Transit of wheat to Armenia through Azerbaijan: what it means economically and politically

Wheat transit to Armenia via Azerbaijan

In early November 2025, for the first time, 1,048 tonnes of Russian wheat were delivered to Armenia by a 15-car train that passed through the territories of Azerbaijan and Georgia. Following that, on 8 November, about 1,000 tonnes of Kazakh wheat were sent to Yerevan via the same route, also in a 15-car train.

Grain shipped from Kazakhstan is first delivered to Azerbaijan (by rail and across the Caspian Sea), then transported along the Azerbaijani railway to the border station of Beyuk Kesik, from where it passes through Georgian territory and enters Armenia’s railway network.

For the first time in more than 30 years, Armenia has begun importing wheat through Azerbaijani territory, which has been used as a transit corridor.

The article analyses how this transit became possible, what political and logistical factors lie behind it, and what opportunities this corridor could open up for other freight shipments in the future.

Will the trial shipments mark the beginning of regional cooperation?

The terms, toponyms, opinions, and ideas used in this JAMnews article reflect solely the position of the author or the specific community and do not necessarily represent the views of JAMnews or its individual staff members.

Start of transit: new policy

The possibility of new transit became a direct result of political decisions. Azerbaijan lifted long-standing restrictions and agreed to allow commercial cargo to pass through its territory to Armenia.

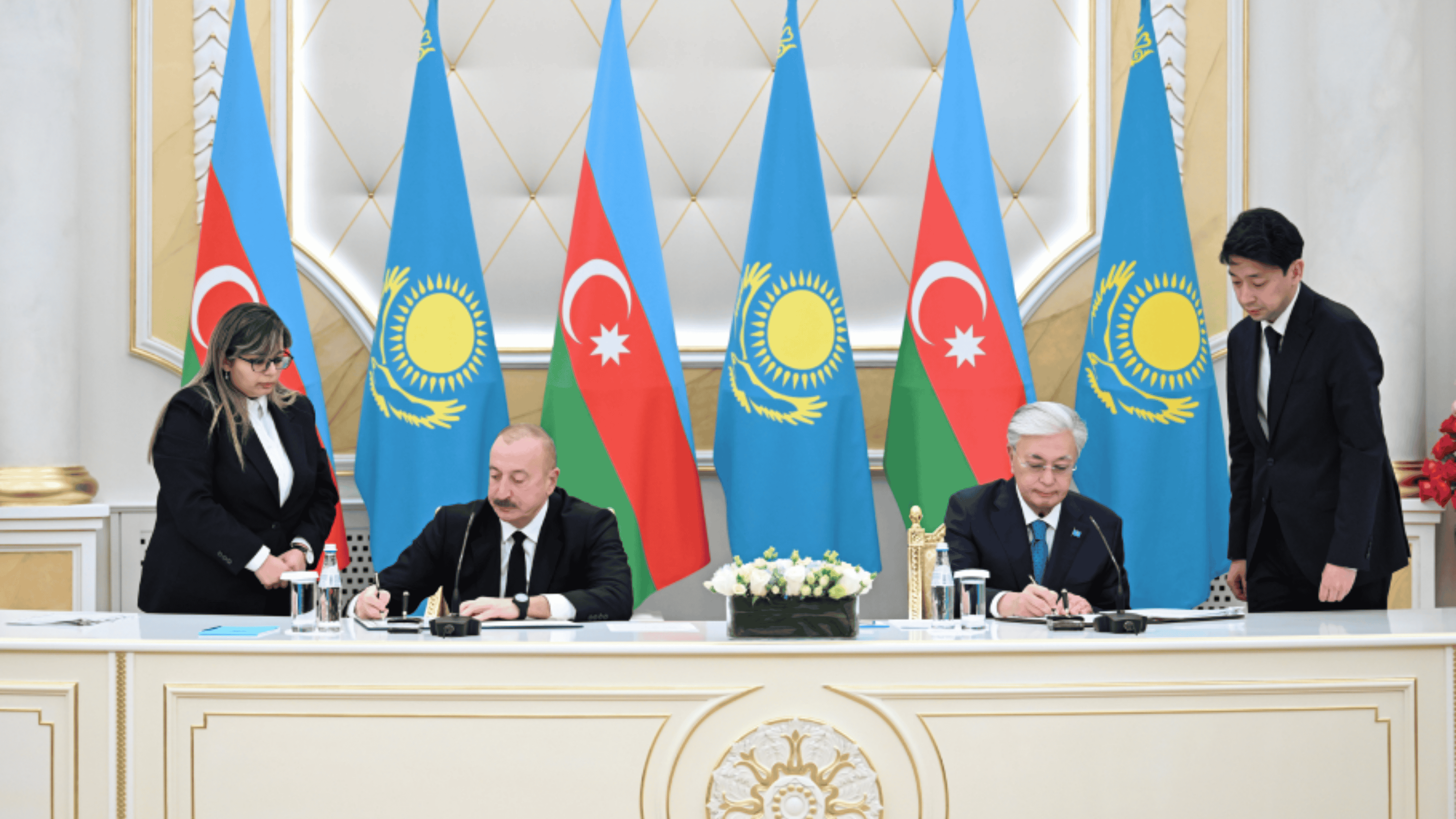

On 21 October, during a meeting with the President of Kazakhstan in Astana, President Ilham Aliyev announced the removal of all bans on the transit of goods from Azerbaijan to Armenia.

Aliyev said that the shipment of Kazakh wheat along this route “shows that peace between Azerbaijan and Armenia exists not only on paper but also in practice.”

The Armenian government also viewed this step as an important gesture towards opening regional communications and strengthening mutual trust.

Direct transport links between Azerbaijan and Armenia had been closed since the late 1980s, and the first wheat trains are seen as a historic event.

Launching the transit required not only political will but also coordinated practical measures. Agreements were reached between the railway authorities of several countries, and the first deliveries confirmed the functionality of the new logistics scheme.

And the first deliveries confirmed the viability of the new logistics scheme.

Long-term supply plans: agreements between Kazakhstan and Armenia

Following the initial trial transits, Kazakhstan and Armenia announced their intention to establish regular wheat trade.

Kazakhstan’s national grain company declared its readiness to supply Armenia with between 15,000 and 20,000 tonnes of grain per month.

As early as October, Kazakhstan signed long-term cooperation agreements with Armenian companies, with the first shipment seen as a pilot stage of this arrangement.

If the deliveries are carried out monthly in the declared volumes, this will amount to 180,000–240,000 tonnes of wheat per year and will cover a significant share of Armenia’s annual demand.

Kazakh officials described the launch of wheat deliveries as an example of “food diplomacy” and stressed that this step marks the beginning of a new stage of economic cooperation in the region.

Armenia’s wheat demand and the impact of new route

Armenia consumes about 350,000–400,000 tonnes of wheat annually, a significant share of which is covered by imports.

For many years, Russia remained the dominant supplier. In 2024, for example, Armenia imported 316,000 tonnes of wheat, more than 99% of which originated from Russia.

The risks stemming from such dependence have become particularly evident in recent years.

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the ongoing war have led to fluctuations in the global grain market, raising concerns in Yerevan about the country’s food security.

The emergence of Kazakhstan as an alternative supplier could increase market competition and help stabilise prices for flour and bread.

In addition, the geographical diversification of routes will make it possible to offset potential disruptions in certain directions — for instance, due to political tensions or export restrictions.

Experts emphasise that this transit represents a strategic step towards “reducing Armenia’s dependence on Russian grain.”

Transporting wheat by rail through Azerbaijani territory is also advantageous from a logistical standpoint.

Until now, cargo from Russia and other northern routes was mainly delivered to Armenia via the mountainous Upper Lars pass and checkpoint in Georgia — a route often disrupted in winter.

The new railway route ensures year-round delivery of large cargo shipments, regardless of weather conditions.

Prospects for expanding route: other types of cargo

The new transit corridor is currently used for transporting wheat. However, both Azerbaijani officials and regional analysts do not rule out that in the future this route could be utilised for other types of cargo as well.

Kazakhstan has already announced its intention to use this corridor for the supply of other goods to the Armenian market.

Thus, if the route proves successful, it could eventually be used by suppliers of animal feed, various fertilisers, as well as metallurgical and chemical industry products.

For Armenia, this could mark a step towards restoring and expanding trade ties with regions that have long remained closed to the country.

If two-way transit develops further, officials in Yerevan do not exclude the possibility of using this corridor to export Armenian products — such as alcoholic beverages, mineral water, and other goods — through Azerbaijani territory to third countries.

Alternative routes: via Georgia and Trump Route

At present, the only fully operational route for transporting goods from Kazakhstan and Russia to Armenia remains the one passing through Georgia.

All wheat trains travel through Azerbaijani territory and then enter Armenia via the Georgian railway network.

This is the “classic” route that has developed over many years. Since the 1990s, Georgia has played a key transit role in Armenia’s foreign trade.

However, in the near future, the region may see the emergence of a new transit corridor — the Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP).

In August 2025, during a meeting in Washington, the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia, with the participation of Donald Trump, reached a preliminary agreement to establish unimpeded transport links between Azerbaijan’s mainland territory and its Nakhchivan exclave through Armenia’s Syunik Province.

If implemented, the project would give Azerbaijan a direct connection from its main territory to Nakhchivan and further to Turkey, while allowing Armenia to benefit from new transit opportunities.

This route could become a shorter and more direct alternative to the existing transit through Georgia, as it would not cross third-country territory.

The process of agreeing on the technical and political details of TRIPP is still ongoing, and no final arrangements have yet been reached.

Therefore, for now and in the foreseeable future, the Georgian route will remain the main transportation channel. Although geographically longer, it remains the only established and practically functioning route agreed upon by all parties.

Project’s success directly depends on maintaining sustainable peace in region

A full peace agreement between Baku and Yerevan has not yet been signed. If the political situation escalates again or incidents occur along the border, the Azerbaijani government may suspend its permission for transit.

This is only a “partial easing of the de facto blockade.” Azerbaijan is accepting cargo destined for Armenia, yet no border crossing points between the two countries have been opened so far.

The absence of an officially delimited border remains a potential source of tension. Until the status of the border is finally defined, the political sensitivity surrounding the transit will persist.

Another risk factor lies in the technical sustainability of the transport operations.

To keep transportation cost-effective, a favourable tariff policy must be developed among the parties.

At present, the transit countries (Azerbaijan and Georgia) apply standard railway tariffs. If shipment volumes increase, long-term tariff agreements will be needed to ensure the route remains competitive.

The resilience of infrastructure is also crucial.

The first deliveries showed that, from a technical perspective, train traffic does not face major obstacles. However, as the number of freight trains grows, it may become necessary to increase the railway network’s throughput capacity.

Therefore, railway operators in all three countries must act in constant coordination.

For now, this transit is seen as an “economic fruit of peace,” but its long-term success will depend on the stability of the political environment and the timely resolution of emerging technical and logistical challenges.