How Moldova managed to involve emigrants in elections and can Georgia do the same?

Moldova and Georgia: emigrant voting

Citizens living outside Georgia have been urging the authorities for over six months to expand their opportunities to participate in elections. Representatives from the opposition and the non-governmental sector see two potential solutions:

- Abandon the remote voting mechanism

- Open new polling stations abroad

The government deems both solutions unfeasible.

The first option is rejected by the Georgian Dream party due to cybersecurity issues, while in the second case, representatives of the ruling party argue that adding polling stations abroad faces obstacles such as mobilizing commission members, opening new consulates, and a lack of adequate resources. Specifically, Beka Odisharia, Chairman of the Committee on Diaspora Affairs, has repeatedly explained that even the entire budget of Georgia would not be sufficient for new polling stations abroad.

However, Georgia is not the only country holding elections for its over one million expatriates abroad. One such country is Moldova, whose example will be examined in the article.

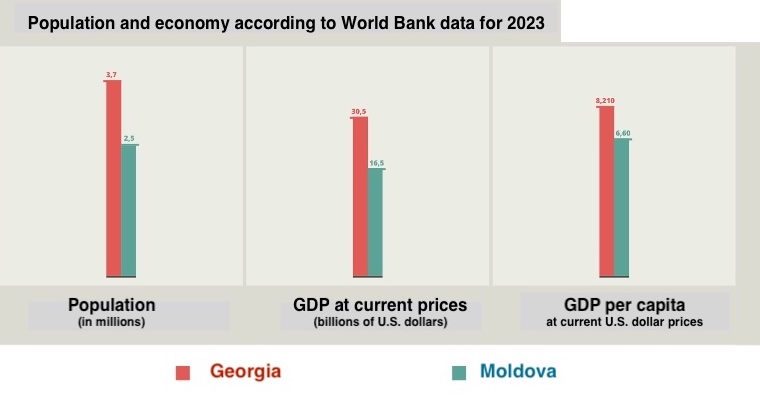

The existing financial resources and the number of expatriates allow for a comparison between the conduct of elections for the diaspora in Moldova and Georgia. In particular, according to World Bank data, the financial resources of Georgia and Moldova are comparable.

According to the Moldovan Ministry of Foreign Affairs and European Integration (MFAEI), the number of citizens living abroad ranges from 1.11 million to 1.25 million.

Of these, 263,117 emigrants participated in the 2020 elections, and 212,434 in the 2021 elections.

In 2020, Moldova spent 9,630,000 Moldovan lei on organizing elections for the diaspora, equivalent to 1,512,275 lari at the current exchange rate (approximately $555,000). Compared to the amount allocated by Georgia’s Central Election Commission for this year’s elections, this represents 0.883 percent of the CEC’s budget for the year.

For the 2020 elections, Georgia opened 57 polling stations in 39 countries. Later, three polling stations in Azerbaijan and two in Greece were closed. In the end, 52 polling stations remained open in 38 countries.

Georgia does not have precise data on the number of emigrants living worldwide. However, according to the UN, there were 850,000 emigrants from Georgia in 2019. Various unofficial sources suggest this number exceeds one million. Members of the ruling party “Georgian Dream” claim there are between 1.5 and 2 million Georgians abroad.

In the 2020 elections, the total number of voters abroad was 66,217, with 12,247 casting their votes. Of these, 162 ballots were declared invalid.

Regarding the establishment of polling stations abroad, the president of Georgia, Salome Zourabichvili, is also working with the non-governmental sector. Zourabichvili believes that expanding opportunities for citizens living abroad to participate in elections is not impossible if there is a genuine will to do so. She cites Moldova as an example:

“Opening polling stations abroad is quite feasible, as we have a close example. Moldova conducted elections and opened 150 polling stations [in 2021]. If Moldova could do it, despite many complaints we might have, we might be able to do it as well. Why do we say we lack resources?” said president Salome Zourabichvili on March 29.

As for the position of the Central Election Commission, its Chairman Giorgi Kaladze clarified in a conversation with Zurab Japaridze, the head of the opposition party “Girchi – More Freedom,” that financial resources are not an obstacle to opening polling stations abroad. If “there are appropriate conditions and legal grounds,” the Central Election Commission “will not hinder the conduct of elections abroad” in the interest of the state.

When discussing obstacles to opening polling stations for the diaspora, the authorities mention legal barriers that allegedly create financial impediments. In particular, representatives of the “Georgian Dream” claim that opening a polling station is only possible in consulates or special diplomatic missions, and additional openings are associated with millions of lari. However, this position is not shared by opposition representatives and the non-governmental sector.

“There is no explicit provision in the legislation that polling stations must be located in consulates or diplomatic missions. It is possible to rent a space and agree with a specific country to use that space for electoral purposes for a certain period. Such a space would be considered a diplomatic representation of Georgia during the rental period,” explains Ketevan Barbakadze, a lawyer for the political party “Droa.”

The political parties “Droa” and “Girchi – More Freedom” have launched a campaign to advocate for the opening of additional polling stations abroad, titled “A Ballot Box in Your City.” So far, they have gathered 2,710 signatures across 35 cities worldwide and submitted a request to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs to open more voting locations in these areas. In total, they are collecting signatures in 90 cities.

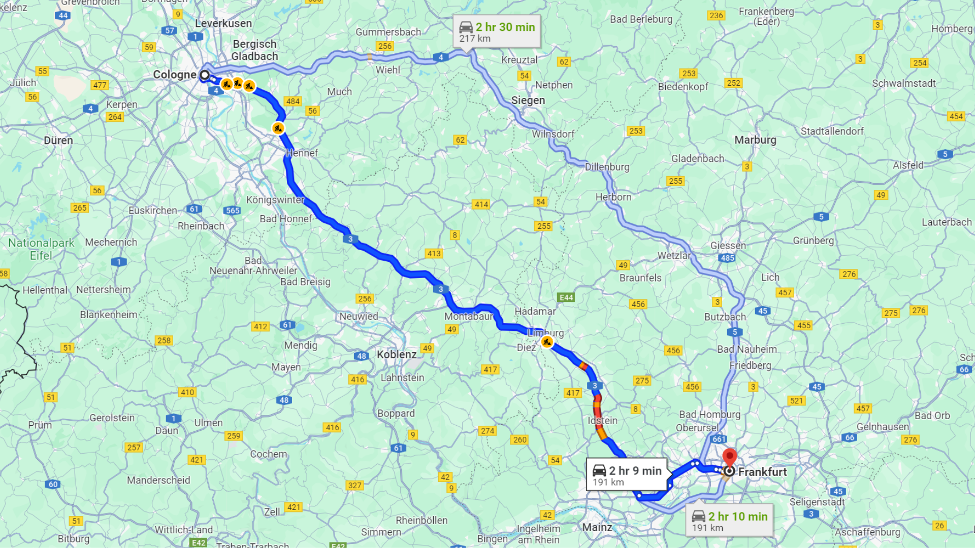

JAMnews spoke with one such emigrant, Sopho Kalatozishvili, who collected 147 signatures and sent a request to the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. Living in Cologne, Germany, she travels 217 kilometers to Frankfurt every election to cast her vote.

According to Kalatozishvili, while her work schedule allows her to make the trip, many emigrants around her find it challenging to make the roughly eight-hour round trip necessary to vote:

“Driving or taking a high-speed train, which is quite expensive, takes about two hours. By regional train with transfers, it can take four or more hours,” she explains.

Giorgi Moniava, a legal expert on fair elections, emphasizes that voting is a fundamental right for every citizen, and the state should not impose additional barriers:

“Elections are a primary constitutional right for Georgian citizens, and many, despite their strong desire, are unable to cast their vote. This is a violation of their constitutional rights and an effective limitation.

In practice, Georgian citizens living abroad are in an unequal position compared to those residing within the country. The state is obligated to provide equal rights to all citizens and must address these issues, ensuring that every citizen has an equal opportunity to exercise their constitutional rights, including voting,” Moniava told JAMnews.

Ketevan Barbakadze also highlights the importance of removing state-imposed obstacles and references Moldova as an example:

“The Moldovan state made all necessary concessions to ensure emigrants could vote, which led to an increase in the number of polling stations,” she explains.

During Moldova’s presidential elections, the diaspora’s votes played a decisive role in the victory of the pro-European candidate Maia Sandu.