New system of total digital surveillance in Azerbaijan: legal and technological perspectives

New digital surveillance system in Azerbaijan

By decree of President Ilham Aliyev, the State Security Service has established a new system called the “Centralised Information and Digital Analytics System,” abbreviated as MİRAS. The same decree also approved the “Regulations on MİRAS,” which govern the system’s operations.

Although MİRAS is officially presented as a tool to expand the country’s digital capabilities in the security sector, issues related to personal data privacy, legal safeguards, and the risks of potential abuse were not opened for public discussion.

Moreover, the regulations posted on the president’s official website were removed shortly after publication.

This was reported by researcher Javid Aga on his Facebook page.

This article analyses the functions and objectives of the MİRAS system, the scope of data it collects, and the delicate balance between state security and individual privacy. It also compares MİRAS with similar systems in the European Union, examines the risks of abuse under authoritarian governance, and assesses the system’s impact on civil society.

The commentary was prepared by a regional analyst. The terms and place names used, as well as the opinions and ideas expressed, reflect solely the position of the author or the specific community and do not necessarily represent the views of JAMnews or its individual staff members.

Functionality and objectives of the MİRAS system

MİRAS is a centralized information system established within the State Security Service. Its primary purpose is to integrate databases from various government agencies, collect information relevant to national security, enable electronic data exchange, and carry out digital analysis.

According to the regulations, MİRAS is designed to support the State Security Service in exercising its legally mandated powers in intelligence and counterintelligence, operational investigations, counterterrorism, and the protection of state secrets.

Through this system, the State Security Service will be able to rapidly access and analyse data from multiple sources, generate security forecasts, prepare reports, and generally improve the quality of its work in the security sector.

MİRAS will serve as a platform combining traditional operational and investigative methods — such as phone tapping, surveillance, and agent reports — with e-government resources.

The creation of MİRAS also signifies the centralization of information exchange between different government bodies. This involves transferring a significant portion of data to the State Security Service through a single access point.

Scale and scope of data collection

One of the most notable features of the MİRAS system is the scale and breadth of the information it accumulates. The presidential decree provides for the integration of MİRAS with the databases of virtually all key government agencies.

According to the decree, within six months the following ministries and agencies must transfer data to MİRAS through the “e-Government” portal, as listed in Section 3 of the regulations:

- Ministry of Digital Development and Transport – digital government infrastructure and communications data,

- Ministry of Internal Affairs – police data, crime information, and registration records,

- Ministry of Justice – court decisions, penitentiary system data, registration acts, etc.,

- Ministry of Labour and Social Protection – employment, pensions, and social support data,

- Ministry of Economy – registry of commercial legal entities, economic indicators, etc.,

- Ministry of Health – citizens’ medical records, vaccination data, hospital information,

- Ministry of Science and Education – student registry, diplomas, academic information,

- State Committee for Refugees and Internally Displaced Persons – data on individuals with refugee or IDP status,

- State Customs Committee – customs declarations, information on goods and passenger movement,

- State Committee for Work with Religious Organizations – data on religious communities and activities,

- State Migration Service – migration data, border crossings, visas, and permits,

- State Border Service – border crossing and border regime data,

- State Service for Mobilization and Conscription – records of conscripts and military registration data,

- State Tourism Agency – tourist flow statistics and information on tourism sites,

- Agency for Citizen Services and Social Innovations (ASAN xidmət) – data on services received through ASAN, identity documents, registration, etc.,

- Azerbaijan Water Resources Agency – information on water system subscribers and water usage volumes,

- State Examination Center – graduation exam results and certification data,

- OJSC “Azərişıq” – electricity subscriber data,

- Azərigaz – gas subscriber data.

Volume of data collected

The list above shows that MİRAS will effectively gain access to information covering virtually all aspects of citizens’ lives.

From birth to education, from employment to health, from place of residence to religious affiliation, from border crossings to utility usage, a wide range of personal data will be available for analysis by the MİRAS system.

Particular attention is drawn to the inclusion of utility service providers—electricity, gas, and water. This means that, in addition to legal and social information, the system could potentially track everyday behavioural patterns of individuals (for example, residential addresses, utility consumption, signs of presence or absence at home, etc.).

The collection of large volumes of personal data in the name of security is referred to worldwide as “mass surveillance.” Such systems typically contain information on large numbers of people without any specific suspicion of criminal activity. By its scale, MİRAS also appears to function as a mass surveillance tool.

In the European Union, the police agency Europol has collected billions of data points from various countries over the years, effectively creating a “gigantic data repository.” As a result, in 2022, the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) issued a warning to Europol and demanded the deletion of data relating to individuals not connected to any crimes.

The ruling noted that Europol’s database, with a volume exceeding 4 petabytes (equivalent to millions of CDs), contained sensitive data not only on suspects of terrorism and serious crimes but also on asylum seekers and people not involved in any offences. This example shows that even in democratic countries, the collection of such massive datasets is controversial.

Given that MİRAS will receive information from such a large number of sources, its data collection capabilities will be extremely broad. This means that the system’s scope could include not only criminals or potentially threatening individuals but also ordinary citizens.

State security interests versus the right to privacy

Every state is obliged to protect national security. Especially in contexts of terrorism or espionage threats, intelligence agencies in most countries are granted broad powers. However, in democratic societies, these powers must always be balanced against the right to privacy.

Article 32 of the Constitution of the Republic of Azerbaijan prohibits unlawful interference in the personal and family life of citizens.

Additionally, by acceding to the European Convention on Human Rights, Azerbaijan undertook to uphold Article 8 of the Convention, which guarantees everyone the right to respect for their private and family life.

This means that even for security purposes, the state must follow legally prescribed procedures, and any interference must be “necessary and proportionate in a democratic society.”

The MİRAS system sits at the intersection of state security interests and citizens’ right to privacy. On one hand, the State Security Service seeks to implement preventive measures, monitor potential terrorist or criminal networks, and safeguard public safety.

On the other hand, if MİRAS’s powers are excessively expanded, it could create a sense of total surveillance over citizens.

Legal balance requires that intrusion into private life be limited to strictly necessary cases. For example, operational investigative measures such as phone tapping require court approval.

By the same logic, independent oversight mechanisms should exist within MİRAS to control access to personal data. However, it remains unclear how the system’s operations will be supervised.

Risks of abuse in an authoritarian environment

International organisations describe Azerbaijan as a non-free state with elements of authoritarian governance. In recent years, pressure on independent media and civil society has increased, and elections are widely viewed as lacking genuine competition.

In such an environment, the emergence of a high-capacity surveillance tool like MİRAS raises particular concern. With weak mechanisms of democratic oversight, a judiciary dependent on the executive, and limited media freedom, any digital monitoring system can be used for politically motivated purposes.

Existing practice in the country

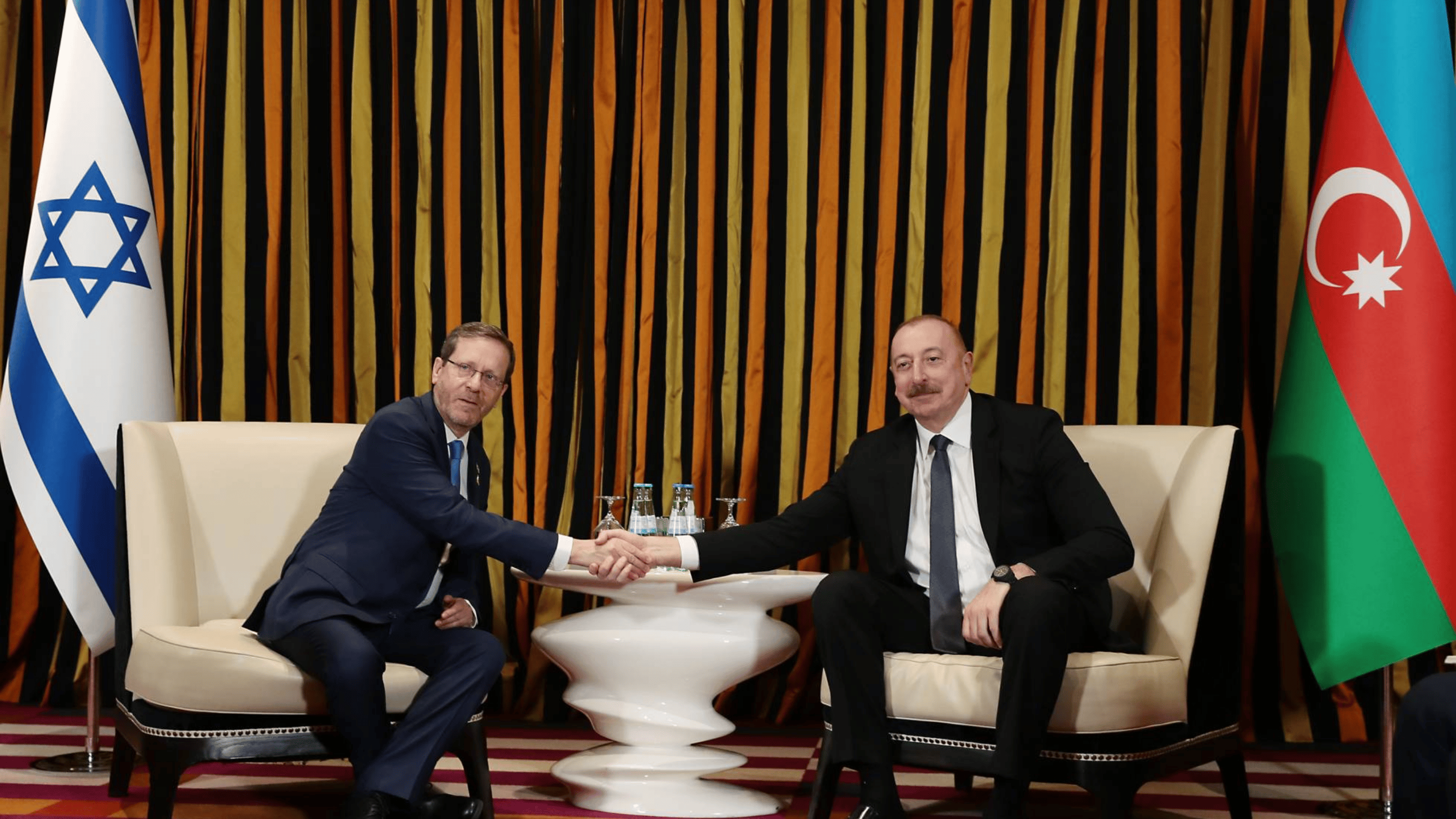

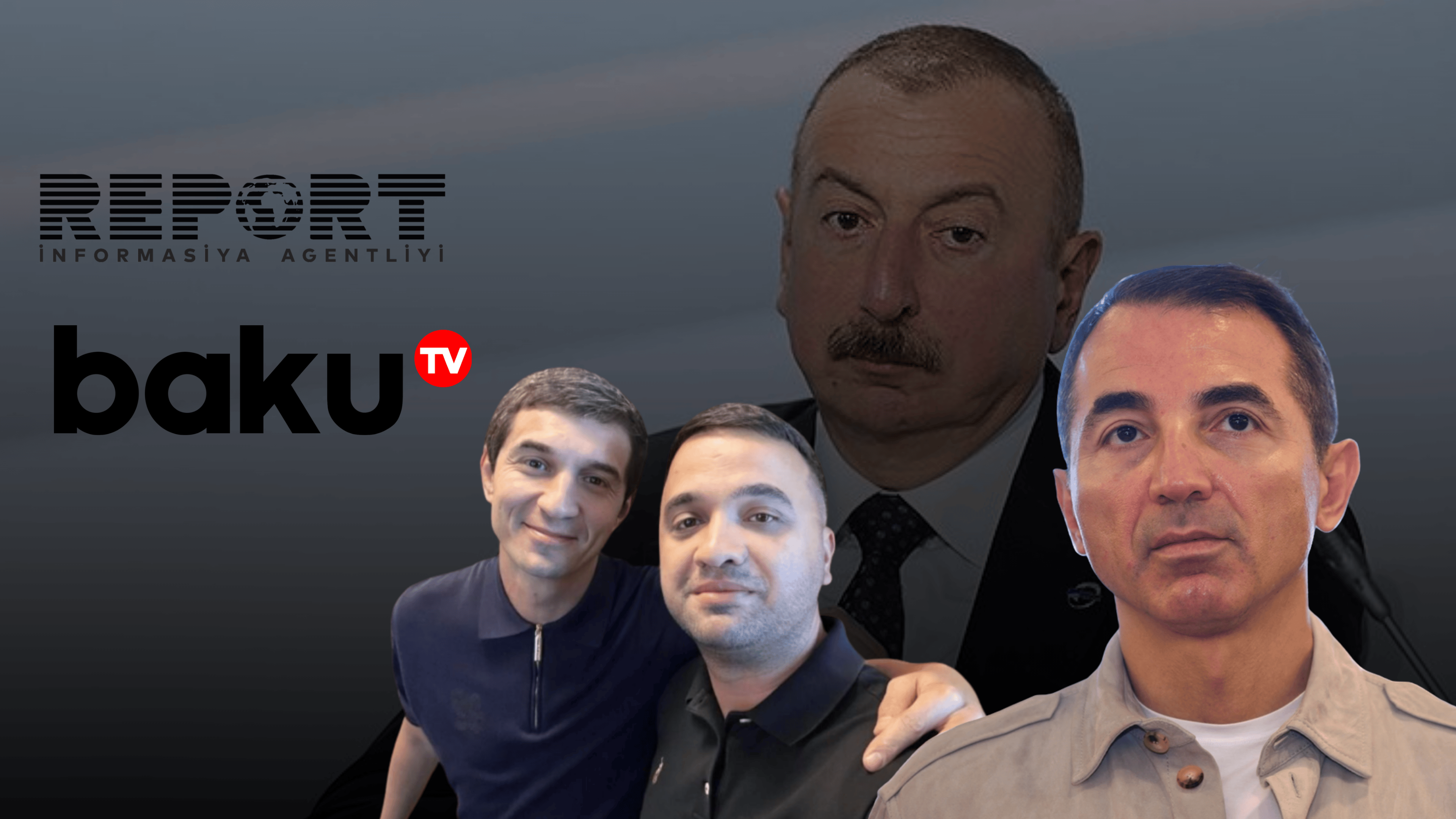

Experience in Azerbaijan shows that technological tools are often used to monitor and pressure dissenting voices. A notable example is the international scandal over the Pegasus spyware in 2021.

It was revealed that the Azerbaijani government had used Pegasus, a powerful surveillance program purchased from the Israeli company NSO Group, to hack the phones of hundreds of people, including journalists, human rights defenders and opposition politicians. The software allows covert interception of calls, messages and photos, as well as access to a phone’s microphone and camera.

Investigations by OCCRP and Amnesty International found that the leaked data included the numbers of 245 people linked to Azerbaijan, most of them journalists, activists or opposition figures. In other words, the authorities used this software to monitor them.

Despite official denials, independent experts provided compelling evidence that “advanced surveillance tools were acquired to monitor government critics.”

This case illustrates that in Azerbaijan, digital surveillance tools are deployed more often against domestic critics than against terrorists or external threats.

Potential abuse scenarios

It is not hard to imagine the potential consequences of introducing the MİRAS system. For example:

- Surveillance of political opponents: Movements of opposition figures within the country, their social networks, financial situation and public activities could be easily tracked through MİRAS. Such data makes it simpler to fabricate criminal cases.

- Targeting journalists and activists: Authorities could monitor travel of critical journalists, their meetings abroad, domestic contacts, and, if telecommunications data is integrated, even their text messages. This gives the government the ability to identify information sources or exert preventive pressure.

- Blackmail and threats: There have been past instances where compromising personal information, including secretly recorded intimate videos, was used against government critics. As MİRAS accumulates massive amounts of personal data, the risk of unauthorized access and dissemination grows. If the database is misused by unscrupulous employees or hacked, private information could end up on the “black market.”

The Azerbaijan Internet Watch project notes that law enforcement agencies already have near-unlimited access to personal data, and effective safeguards do not exist. This means that information collected by MİRAS could at any time be used “by order from above” for any purpose, with no apparent institutional barriers.

Issue of legality

The main factor increasing the risk of abuse is the absence of independent judicial oversight and genuine accountability under the law in Azerbaijan. While the Constitution prohibits surveillance without a court order, in practice courts often play a formal role, approving law enforcement requests without scrutiny.

In other words, the State Security Service (SSS) can obtain judicial authorization for monitoring or wiretapping, but no one verifies the legality of these decisions. Members of parliament do not raise these issues, and the ombudsman’s office remains largely inactive.

As a result, oversight of potential violations within the MİRAS system effectively comes down to “self-monitoring,” which cannot be considered an effective safeguard.

Need for public and parliamentary debate

In democratic processes, it is crucial that decisions affecting society are subject to broad discussion, take into account different viewpoints, and are made transparently.

However, the MİRAS system was neither publicly debated nor discussed in parliament. It was established by a direct presidential decree and announced to the public only through a brief note in the official media.

At the same time, the centralization of personal data on such a scale affects every citizen and should, in principle, have been considered in the Milli Majlis through a dedicated law. Given the lack of transparency in Azerbaijan’s parliamentary elections, such discussions would likely have been formal at best.

If the government truly has nothing to hide and its sole purpose is national security, why was the process conducted in secret?

Open discussion, on the contrary, would have allowed public concerns to surface and provided an opportunity to make adjustments that could address them.

Новая система цифрового контроля в Азербайджане