EU and Azerbaijan: human rights values overshadowed by energy geopolitics

European Union and Azerbaijan

In recent years, relations between the European Union and Azerbaijan have seen a notable shift: the focus on human rights and democratic institutions has gradually receded, while energy security and regional geopolitics have taken centre stage. This shift coincides with the harshest phase of domestic repression in the country.

This parallel development has significant implications both for the EU’s claimed normative role and for the emerging new political order in the South Caucasus.

This article is based on data and findings from the 2025 report Neglecting Principles: The Human Rights Crisis in Azerbaijan – The European Union Prioritises Energy and Geopolitics, produced by the Campaign to End Repression in Azerbaijan, an initiative led by human rights defenders and NGOs who have been studying systematic arbitrary arrests in the country for more than twenty years.

Shifting the balance of power: Azerbaijan’s rising influence and Europe’s silence

According to the report, Azerbaijan’s international weight has grown significantly since 2022: control over energy routes, its role as a key transit link between the Black Sea and the Caspian, hosting COP29 in Baku, and the diplomatic image shaped through humanitarian support to Ukraine have all expanded the country’s geopolitical significance.

However, this rise has been accompanied by harsh repression of vital domestic institutions — including the media, NGOs, independent politics, and academic discourse.

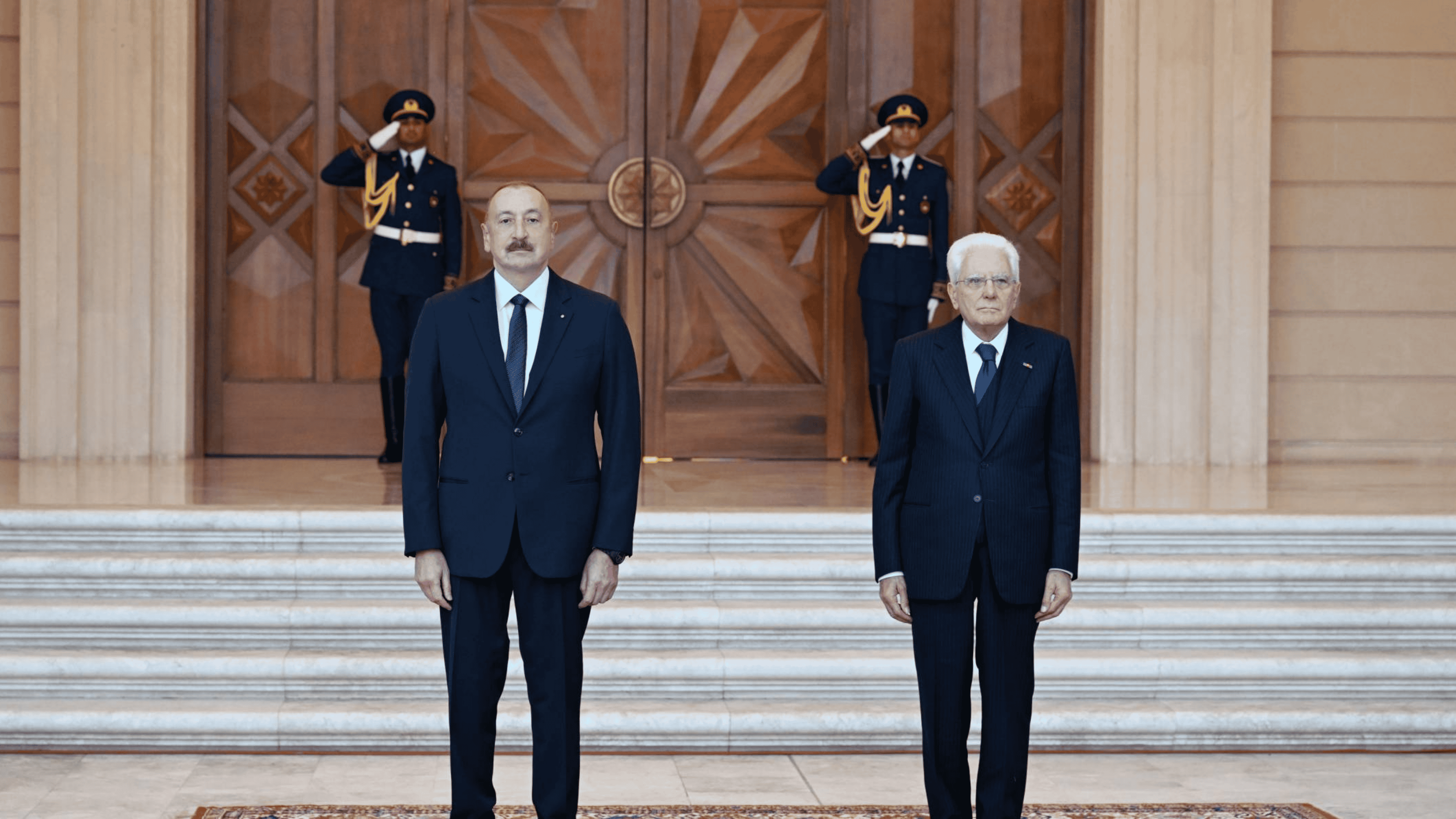

During visits by EU special representatives to Baku, human rights were either not raised at all or reduced to symbolic statements, which in Azerbaijan was interpreted as a signal that authoritarian governance carries few diplomatic costs.

From a values-based partnership to interest-driven cooperation

The 1999 Partnership and Cooperation Agreement, which formed the basis of relations between the two sides, explicitly emphasised the importance of human rights, the rule of law, and the strengthening of democratic institutions. However, analysis of the report shows that since the 2010s, this framework agreement has gradually lost its real influence.

In 2013, by rejecting an Association Agreement, Azerbaijan signalled its unwillingness to accept political conditionality.

Between 2015 and 2018, the two sides shifted to a “modernisation” model, in which relations were built primarily around energy, trade, and infrastructure.

Since 2022, Russia’s war against Ukraine has sharply increased the EU’s need to diversify its energy sources, making cooperation with Baku a geopolitical priority.

Thus, values-based policy has gradually given way to an instrumental approach grounded in pragmatic interests.

The energy factor: the EU’s top priority and a source of tension

After the signing of the 2022 energy memorandum, the focus of bilateral relations shifted to increasing gas exports and expanding the “Southern Gas Corridor” passing through Azerbaijan.

As the report notes:

- The EU is Azerbaijan’s main trading partner, accounting for 63% of the country’s exports;

- Between 2022 and 2024, EU demand for Azerbaijani gas and oil declined, yet this policy was maintained as a political priority;

- At the same time, Azerbaijan’s growing imports of energy from Russia and suspicions of “rebranding” Russian gas for European supply make such cooperation strategically paradoxical.

These developments pose a fundamental question for the EU: does prioritising energy security over normative values ensure long-term stability, or does it, conversely, strengthen authoritarian systems?

A new phase of repression: political prisoners, media crackdown, cross-border persecution

The report notes that Azerbaijan now holds the highest number of political prisoners since independence — more than 400 people. In 2024–2025 alone, the closure of major media outlets, the expulsion of BBC and VOA journalists, and mass arrests of staff at AbzasMedia, Toplum TV, Meydan TV, and other platforms have effectively reduced press freedom to zero.

Repression is not confined to the domestic sphere: surveillance of journalists and human rights defenders abroad, pressure on their family members, and attempts to use Interpol all demonstrate that Baku is extending political control beyond its borders.

Against this backdrop, EU silence carries not only normative risks but also real consequences: the costs of repressive policies are lowered, and mechanisms for public protection are entirely undermined.

Fragmentation within the EU: Parliament takes a hard line against the Commission’s “pragmatism”

According to the report, in 2024–2025 the European Parliament issued strong calls to freeze the energy agreement with Azerbaijan, impose sanctions for human rights violations, and link relations to the release of political prisoners.

However, the European Commission and the European External Action Service did not follow through in practice, continuing energy and trade dialogue in the usual format. This dual approach sends a clear signal to the Azerbaijani authorities: tough statements carry no real political consequences.

Background

The EU’s different approaches to various countries make this contradiction even more apparent. In the cases of Belarus and Georgia, the EU openly condemned repression, imposed sanctions, and provided systematic support to civil society.

In its relations with Azerbaijan, similar tools are not applied, even though the country’s political system is equally authoritarian, and at times even harsher.

This disparity highlights the gap between principle and realpolitik in the EU’s policy in the South Caucasus.

Summary

The report’s conclusions show that the EU’s current policy, on the one hand, provides short-term convenience in energy security, but on the other, contributes to the further closure of Azerbaijan’s domestic political space and undermines the Union’s own value system.

The most critical point is this: if, during a period of deepening repression in Azerbaijan, the EU’s political support remains focused primarily on energy cooperation, it sends a signal not only to Baku but to all authoritarian actors in the region that values are not principled.

This contradiction raises doubts about the long-term stability and democratic development of the entire South Caucasus.

European Union and Azerbaijan