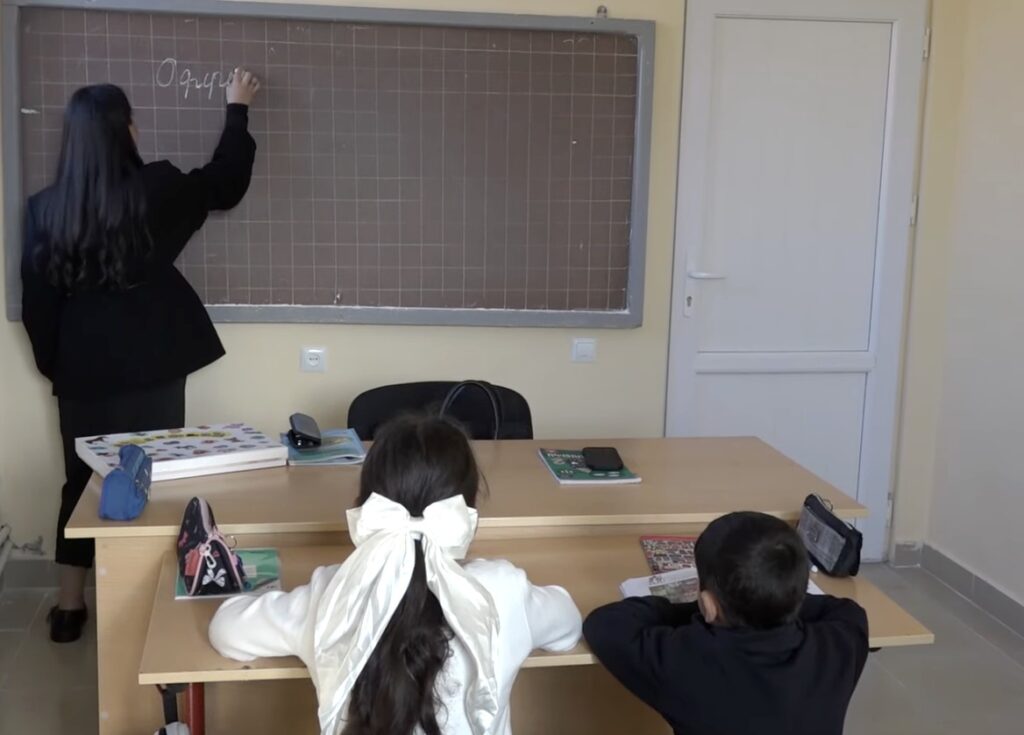

Mané Mkrtchyan, a programmer and information security specialist, is one of the teachers in the 11th cohort of the “Teach for the Future of Armenia” programme. Since September, she has been teaching in the village of Dovegh in Tavush province.

The school in this border village, home to 500 people, had no mathematics teacher. Mané now teaches algebra and geometry to students in grades 6 to 10.

“There are only 57 students in the school. I teach 22 of them. They are engaged, curious, and very smart. From my first day in Dovegh, the community welcomed me warmly. Now, even if I leave the village for a day, neighbours call to ask why the lights in the house are off, where I am, and if everything is okay,” Mané says.

In her fourth year at Yerevan State University, Mané completed the specialised courses of the “Teach for the Future of Armenia” programme. This gave her the opportunity to work at the school in the village of Dovegh.

“At the time, I thought it would be great to apply and take part. I enjoy living away from cities, in a quiet and peaceful environment. If I hadn’t applied to the programme, I’d probably be sitting in some noisy office in Yerevan right now. For me, it is important to work with people, communicate, and be on the same wavelength as them,” Mané Mkrtchyan says.

Engaging recent graduates in educational projects

Arshak Poghosyan, head of the university collaboration programme at “Teach for the Future of Armenia,” says the programme receives 250–300 applications from students each year. Applicants are introduced to the programme’s various projects.

“We pay special attention to involving graduates in our projects. On average, over the past three years, around 700–800 young people have considered moving to the regions. In the end, only 7–8 percent of applicants pass the selection. But the positive aspect is that young people think about relocating, living independently, developing their skills, and achieving financial stability. Here, they receive both the salary paid by the school and the allowance provided by our programme, resulting in a substantial income.

In the first year of the two-year placement, we pay them 200,000 drams ($526) per month, and 100,000 drams ($263) in the second year. This financial support comes from our programme and includes housing. From the second year, our teachers can take the certification exams like other Armenian educators. If they pass successfully, they receive a higher salary from the school itself,” explains Arshak Poghosyan.

‘Children from rural areas have far greater potential‘

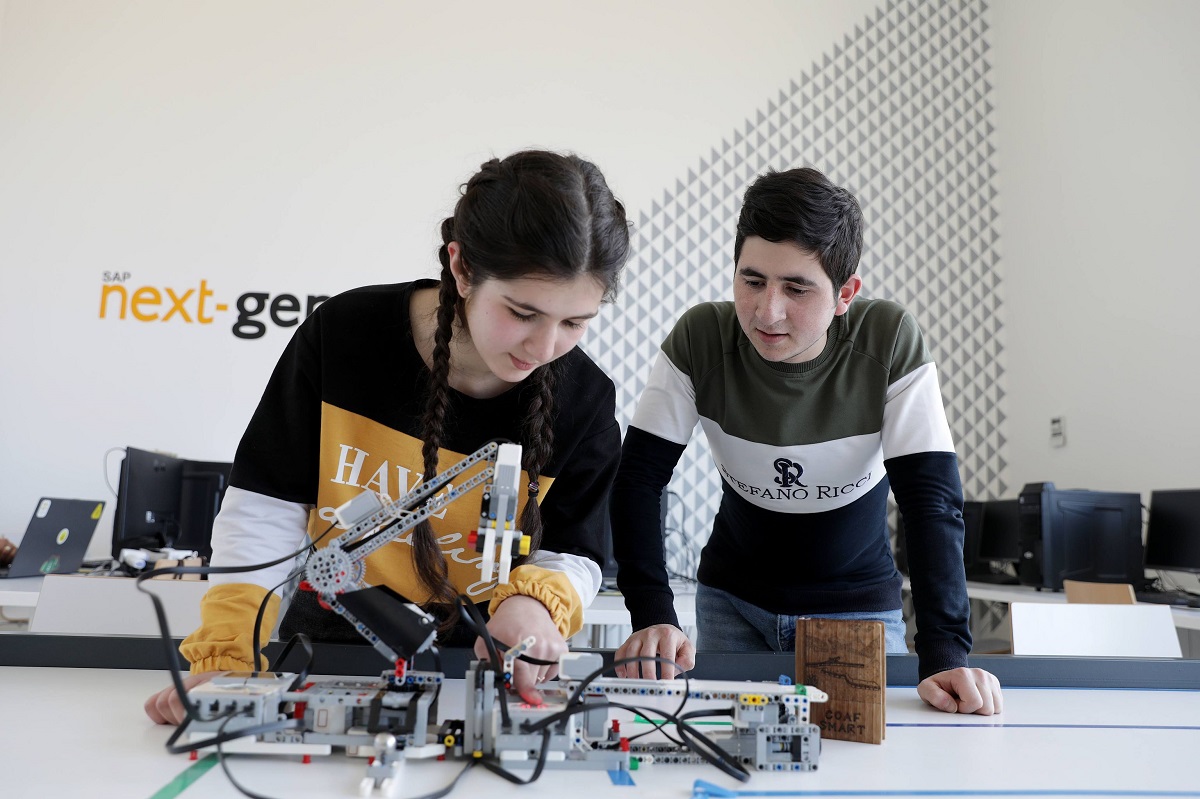

Maria Atanesyan has been teaching for two years at a secondary school in the village of Shamb, Syunik region. She joined the programme in her fourth year at the Pedagogical University. The 23-year-old teaches mathematics, digital literacy, and computer science to students in grades 5–12.

“I wanted to work in a village. I always felt that children in rural areas miss out on many opportunities. There aren’t many music schools or clubs, and not everyone can practice their favourite sports. But I believe they have great potential because they grow up in more natural conditions. You just need to nurture that potential and work with them,” Maria says.

At first, she worried that adapting to village life would be difficult, but it turned out to be much easier than expected.

“My students really helped me. I always engaged with them openly and friendly, even outside of lessons. This two-year programme shapes us as individuals. It gives us confidence, teaches self-organisation, and encourages a balanced lifestyle. You take responsibility for everything, starting with your own decisions. You feel the freedom of choice but learn to consider every step carefully,” the young teacher reflects.

Programme sends not just teachers to villages, but leaders.

Teachers taking part in the “Teach for Armenia’s Future” programme receive leadership training.

Narine Vardanyan, the programme’s manager for leadership development, says the teachers sent to villages are expected not only to teach students but also to “be an inspiring and motivating leader for the entire community.” The programme aims to strengthen local communities. According to Vardanyan, teachers implement various projects in line with their skills and experience.

“A lot depends on the teacher-leaders, so that the community accepts them, trusts them, and believes in them. At the same time, they need to understand everything that exists in the settlement. You can’t arrive in a region acting like a savior. You need to learn from the people there. They have so many wonderful traditions and residents with vast experience. You must identify these and combine your innovative ideas with their knowledge. You need to communicate and negotiate effectively. That’s essential for collaboration.

Clearly, a newcomer isn’t immediately accepted as one of their own. But after two years, when their assignment ends, farewells are almost always emotional. During regional visits, people often ask me how to keep our teachers here,” Narine explains.

Over the past ten years, the programme has trained 450 graduates.

Over ten years, the “Teach for the Future of Armenia” programme has sent 450 teachers to rural areas, where they are known as “ambassadors of new ideas.”

Vardan Partamyan, the program’s promotion director, says the teachers earned this title “for their efforts to tackle inequality in education.” He stresses that real change does not start with grand statements or good intentions:

“Change begins with leadership that emerges and develops in the classroom. When teachers, students, and the community start trusting each other and making decisions together, the system begins to transform—class by class, school by school. This experience has had a significant impact on shaping the education system. Today, we can already see how quickly reforms can advance when they come from within the community, respond to real needs, and are guided by people’s belief that change is possible.”

‘Every school lacks teachers in science and mathematics‘

Vardan Partamyan says the biggest challenge for regional schools is the shortage of science and mathematics teachers, with up to 600 positions left unfilled each year.

“If we look at vacancies, mathematics, computer science, and physical education teachers top the list, followed by physics and chemistry. Various programs aim to address this, but the problem remains. Each year we manage to place 50–60 teachers, covering roughly ten percent of the gap. If 60 mathematics positions remain vacant, it shows the shortage exists across all regions. We try to be flexible and fill as many teaching roles as possible,” explains Arshak Pogosyan, head of the university cooperation program.

About 25% of program teachers specialise in mathematics and computer science. Fewer are assigned to English, Armenian, or history.

“It isn’t easy to find the right specialists, even though we collaborate with all leading Armenian universities. Pedagogical institutions train students professionally, while others, like the mathematics faculty at YSU, produce students who excel in the subject but lack teaching experience. We work with them as well. We also maintain strong links with the Economics University, which provides additional specialists every year,” Pogosyan adds.

Ovik Ovsepyan and Mariam Sargsyan joined the programme this year.

Mariam is a journalist, and Ovik is an economist. Since September, they have moved to the border village of Koti in Tavush province. Mariam teaches Armenian language and literature, while her husband teaches mathematics and geometry.

“We first heard about this programme when it was only two or three years old. Back then, they had already started sending teachers to Artsakh. We saw how these teachers managed to change the life of the community. Thanks to them, the community’s life gained meaning,” Mariam said.

After relocating from Nagorno-Karabakh to Armenia, she noticed an announcement targeting Karabakh natives. They applied in the spring and completed several training stages. The Ministry of Education supervised their training, through which they earned their teaching qualifications. “We are both from Martuni. Life in Yerevan felt alien to us; we missed nature and rural life. That’s how we ended up here,” Mariam added.

Koti school has 200 students. Mariam teaches grades 5–7, and Ovik teaches grades 5, 8, 10, and 11.

“When we arrived, everything reminded us of Artsakh—the local dialect, the nature, the rocks and mountains. We thought, for two years, we’ve returned home. We’ve only been here two months, but it feels like we’ve lived here for years,” Mariam said.

Impact of the programme on the education sector

Arshak Pogosyan, head of the programme’s university cooperation initiative, believes the organisation helps young people develop a strong connection to schools and teaching.

“Sixty to seventy percent of our graduates continue working in education. They take positions as school principals or deputy principals. Even if they do not stay in schools, they find roles in related fields. This shows that during their time in the programme they grow to love working in schools. They start enjoying teaching and remain in the sector. We even have cases where they continue working in the very communities to which we assigned them,” he said.

The effectiveness of the “Teach for the Future of Armenia” programme in education is also reflected in its new initiatives.

“The programme started with 14 participants. Now, ‘Teach for the Future of Armenia’ is just one of our initiatives. We also run the ‘Seroond’ (Generation) programme, a unique system operating at the primary school level. We have a master’s programme in collaboration with Yerevan State University, focused on teacher preparation and training, called ‘Leadership.’ Additionally, we created the ‘Kayts’ (Spark) incubator, where our teachers can develop start-ups and secure funding. We also established a public policy development lab, mostly staffed by our alumni, with a mission to draft and propose regulations and legislation in education,” Pogosyan explains.

“Teach for Future of Armenia” programme