Awaiting end of war in Ukraine: Russia’s intentions in South Caucasus

Russia’s next steps in the South Caucasus

Against the backdrop of the prolonged war in Ukraine and its unpredictable consequences, Russia continues to press geopolitical claims on Armenia. A recent visit to Moscow by Armenian parliament speaker Alen Simonyan, where he met Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov, showed the firmness of Moscow’s position. Lavrov openly said Armenia’s European integration is incompatible with membership in the Moscow-led Eurasian Economic Union.

Despite Simonyan’s assurances that Armenia does not see a need to leave the Eurasian Economic Union, many experts interpreted Lavrov’s words as a warning, and even a threat.

Earlier, Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said Armenia is taking steps to meet EU standards while keeping its EAEU membership. He explained that the country will not leave the Eurasian Economic Union as long as it can combine the two directions. When that becomes impossible, the authorities plan to make a final decision together with the people of Armenia. As the prime minister put it, it “will be dictated by the free expression of the will of the Armenian people.”

Will Russia continue its expansion in the post-Soviet space after the war in Ukraine ends? Will Moscow have enough resources to project power in the South Caucasus, or will the region get a respite from Russian pressure? Here is the view of political analyst Sergey Minasyan.

- Putin’s oil and SOCAR plant: EU sanctions impact Azerbaijan

- London’s new strategy: sanctions on Russia and lifting the Caucasus arms embargo

- Moscow attempting ‘Ivanishvili 2.0’ operation in Armenia, says analyst

- Are Azerbaijani Su-22s bound for Ukraine? Assessing the Daily Express claims

Comment by political analyst Sergey Minasyan, deputy director of the Caucasus Institute

Diplomacy alongside war

“Armed conflicts, including world wars, usually go hand in hand with attempts at settlement, from negotiations to ceasefire initiatives. Their intensity depends on how the sides assess the prospects of the war. Even during the Korean War in the 1950s, diplomatic and mediation efforts developed alongside the fighting.”

In 1945, after Japan’s defeat in the Second World War, Korea was divided into North and South. Japan had ruled the peninsula before that. After the war, the United States and the Soviet Union signed an agreement on joint administration of the country. Several factors led to the Korean War of 1950–1953:

- the division of the country along the 38th parallel after the Second World War,

- the ideological confrontation between the USSR and the US,

- and the desire of leaders in both North and South Korea to unite the peninsula under their control.

In the case of the war in Ukraine, fighting continues largely because both sides believe they can achieve their goals by military means or avoid serious territorial and geostrategic losses.

At the same time, mediators and other involved actors are promoting their own diplomatic and political initiatives. They often combine them with direct involvement in the conflict, as the United States and Ukraine’s European partners are doing.”

Mediation without results

“The new US administration, while continuing to provide Ukraine with military, intelligence and logistical support, is trying to act as an acceptable mediator. However, after more than a year, it has become clear that the conflict has a deep, existential character for the warring sides and for Europe. Attempts to freeze it quickly have failed.

Despite intensified negotiations, including in the UAE, the United States appears to accept the possibility of continued and even intensified fighting. It proceeds from the assumption that the sides have not yet exhausted their military, human and political resources.

A theoretical window for freezing the conflict could open between August and October 2026. That could happen if the sides reach a relative military and political balance, if the financial cost of the war for Europe rises, and if a ceasefire gains domestic political importance for Donald Trump ahead of the midterm congressional elections. For now, however, such prospects remain unlikely.”

Impact on the South Caucasus

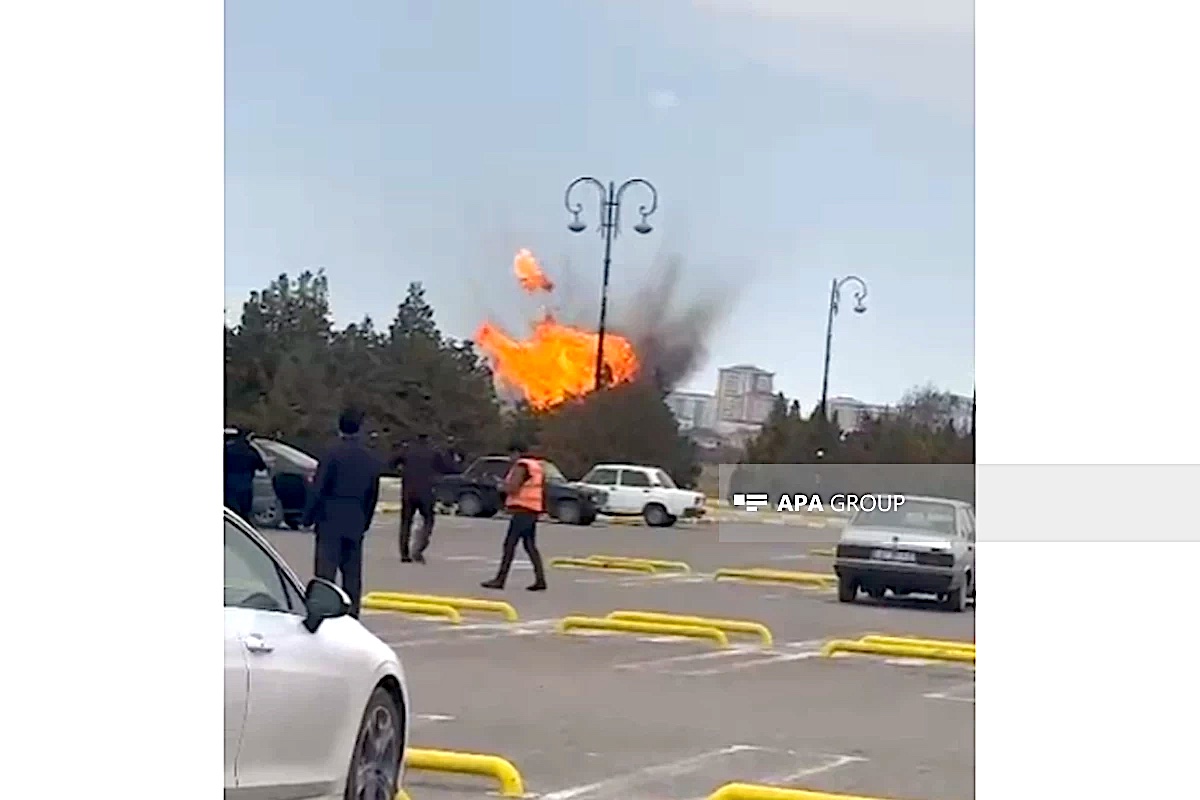

“The war in Ukraine has played, and continues to play, an important role across the post-Soviet space, including in our region. One only needs to recall the deportation of Armenians from Nagorno-Karabakh in 2023 and the events that preceded it, including the gas pipeline sabotage and the passive stance of Russian peacekeepers. By March 2022, it had already become clear that Russia’s war in Ukraine was not unfolding according to the original scenario. That, among other factors, created conditions for escalation in Karabakh and the events of September 2023, when Azerbaijan blocked the region for nine months and then launched military operations, after which almost the entire Armenian population left their homeland.

The prolonged and existential nature of the war in Ukraine, as well as its scale and the depth of involvement by external actors, inevitably affects the South Caucasus.”

Possible scenarios

“Today, it is impossible to speak about the timing of a settlement or a freeze in the conflict. The lack of clarity about the outcome of the war also prevents forecasts about Russia’s future role in the post-Soviet space—whether it will continue an active foreign policy or turn to isolationism.

Possible scenarios remain fundamentally different. They range from an unlikely freeze along the front line to a military collapse of the Ukrainian army and an end to the war on Moscow’s terms. Another scenario would involve an internal political and socio-economic crisis in Russia itself, with major military and political consequences for both Ukraine and the wider post-Soviet region.

Given the existential nature of the conflict and the fact that it represents a military expression of a geopolitical confrontation at least with European countries, Russia is concentrating all its resources on the Ukrainian front—military, financial, human and political.

It remains doubtful whether it will have enough resources to project similar power into the South Caucasus or Central Asia, even if it has the political will to do so.”

Compromise unlikely

“The scale of losses and the significance of the Ukrainian conflict make a freeze extremely difficult. Conflicts of this level never end through compromise. The existential nature of the war in Ukraine—the largest on the European continent since the Second World War in terms of geography, human, material and financial losses—explains the intensity of the confrontation and the willingness of both sides to use all available resources.

A convincing Russian victory would clearly strengthen its political influence and capabilities across the post-Soviet space. A defeat would lead to the opposite result.”

European resources redirected

“It is also important to consider another aspect. The resources of Ukraine’s European partners, which also support Armenia’s European integration, are now largely redirected toward the Ukrainian front.

Aid programmes and grants from the European Union and European countries in the South Caucasus have noticeably declined. Europe has redirected that funding to Ukraine.

For Europe, the geopolitical priority remains the settlement, suspension or freezing of the Ukrainian conflict.”

Russia’s next steps in the South Caucasus

Russia’s next steps in the South Caucasus