Epidemic prevention a century ago in the Caucasus: wash your mouth with soap and don't kiss your mother

Exactly one century ago in the Caucasus, in the spring of 1920, like all over the world, locals were struggling through the terrible Spanish Flu pandemic. What did doctors recommend at the time and how did newspapers cover this topic?

This overview is based on the coverage of the Spanish Influenza in Georgia and various simultaneous epidemic illnesses in Dagestan, found in Sasoplo Gazeti (“Village Newspaper”) and Volny Gorets (“Free Mountaineer”), respectively.

- How the elderly are coping with isolation-Video

- Georgia: strict new coronavirus restrictions until end of January 2021

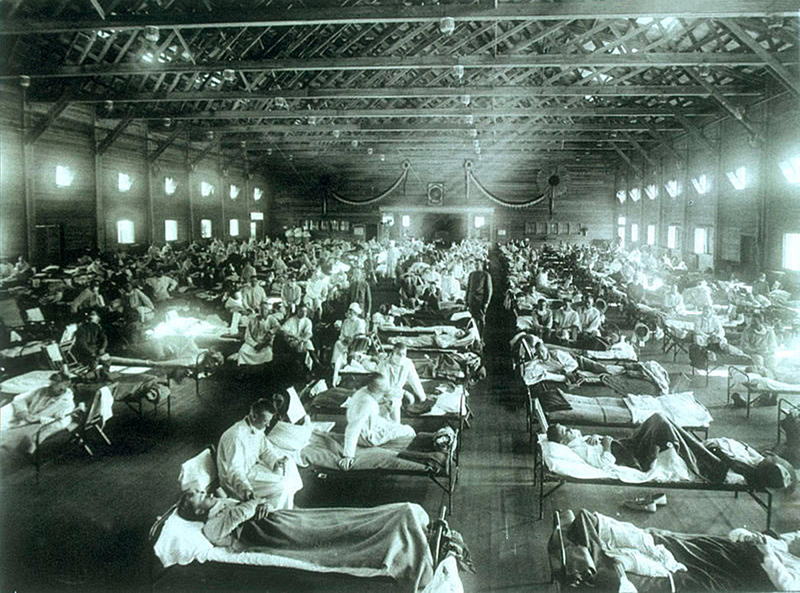

The Spanish Influenza pandemic of 1918-1920 caused the most massive loss of human life in the history of mankind. According to the modern estimates, approximately 500 million people contracted the Spanish Flu – about one-third of the world’s population – and between 50 and 100 million passed away as a result of the illness.

The number of victims of the Spanish Flu pandemic is comparable to the losses of both World Wars: the first claimed between16 and 22 million lives; the second, 60-80 million.

In addition to the Spanish Flu, local populations simultaneously endured outbreaks of Typhus, Avian Influenza, and insect-borne Relapsing fever.

This occurred against the backdrop of World War I, the Russian Civil War, and Turkish offensives into the Caucasus region, all of which damaged public health infrastructure and made addressing these epidemic illnesses extremely difficult.

Disease prevention: keep your nose clean

The Georgian-language newspaper Sasoplo Gazeti featured a regular column in which a doctor, known only as ღ. (“gh”), offered medical advice to readers. He emphasized that they should take preventative measures to avoid illness and explained complex topics, such as the transmission of infectious disease, in simple terms.

In an April 18th, 1920 column about influenza, Dr. Gh explains: “because the influenza contagion enters the body through the nose and throat, it is necessary to keep these areas healthy and proper”.

He also underscores the importance of disinfecting all utensils and linens used by patients in boiling water.

The disease, he notes, is often spread within families. Therefore, he stresses the need to maintain physical distance from anyone who is sick: “It is also harmful when a mother who is ill puts her baby to bed. This is tantamount to passing it on. Kisses also help to spread the illness. It is better for a mother to stay away for a few days, in this case, than to make her child sick by exposing him to this dangerous love”

Finally, he cautions that “drinking wine, carousing, staying up late, tiredness, and physical exhaustion all greatly contribute to the spread of disease”

Medicines: sniffing camphor and gargling disinfectants

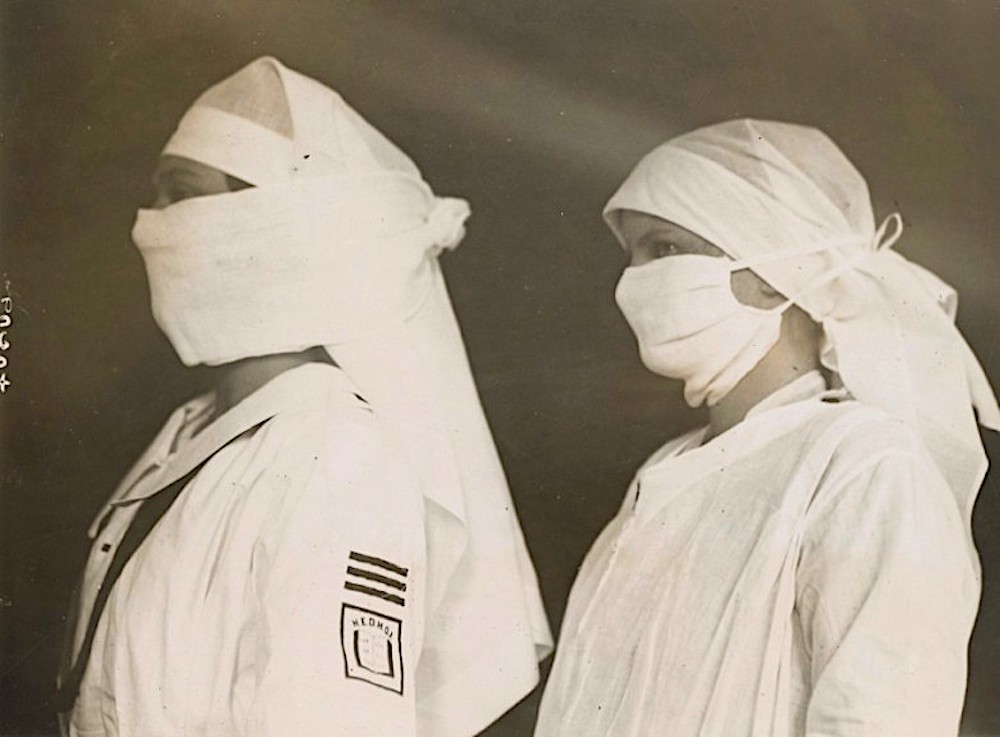

Both the medical adviser for Sasoplo Gazeti and Dr. Orlov of the Red Crescent Society, who was interviewed in the newspaper Volny Gorets, recommended the oral inhalation of camphor and alcohol solutions for those coming into contact with the ill.

Cleaning the throat and nasal cavities with a solution of “Berthollet Salt” was also recommended. Once the patient felt a “burning sensation” in the back of their throat, they were to remove the medicine immediately. Better known as Potassium Chlorate, this highly flammable substance is still used in industrial contexts for its disinfectant properties. Potassium Chlorate was discovered to be toxic for human consumption in the early 20th century but was, nonetheless, still sold in pharmacies.

Government responses and international medical assistance

In the complex geopolitical environment of the early 1920s, coordinating medical assistance could be extremely difficult. Due to frequent shifts in borders, sending medical missions outside of major cities could be both costly and dangerous.

After diplomatic requests for assistance, the Dagestani Red Crescent (the national affiliate of the International Committee of the Red Cross) spearheaded efforts to manage the typhus and Spanish flu outbreaks in the region.

Although the spread of the Spanish Influenza was stymied rather quickly, Dr. Orlov noted that it was highly lethal, with a 90% fatality rate after symptoms appeared.

The author would like to thank the Ilia Chavchavadze National Parliamentary Library of Georgia for their permission to republish parts of articles from their Iverieli Digital Collections.