Georgian Dream files complaint against Pirveli and Formula TV channels over terms like "oligarch’s MP"

Georgian Dream’s lawsuits against Pirveli and Formula

Terms such as “illegitimate parliament,” “so-called parliamentary speaker,” “oligarch’s MP,” and “regime’s city court” have become the basis of a complaint filed by the ruling Georgian Dream party with the national communications commission against the popular opposition channels Formula and TV Pirveli.

Lawyer Tornike Mighineishvili stated that the channels are being accused of violating regulatory provisions of the broadcasting law, which was amended in April 2025. They now face the threat of heavy fines and/or broadcast restrictions.

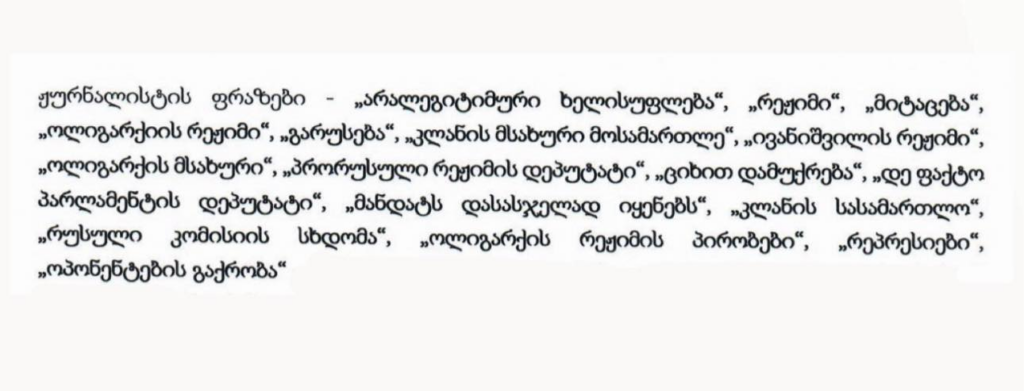

Below is a screenshot of the complaint listing in detail the terms that Georgian Dream deems unlawful and subject to prohibition:

- “illegitimate parliament”

- “regime”, “abduction of people”

- “oligarchic regime”

- “Russification”

- “clans in the judiciary”

- “Ivanishvili regime”

- “servant of the regime”

- “MP of the pro-Russian regime”

- “threats of imprisonment”

- “de facto member of parliament”

- “using a mandate for punishment”

- “clan-based justice”

- “meeting of the Russian commission”

- “conditions of an oligarchic regime”

- “repressions”

- “elimination of opponents”

“This marks the beginning of yet another wave of repression against critical media. The TV channels face the threat of multiple fines and financial sanctions, creating a real risk of their broadcasting being suspended. The complaint will be publicly reviewed by the regulatory commission on 5 June,” the lawyer wrote.

The lawsuit includes excerpts and fragments from news broadcasts and the TV channels’ social media posts, in which the outlets highlighted the political bias of Georgian Dream’s parliamentary majority, as well as of various officials and institutions.

However, Georgian Dream argues that by using such expressions, the TV stations violated the Broadcasting Law, particularly Articles 54, 59¹, and 76.

Particular ire was clearly provoked by the references to the Georgian Dream government as a “regime,” as well as by mentions of Bidzina Ivanishvili—the billionaire and honorary party chairman often referred to as Georgia’s “shadow ruler.” His name, along with the word “regime” in various contexts (“prisoner of the regime,” “representative of the regime,” etc.), appears repeatedly throughout the complaint.

- Georgia: Will media law amendments only affect broadcasters or online outlets too? Two opposing views

- ‘All within law’: How president of Azerbaijan destroyed or subjugated media

- Transparency International: Amendments to Georgia’s broadcasting law aim to eliminate critical content

What are the possible consequences for the TV channels?

- Warning

The commission may issue an official warning to the broadcasters—either public or written.

- Demand to correct published content

For example: an obligation to apologise, provide counterbalance, or remove part of the content from a website or social media platform.

- Financial penalty

The fines stipulated by law can be significant. In previous cases, penalties have sometimes been calculated as a percentage of the broadcaster’s budget.

- Temporary regulation or restriction

Before the final investigation is concluded, the commission may impose temporary measures—such as suspending the use of certain expressions.

Expert commentary

Eka Gigauri, Executive Director of Transparency International Georgia:

“It’s clear why Ivanishvili’s Georgian Dream is suing critical TV channels TV Pirveli and Formula.

He doesn’t want the public to know the truth about what’s happening in Georgia. If you analyse exactly which news content the ruling party ‘fears’, in other words, what it believes critical media should not report on, you’ll see the pattern:

1. Investigative reports into corruption within the ruling party

Don’t dare publish a story about opaque assets held by officials, fake tenders, the influence of Cartu Bank (owned by Ivanishvili), or deals with Chinese companies.

The government is terrified of questions like: “Who owns this building?”, “Where was this public money spent?”, “Why did a sanctioned company win the tender?”

2. Critical assessments by independent experts or NGOs

If the broadcast includes views from TI, ISFED, GYLA or any similar organisation—phrases like “democratic backsliding”, “compromised judiciary”, or “election interference”—this will be deemed a “breach of impartiality”.

In effect, words like “authoritarianism”, “elite corruption”, or “state capture” are not to be spoken—even if they come from international sources.

3. Coverage of opposition parties or civil protests where human rights are violated

Don’t you dare show footage of citizens being beaten by police, or opposition leaders speaking about prosecutorial bias—this will be labelled as “campaign coverage”.

Extra caution is needed if protesters mention phrases like “European choice” or “Russian law”.

4. Reporting on election violations or violence

Don’t report on “ballot stuffing”, “biased precinct commissions”, “observer intimidation”, or “officials facing prosecution”—this could trigger a lawsuit over “one-sided election coverage”.

5. Irony, satire, or sarcasm towards the ruling party

If the audience laughs at the government, this can be seen as an “attempt to destabilise”.

For example, if a presenter says: “Bidzina claims Europe is harmful—while his assets are in Europe,” that alone might prompt a complaint to the Communications Commission.

In short, the ruling party has developed a simple manual for ‘safe media’:

- Don’t mention government accountability;

- Don’t portray protests as justified;

- Don’t report on corruption;

- Don’t point to systemic interference in the courts and prosecution;

- Be ‘impartial’, meaning—stay silent.”

On 24 February, during a session of the Bureau of Georgia’s one-party parliament, amendments to the Law on Broadcasting were initiated, introducing restrictions on media activity and effectively imposing censorship. These amendments were soon passed into law.

In particular, under the new rules, broadcasters are prohibited from receiving direct or indirect funding from a foreign state.

Additionally, a clause was added to Article 65 of the Broadcasting Law, banning broadcasters from receiving direct or indirect financial support in exchange for airing social advertisements.