All you need to know about Georgian wine boom

Georgian wine success story

Georgian wine is one of the main export goods of Georgia, a visiting card of the country and even a way of life. In recent years, Georgia has been exporting more and more wine. This is definitely a positive development for the economy. However, as it turned out, not everything is so simple – it is a dizzying success that can ultimately do a disservice to the reputation of Georgian wine.

In a special JAMnews project from Georgia, Russia and Ukraine, we talk about how Georgian wine is exported, what the products that go to the main markets for Georgia are, what main producers, consumers and professionals think about them, and what chances does Georgian wine have in competition with wine from other countries.

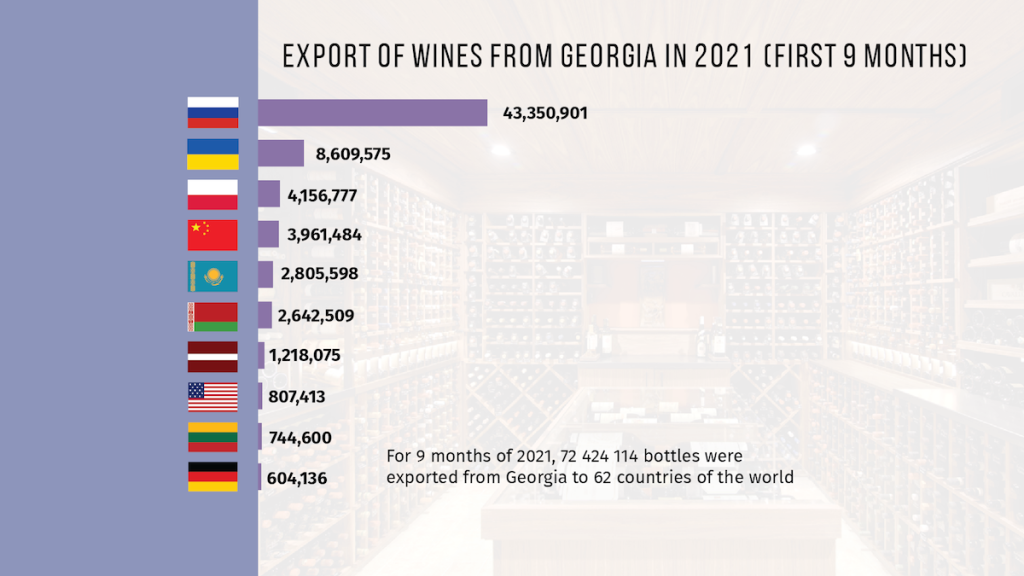

The export of Georgian wine is growing steadily every year. In the nine months of 2021, 374 Georgian companies have already exported over 72 million bottles of wine abroad, and their revenue exceeded $ 168 million.

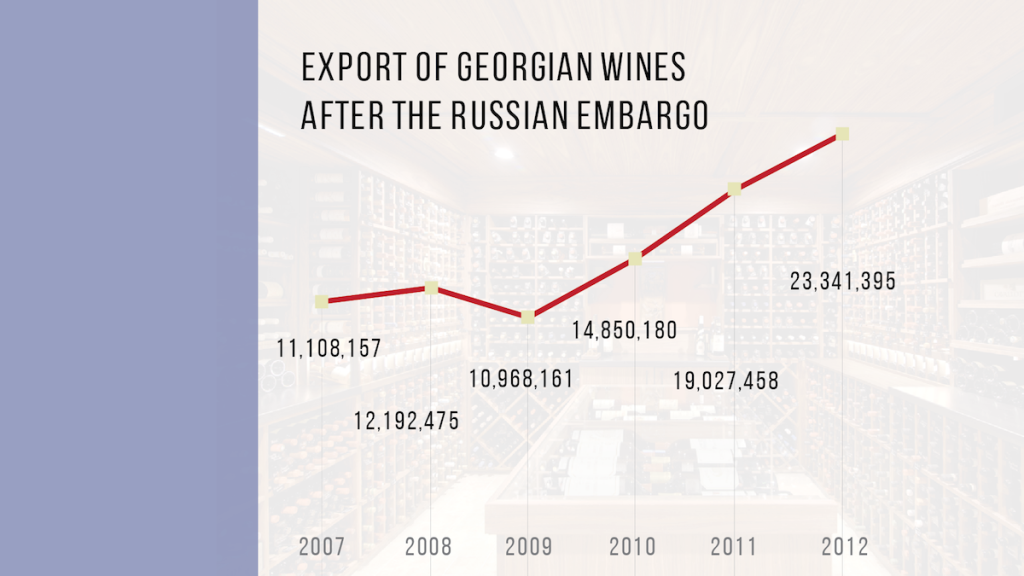

For comparison – 10 years ago for the entire 2011, 19 million bottles were exported, and the revenue was about $ 50 million.

This year Georgian wine was exported to 62 countries of the world. However, more than 43 million, or more than 60% of exports went to one country only – the Russian Federation. The second most important market for Georgian wine was Ukraine, with a share of about 12%.

Takeoff and risk after the lifting of the Russian embargo

Kvareli Wine Cellar is one of the largest wine-making companies in Georgia, which exports 100% of its products.

“Our strategy from the very beginning was to work for export only. The Georgian market is small, and it was more interesting for us to enter the foreign market. However, in the beginning we didn’t have big ambitions”, says Oto Tabatadze, director of the company.

He shows us the company and tells us how the business has grown from 100,000 to five million bottles.

The company was founded in 2008 – that is, two years after Russia imposed a ban on the import of wines from Georgia amid worsening of relations between the countries. Accordingly, the first export markets of the company were Belarus and Ukraine.

Since 2013, after the opening of the Russian market for Georgian products, the export of wine from Kvarelsky Cellar in the first year has tripled: “Before that, we had a maximum of 400,000 bottles, but in 2013 we exported 1,200,000″, Says Oto Tabatadze.

Since then, Kvarelsky Cellar, like most large companies, has supplied the largest amount of wine to Russia – today it accounts for about 65% of the company’s sales. 10% each fall on Belarus and Poland, and the remaining 15 % – in Kazakhstan, Ukraine, Israel, the United States and Turkmenistan.

Like all wine-making companies exporting wine to Russia, Kvareli Cellar also realizes the risk of dependence on an unstable and unpredictable market:

“We understand that this market can be closed at any time, because this country does not obey any logic and decisions are made there for political purposes. We are trying to reduce the share of export to Russia as much as possible and increase penetration to any other market at its expense”, says Oto Tabatadze.

According to him, the best guarantee of stability is the EU market, and the company spares no effort to establish itself in other markets and does not refuse small orders: “With many companies, we started with 500-600 bottles and grew from there”.

The director of Kvareli Cellar explains that companies dependent on Russia “do not have a sense of long-term development, stability and cannot make long-term investments”.

Until 2006, the export of Georgian wines was almost entirely, more than 90%, dependent on the Russian market. For example, in 2005 about 57 million bottles of wine were exported from Georgia, of which more than 52 million – to Russia.

In 2006, Russia imposed an embargo on Georgia. Consequently, wine exports fell sharply in the first year, and exports fell from over 57 million bottles to 11 million in 2007.

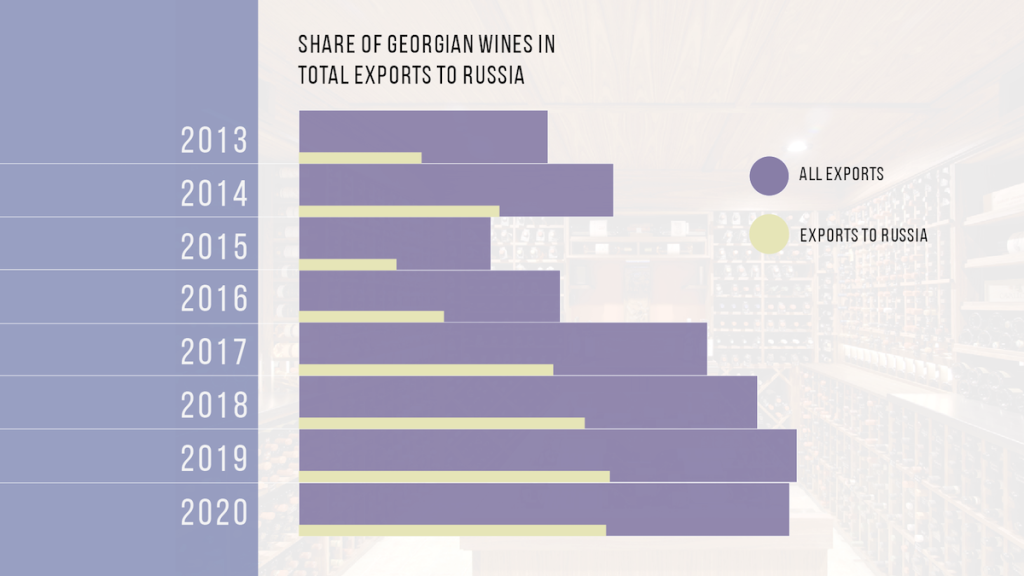

Since 2013, after the opening of the Russian market, wine exports have grown steadily over the past eight years. As a result, the largest amount of produced wine is still supplied to Russia.

“Of course, the opening of the Russian market has played a good role for this sector. In quantitative terms, exports have increased. However, we believe that overdependence on one particular market is bad. Moreover, this market is unstable”, says Levan Mukhuzla, head of the National Wine Agency.

According to him, dependence on the Russian market has historical prerequisites. Since the 19th century, when the industrialization of Georgian winemaking began, Russia has naturally become the main sales market. In Soviet times, there was no question of exporting to the West.

“Of course, all this affected Georgian wine recognition. In fact, we can say that only since 2013, when the State Wine Agency launched a state program to promote Georgian wine, its recognition in modern markets began to grow”.

In 2020, the non-governmental organization Transparency International assessed the danger of dependence of the Georgian economy on the Russian market. The report, published by the organization, says that the high dependence of Georgian wine exports on the Russian market is a serious problem from the point of view of Georgia’s economic security and carries political risks.

Economist Zviad Khorguashvili says that the same problem can be observed in regards to other products – Russia is still one of the three main trading partners of Georgia:

“We are still exploring a cheap market. A normal developed country cannot prefer the Russian market to the European Union as the purchasing power of the EU is about seven times higher than that of Russia”.

Despite its eight-thousand-year history, Georgian wine is not very known in the world. The chairman of the National Wine Agency says a stable and targeted marketing campaign is needed to establish itself in Western markets. Within the framework of the state program in this direction, only the so-called strategic markets – Europe, USA, China are being focused on and nothing from the budget is spent on the countries of the former USSR – this is the state policy.

Market diversification is the only solution

Zviad Khorguashvili believes that the only way out is to diversify the market. He says that production in the country should increase and the Georgian market should be able to meet the needs of rich countries: “This, first of all, requires investment. The economic and political environment in the country is such that investments are being reduced more and more”.

The National Wine Agency also sees market diversification as the only solution:

“There are companies, I would say, exemplary companies that fully understand the instability of the Russian market. Although their products are in great demand in Russia, the share of their supplies to this market does not exceed 30%. I would like others to imitate them”, says Levan Mukhuzla.

Kindzmarauli Corporation is one of the companies with a diversified market. The company has been exporting since 1996 and exports a total of two million bottles of wine to 22 countries around the world. Russia’s share is less than 3%.

“People smarter than me said that you can’t go into the same river twice. This is why we are a little careful today”, says Nugzar Ksovreli, the company’s CEO, recalling the pre-embargo period when they were more dependent on Russia.

“Our marketing and operations are focused on much more stable markets. Today we supply the largest amount of wine to China, Ukraine is in second place, and Germany is in third place”.

The Kindzmarauli Corporation began its presence in China in 2013–2014, and now almost all types of wines are represented on this market:

“The price segment is quite high. There is a demand for more expensive premium wines. These include red aged wines. This is an interesting market in the sense that consumers are well aware of this product”, says Nugzar Ksovreli.

Supply and demand – what goes for mass export

Rkatsiteli, Kakheti Mtsvane, Tsinandali, Saperavi, Mukuzani, Alazani Valley, Kindzmarauli, Khvanchkara, Tvishi, Tsolikauri, Ojaleshi – this is an incomplete list of wines exported by “Kvareli Cellar”. Most of all, the company produces semi-sweet red wines.

“We have both wine designed for mass demand and reserve wines from qvevri (a large earthen jug buried in the ground in which the wine is aged). Of course, their price is much higher [up to $15]. Such wines are more successfully sold in Europe and America than in the CIS countries”, says Oto Tabatadze.

According to him, this is due to the conscientiousness of the consumer, and Georgian wine should not be expensive for consumers in Russia, Belarus, Ukraine or other post-Soviet countries:

“The main demand is for semi-sweet wines: Kindzmarauli, which costs about three dollars, and the red semi-sweet Alazani Valley, at a price of 1.9-2 dollars”.

According to the chairman of the National Wine Agency, the demand for sweet and semi-sweet wines in post-Soviet countries is determined by two factors: income and purchasing power, that is, the economic situation of the population, and the second is the culture of wine consumption.

“Historically, in Northern and Eastern Europe, mainly other alcoholic beverages have been consumed. Wine culture appeared relatively late, and ordinary consumers prefer semi-sweet and sweet wines”, says Levan Mukhuzla.

According to him, in such countries Georgia is traditionally known for Kindzmarauli and Khvanchkara wines – “these are semi-legendary names, and there is nothing wrong with that”.

According to the National Wine Agency, last year the largest export volume (18,676,195 bottles) fell on Kindzmarauli, a semi-sweet red wine with a protected designation of origin.

Levan Mukhuzla says the picture in Western markets is completely different: “Where we are establishing ourselves now, for example, in the United States, mainly qvevri or red dry wines are sold”.

But what about the quality?

“Millions of bottles sold do not mean good wine,” says Levan Sebiskveradze, a sommelier and journalist who has covered wine-related topics for over 20 years. He believes that focusing on the Russian market will not be a guarantee of success for Georgian wine, because this market is focused on low-quality and cheap wine.

“Russia is a huge hole into which any amount of wine can be poured. We cannot fill this hole. Or, if we fill it, what are we going to do? Our quality and image will suffer, and many people will think that Georgian wine is something that is sold for three dollars”.

According to him, Georgian wine is something more – more expensive, high-quality, with traditions that go beyond what is now mass-produced and exported.

“Our business is qvevri wine, expensive wine, not some low quality, mass produced wine. Unfortunately, there is no other way to describe those wines”.

The National Wine Agency claims that “if anything is developing today, it is family cellars that create a unique product”.

Levan Mukhuzla says that if 50 wineries were registered in 2013, now there are about 1,500 of them:

“Where we were not known at all, we entered with unique Qvevri wines or dry red wines”.

“This is two-three percent of winemaking in Georgia”, explains Levan Sebiskveradze. He believes that the state is not interested in the real development of the wine industry:

“Winemaking is remembered during elections. They take money from the budget and throw it away – this is called subsidizing the grape harvest. Big companies, big wineries make big bucks. This adds nothing to Georgian winemaking. This money was wasted”, says Sebiskveradze.

Since 2008, the state has annually spent millions of laris to subsidize the harvest. This year, a few months before the elections, 100 million lari [about $ 31 million] were allocated from the budget. From this amount, the state partially compensated winemakers for the costs of purchasing grapes from peasants.

The chairman of the National Wine Agency does not deny that this is only profitable for large companies, and says that “if there is a subsidy, whoever buys more grapes will win anyway”.

According to him, the state plans to stop subsidizing grapes in the future: “It is more correct and justified to create such a stable and self-sufficient sector so that there is no longer a need for subsidies”.

Levan Sebiskveradze believes that if the state really wants to help the development of the wine industry, the millions allocated for subsidies should be spent on much better things in a completely different direction:

“I think that state support will be useful if it helps winemakers to expand their knowledge, finance their education, help their financially – for example, buy qvevri. To finance the school of qvevri making, to preserve and develop this industry”.

Twins Wine Cellar plans to start production of qvevri in the Kakheti region. The founders of the company, twin brothers Gia and Gela Gamtkitsulashvili, own a small cellar in the village of Napareuli and produce only expensive wines.

“Our wine is sold in small quantities, but this wine is made from qvevri, hand made, and it is expensive” , explains Gia Gamtkitsulashvili. Because of this, it is still difficult to expand production, but they have ambitious plans.

The first wine was bottled here from qvevri in 2006. Today, 50% of production is exported at up to $ 25 a bottle.

“In 2009, we were the first to export qvevri wine to Japan. Then there were such markets as Russia, China, Sweden, Great Britain, Germany, USA”, says Gia Gamtkitsulashvili.

According to him, they are constantly looking for new markets. The demand for their wines is growing more and more, but he also notes that “the unique properties of qvevri wine are not well understood abroad and a lot of work needs to be done”.

Russia – the legend of Georgian wine

The rapid growth in the supply of Georgian wine to Russia began immediately after the lifting of the import ban in 2013.

Georgia’s exported wine quickly took the third place in Russia, second only to Italy and Spain and ahead of France. Such data was given to JAMnews by Alexander Stavtsev, vice president of the Russian Association of Retail Market Experts, head of the WineRetail information project.

In 2020, supplies fell by 7%, but in 2021, imports from Georgia went up again.

According to Russian experts, there are two reasons for such popularity of Georgian products. First of all, this is due to the fact that during the Soviet Union Georgian wines were considered the best and many representatives of the older generation continue to think so.

And the second reason is tourism.

“In Russia they don’t drink the wine, they drink the legend. Georgia has become an important tourist destination and people coming from Georgia, including young people, want to drink these wines, because they represent Georgia. Even in spite of the quality. Georgia is a big brand and a big myth in the Russian”, says Stavtsev.

However, the massive import from Georgia, according to the expert, is not good for quality – and it can’t go on like this forever.

“Georgia is well represented now, but sooner or later there will be an alternative … The market fluctuates, and at some point the bubble of semi-sweet wine from Georgia will burst”, says Stavtsev.

Another expert, Artur Sargsyan, head of the Union of Sommeliers and Experts of Russia, who himself hails from Georgi, also shares this opinion:

“Georgia occupies one of the most significant places in the Russian market, but this will not last long. The competition is colossal here“, Sargsyan says.

Georgian producers abuse the fact that Russia “digests everything”, and mainly supply very low-quality cheap wine, which in other countries would hardly be sold in such quantities, the expert said.

“It’s a shame that Russia for the majority of Georgian manufacturers is a kind of place where whatever you send will be sold. But the country’s image suffers from this”.

According to Sargsyan, protective tasting commissions for imports are already being created in Russia, which will screen out wines of inadequate quality. This means that there is a risk of tightening the rules for wines that will be supplied to Russia.

Is Georgia represented in Russia in the segment of higher quality, expensive wines? Russian experts say that it is not.

“If Georgia wants to compete here, it will have a hard time. European countries and Russia itself have marketing programs to promote their wines on the Russian market, while Georgia, as a country, does not invest in this”, says Alexander Stavtsev.

According to him, expensive high-quality wine is also produced in Georgia, but it will be difficult for producers to sell it to Russia without appropriate support. No one in Russia is involved in promoting high-quality Georgian wine – neither in marketing campaigns, nor in the appropriate bureaucratic procedures.

Accordingly, “Georgia in Russia is losing a qualified and worthy consumer”.

“The Russian market is very large, and when we talk about premium or mid-range wines, Georgia is not here, it is in a very low segment. The Georgian government needs to pay attention to this, it is possible that such disrespectful attitude towards consumers can lead to serious consequences for the economy”, says Artur Sargsyan.

Ukraine – there is plenty to choose from

Ukraine is the second most important Georgian wine market. Unlike the Russian market, this market is more than friendly, and here Georgian products are always welcome, and producers, in the foreseeable future, will not face any political risks and dangers of losing this market overnight.

As a post-Soviet country, the Ukrainian market has a lot in common with the Russian one – in particular, the range of Georgian wine, which is in greatest demand here. As in Russia, these are inexpensive semi-sweet wines, conventionally called “Alazani Valley”.

Sergey Sinchenko, the commercial director of Shevchenko, one of the ten largest wine importers in the country, says that the company has been steadily increasing imports of Georgian wines over the past two years, despite the pandemic.

There are dry wines among them, but the main share is semi-sweet wines. Sinchenko explains this by a historical peculiarity.

“This is still the legacy of the USSR, when there was nothing to choose from. And from what was available, Georgian wine was the best, the premium. We have about 600 wines in our portfolio. But my mom, who is 65 years old, asks to bring her “Kindzmarauli”. And there are a lot of such people”.

According to him, winemaking in Georgia has been developing in the right direction lately, there are more dry wines, wines from qvevri, from authentic grape varieties – Kisi, Khikhvi. Premium wines appear and take their place in the market. However, the main sales are the fault of the budget price segment.

Alexander Kotov, sommelier of the Alkomag chain of stores and the Vinnik restaurant, speaking of Georgian wine, lists the names of Georgian wine regions and settlements that not every citizen of Georgia has heard of.

He says with regret that with such richness, quality and variety, the flagship of sales of all importers is a semi-sweet red or white wine, “which does not develop the consumer, his taste, and the consumer is marking”. According to him, because of this, Georgian wine is treated like “something Soviet”, for which the consumer is not ready to pay more than 300 hryvnia [about $ 11].

“We are trying to develop it, we conduct tastings, dinners, many winemakers try the real Tsinandali and Kisi and are surprised that this is Georgian, because they did not expect this from Georgia”, says Kotov .

The most popular Georgian wines in Ukraine harm the image of Georgian winemaking, which, in the long run, may affect their position on the market. Vitaliy Kovach, who is a member of the Italian sommelier association and the founder of the sommelier school in Ukraine thinks so too:

“For example, I would recommend Georgian winemaking to work on its image, because it is quite easy to find an alternative (to mass Georgian wines). Relations between countries and nations are still working here. Georgian winemaking is not doing enough work in the market of our country”.

However, in Ukraine, Georgian wine is also known from the other side. Zorik Umansky is a famous sommelier in Ukraine, who is responsible for the sale of wine and spirits in the GoodWine chain of stores. This network contains only premium wines of the highest quality from around the world.

There is a corner for Georgian wines here. According to Umansky, up to 40 titles from Georgia are represented in GoodWine.

“The top Georgian wines, which are the pride of Georgian winemaking and have changed its image in the world, are not so easy to get. And it’s not easy to sell them”, says Umansky. However, according to him, the company sells wine not only for profit, but also for pleasure.

According to him, Georgian wines compete very successfully in the segment of small, expensive producers of orange and dry reds, as well as organic and natural wines.

But, according to him, often Georgian producers of even the highest quality wines lack stability – not everyone succeeds in maintaining high quality from harvest to harvest.

Experts and entrepreneurs from Ukraine believe that Georgian winemakers still need to work a lot to improve the quality of their products, studying the experience of successful European producers.

Georgia is the birthplace of wines, which are called “orange” or “amber” for which in recent years there has been a huge demand all across the world. However, experts say that the championship of Georgia in “orange” wines was intercepted by producers from Italy, Slovenia and other countries.

The consumption of wines and the wine market of Ukraine is growing steadily, drinking wine is becoming fashionable among the middle class. For successful promotion in this market, Georgian producers should also take into account how the tastes of consumers are changing and what the youth prefers.

“It should be said that you don’t only have Alazani Valley, there are dry and other wines too. When a consumer meets wine not for five, but for 10 euros, he begins to compare it with European wine. We must fight for this category – with Italy, France. We must say: “When we were making wine, when the French were still climbing trees”. With orange wine, the Georgians missed the chance to tell that it was not “orange”, but Kakhetian wine, it was necessary to talk about it loudly. The new generation, which will consume wine in five to ten years, should know about this”, Vitaliy Kovach advises.

“Young people are prefer dry and increasingly bio or natural, everything related to proper consumption and a healthy lifestyle” , says Zorik Umansky.

Experts also advise to pay attention to the problem of competition from wines produced in Ukraine, but with Georgian names. It is legal if the wine contains at least some of the Georgian wine material. But such wines cost two times cheaper than real Georgian ones.

Sergei Sinchenko argues that the Georgian state should pay more attention to the protection of its local names. According to him, precisely because of this problem, real Chilean wines almost disappeared from the Ukrainian market.

“In addition, the support of the state in the promotion is important. France, Italy, Portugal are actively pursuing public policy and issuing grants. Producers come, give an opportunity to taste, look for importers. This process will spur demand for better quality wine”, says Sinchenko.

Zorik Umansky believes that it is the popularity of Georgian wines that hinders the promotion of high-quality Georgian wine in Ukraine:

“In Ukraine, the problem is that Georgian winemaking has a negative trail of the Soviet period. Imagine the success of Georgian wine in Great Britain, Scandinavia, Japan! There they literally sweep it away and everyone buys it. Because everything is there from scratch”.

“Georgia is moving in the right direction and doing the right thing. Georgia has many prospects – unique varieties, historical experience, they love wine, wine is a way of life there. These things will bring results”, Sergei Sinchenko is sure.

In addition, Georgian wine in Ukraine has a huge “head start” – Georgian cuisine. In Kiev, Georgian restaurants can be found at every corner and Georgian wine is the most logical addition to Georgian dishes.