Why Azerbaijan is seen as threat to Iran amid ongoing protests

Azerbaijan’s stance amid protests in Iran

Amid a surge in mass protests in Iran, the issue of “South Azerbaijan” has once again moved to the forefront of the regional agenda. In this context, the Azerbaijan has become one of the key actors watched particularly closely by Tehran, both because of the presence of ethnic kin across the border and Baku’s close ties with the United States and Israel.

Since the final days of last year, mass protests have swept major Iranian cities amid a sharp depreciation of the national currency and rising prices. The demonstrations, which began on 28 December in the Grand Bazaar area of Tehran, quickly spread to cities including Mashhad and Isfahan.

Against the backdrop of severe inflation (officially reported at more than 50% year on year), people have taken to the streets in protest against impoverishment, shortages of food and medicines, and unemployment. Demonstrations that initially focused on social demands soon took on a political character.

State authorities first attempted to contain the protests, but the situation quickly spiralled out of control. Clashes have now continued for more than two weeks, with protesters being killed as a result of state actions. Independent human rights groups report that on 8–9 January, hundreds — and possibly thousands — of people were killed in several cities after security forces used live ammunition against peaceful demonstrators.

Footage circulating on social media shows hundreds of bodies laid side by side in body bags at the Kahrizak morgue in Tehran. The Iranian government has not released full information on casualties, but has acknowledged that at least 109 police officers and security personnel were killed during the unrest.

According to experts, the protests do not yet have the capacity to bring about the immediate overthrow of the regime: the security apparatus remains cohesive, and a full collapse of the system in the next one to two months is considered unlikely. An assessment by Janes suggests that in the short term the government may attempt to quell the protests by offering limited socio-economic concessions.

This commentary was prepared by a regional analyst. The terms, toponyms, views and assessments used reflect solely the position of the author or a specific community and do not necessarily represent the views of JAMnews or its staff.

US, Israel and Azerbaijan: how alliance is closing in on Tehran

The Iranian regime views the current crisis not only as the result of domestic problems, but also as a consequence of geopolitical shifts in the region. In particular, developments in recent years in the Middle East and the South Caucasus have narrowed Iran’s traditional sphere of influence.

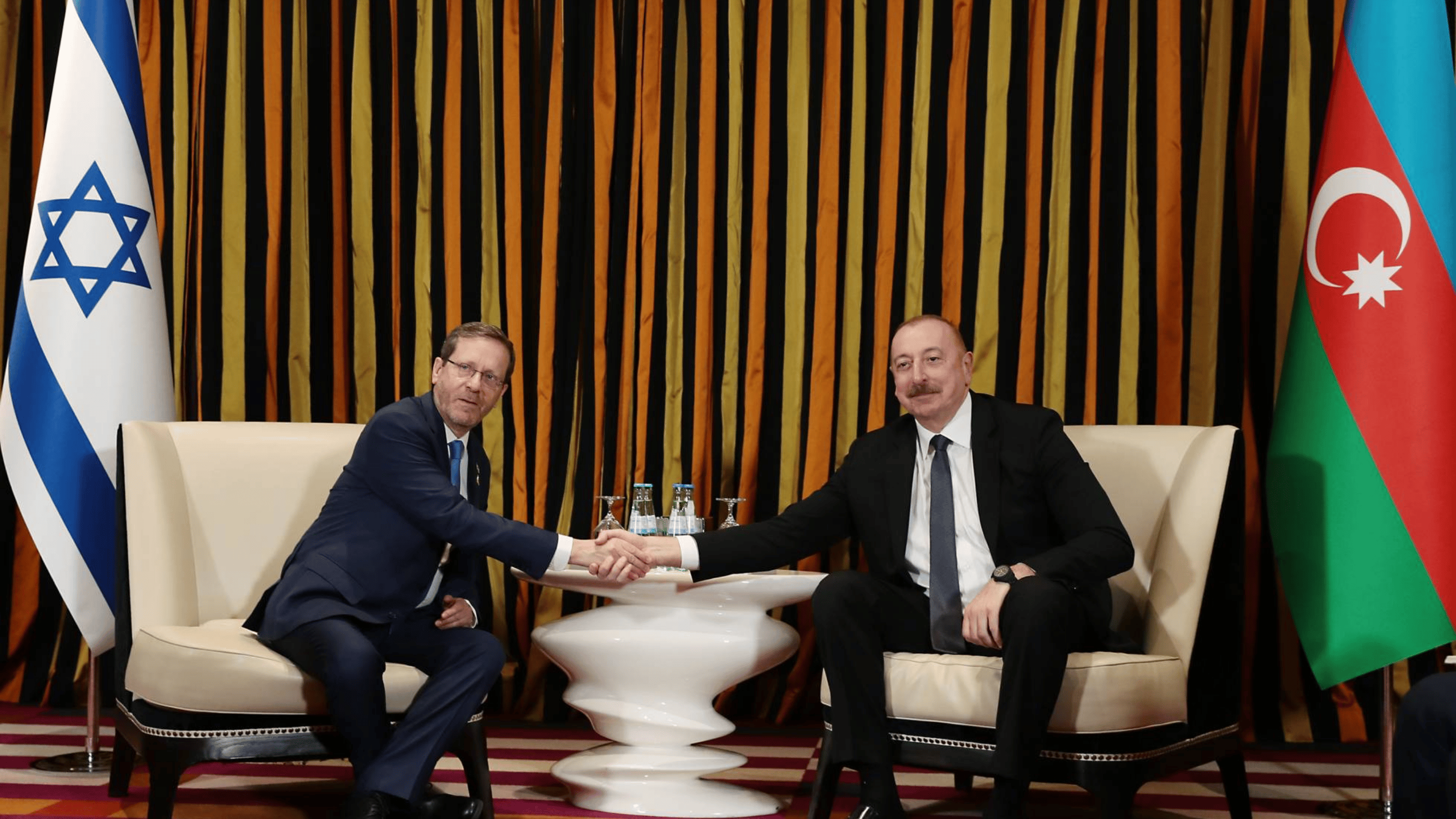

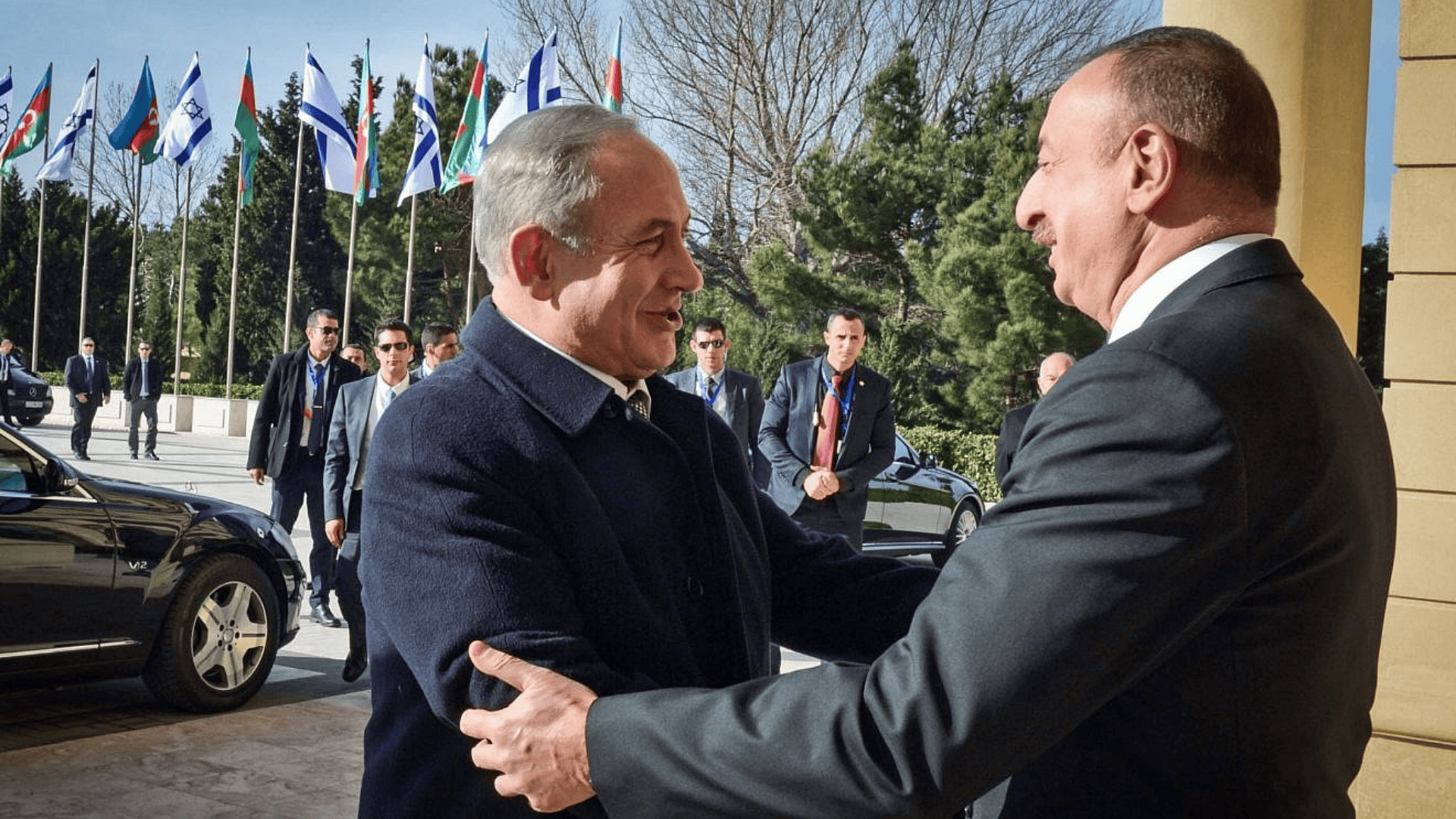

In this context, the role of the Republic of Azerbaijan merits particular attention. Over the past three years, Azerbaijan’s strategic partnership with Israel and its military-political alliance with Turkey have significantly altered the balance of power in the South Caucasus, to Tehran’s disadvantage.

During the Second Nagorno-Karabakh war in 2020, modern weapons supplied by Israel to Azerbaijan — including drones and precision-guided missiles — not only contributed to Baku’s victory, but also provided Israel with a strategic ally on Iran’s borders.

As noted by the Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, Azerbaijan serves as an accessible platform for Israel “at Iran’s back door”. This cooperation enables Tel Aviv to obtain intelligence on Tehran and, if necessary, to acquire operational capabilities in close proximity to Iran.

One of the more alarming signals for Tehran came in September 2023. While Russia was focused on its war against Ukraine, the Azerbaijani army took control of previously occupied territory in Karabakh, dismantled the structures operating there, and saw Russian peacekeepers withdraw from the region.

As a result, the decades-old “frozen conflict” order in the South Caucasus was disrupted. A new phase began along Iran’s northern borders, in which Russia lost its decisive influence, while the role of Turkey and the West — including Israel — increased significantly. Baku emerged as a “middle power” in the region and began pursuing a more confident and independent policy.

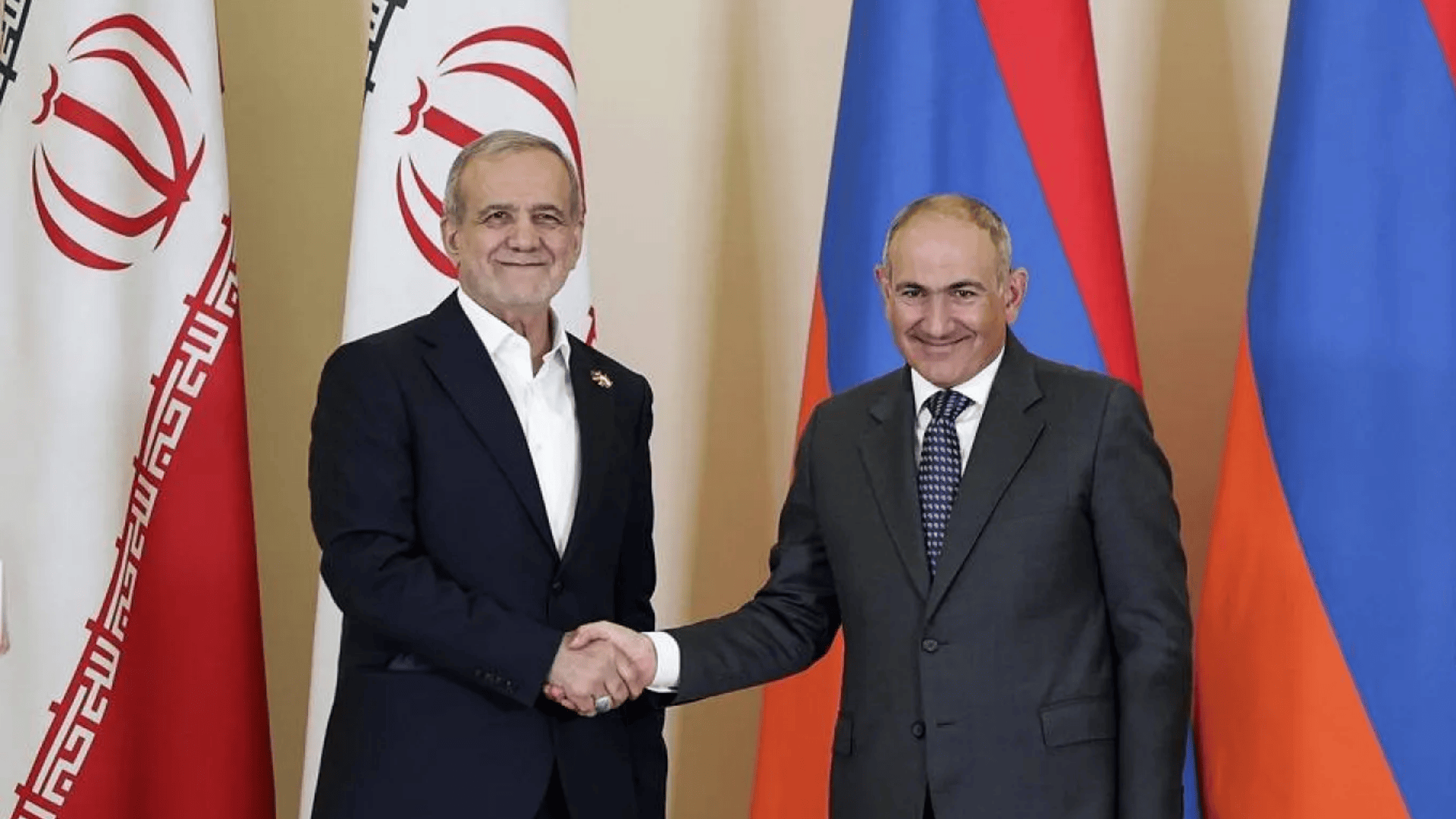

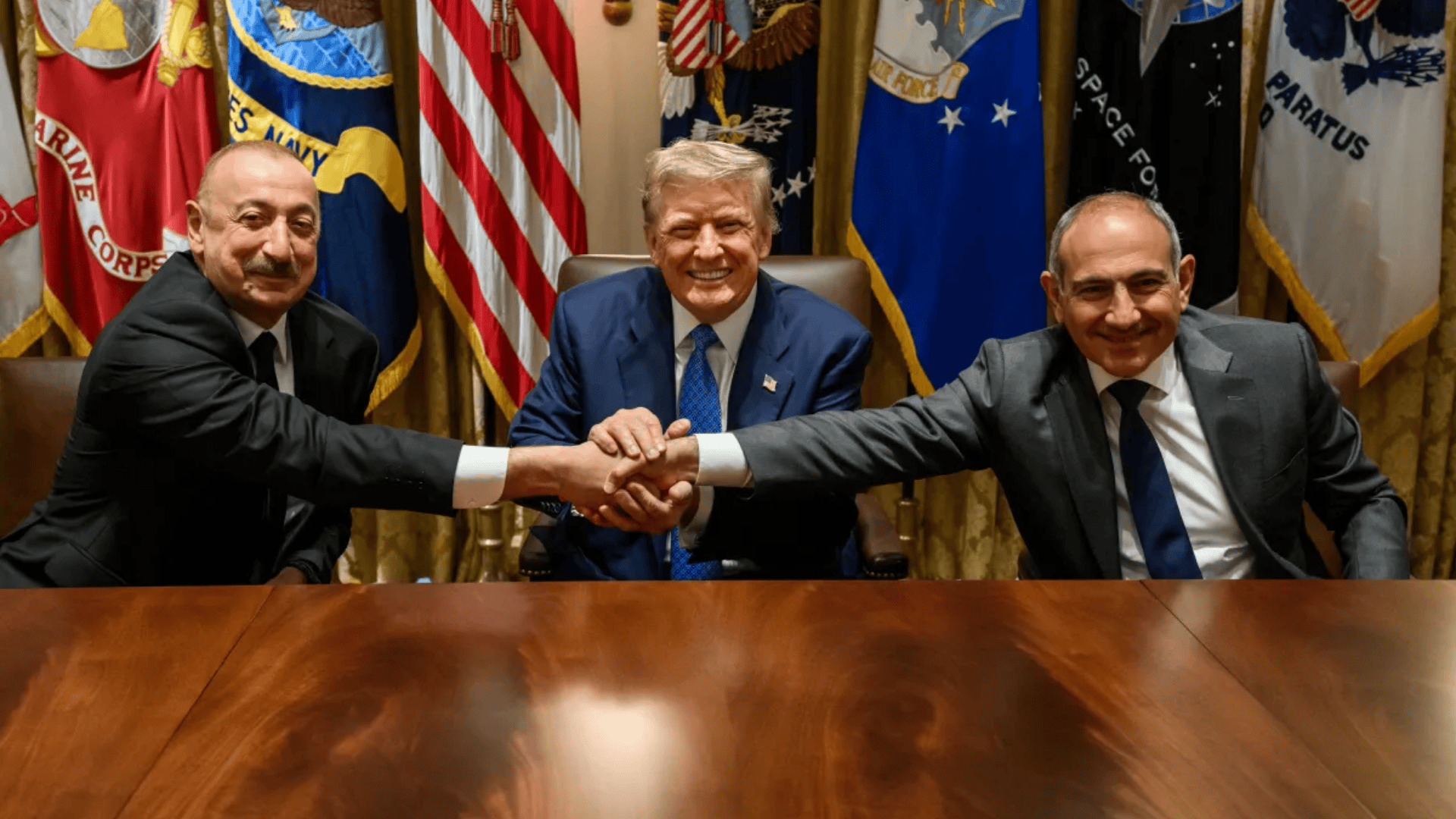

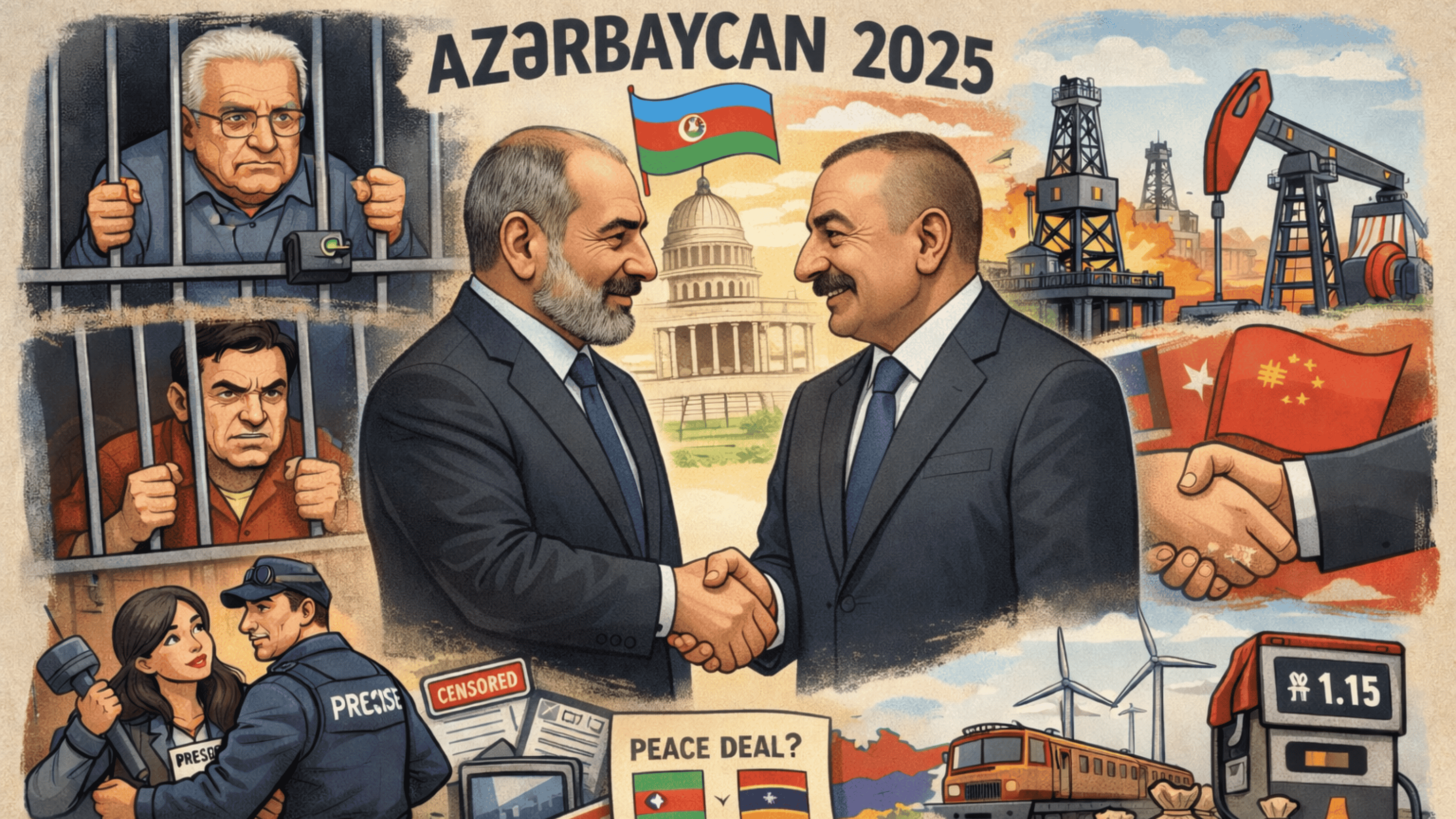

This rise of Azerbaijan has caused concern in Tehran. For a long time, Iran had supported Armenia, thereby maintaining its positions in the South Caucasus. However, Armenia is now also signalling a course towards closer ties with the West. In August last year, with the mediation of US President Donald Trump, Yerevan and Baku reached important agreements on a peace settlement.

Under these agreements, a plan was announced to open a 42-kilometre route intended to link Azerbaijan with Nakhchivanvia a territory referred to by Baku as Zangezur. The route was even given the name Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity (TRIPP). Even if largely symbolic, this was presented as a diplomatic success for Washington in the region.

Tehran, for its part, openly voiced strong objections, fearing that the corridor could allow the US and Israel to move closer to its borders. The Iranian leadership now views both a potential US military-logistical presence from the west, via Armenia, and the activity of Israeli intelligence and sabotage structures from the north, via Azerbaijan, as a direct threat to national security.

Thus, Iran finds itself facing a trilateral alignment involving cooperation between the United States, Israel and Azerbaijan.

Although this cooperation is not openly declared, it is perceived by Tehran as a tangible reality. Iranian media periodically claim that Azerbaijan assists Israel in establishing an intelligence network on its territory, allows the use of its airfields by Israeli drones, and provides other forms of support.

In 2024, Iranian intelligence circulated video materials alleging the existence of a network operated by Israel’s intelligence service, the Mossad, in Azerbaijan. While Baku has officially rejected these accusations, the scale of Israeli-Azerbaijani military cooperation is no longer a secret.

According to the Stockholm International Peace Research Institute (SIPRI), Azerbaijan has sourced a significant share of its arms imports from Israel over the past decade. In return, Israel gains access to Azerbaijani oil resources and secures a reliable partner along Iran’s borders.

The US has also been developing strategic ties with Azerbaijan. The rapprochement between Washington and Baku became particularly visible during the administration of US President Donald Trump. Trump was reportedly so pleased with a meeting in Washington that he presented Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev with a signed photograph bearing the inscription: “Ilham, you are magnificent, you are a great leader.”

Aliyev, for his part, praised Trump’s efforts to resolve the Karabakh conflict and establish peace in the region, expressing his deep gratitude. Moreover, the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia jointly announced their intention to nominate Donald Trump for the Nobel Peace Prize.

All this points to the highly positive nature of the Baku–Trump line, something that cannot but alarm Iran. Washington gains leverage both in the South Caucasus and indirectly over Iran, using Baku as a channel of influence.

Trump has also openly voiced support for Iranian protesters. On 9 January, he shared on his Truth Social account an English-language report by Azerbaijani online broadcaster Channel 13, run by independent blogger Aziz Orujov, who was recently released from detention.

In the post, Trump wrote: “More than one million people have taken to the streets: Iran’s second-largest city, Mashhad, has fallen under the control of protesters, and regime forces have left the city,” welcoming what he described as the rise of the Iranian people.

This episode, however symbolic, suggests that the White House is willing to use even Azerbaijani media content as a tool to influence public opinion in Iran. Tehran, there is little doubt, views such steps as part of an information war directed against it.

The Iranian side is not without support either. Official Iran is counting on assistance from Russia and China. Moscow openly states that it opposes external interference in Iran’s internal affairs and, at the diplomatic level, aligns itself with Tehran.

Kremlin representatives urge the West not to pursue a “colour revolution” scenario in Iran and say Russia is ready, if necessary, to help meet Iran’s economic needs — for example, by arranging emergency supplies in the event of shortages of petrol or flour.

At the same time, Russian experts, including Sergey Markov, acknowledge that “there is no formal military alliance between Russia and Iran, and Moscow will not enter a direct war for Iran.” In other words, the Kremlin limits its backing to the diplomatic and political sphere, while acting cautiously on the military front.

China is demonstrating a similar approach. Beijing does not offer Iran open political support, but continues to cooperate with Tehran in the energy and trade sectors despite Western pressure.

Both China and Russia are adopting a wait-and-see posture towards the Iranian crisis. One reason is their concern about unpredictable moves by the Trump administration, including episodes such as the detention of Venezuelan President Nicolás Maduro.

Overall, global players are divided over the Iranian crisis. The European Union fears destabilisation, new refugee flows and an energy crisis in the event of war. The United States, by contrast, is pursuing a strategy aimed at maximising pressure on Tehran. These differences are causing friction even within NATO, where some European allies do not support Trump’s hard line.

Within this complex international configuration, the position of Azerbaijan takes on particular significance. Tehran openly claims that it was Azerbaijan that brought the Israeli factor into the South Caucasus. Iranian generals have repeatedly accused Baku of having “thrown open its arms to the Zionists”, and in 2021 the Iranian army conducted large-scale exercises along the Azerbaijani border, sending what it described as a warning signal to “foreign — that is, Israeli — forces”.

Baku, responding to these accusations, stresses its sovereign right to cooperate with any states of its choosing. In practice, however, Azerbaijan is forced to strike a delicate balance. On the one hand, open confrontation with Tehran carries risks, including military tension along the border, the influence of the Shia religious factor domestically, and trade and economic ties. On the other, support from strategic partners such as Israel and the United States strengthens Azerbaijan’s regional position.

‘South Azerbaijan’ scenarios in pro-government media

Official Baku has so far refrained from making high-profile statements at senior level about developments in Iran. However, Azerbaijani pro-government media and commentators have been relatively outspoken. In their interpretation, the Iranian regime is facing collapse, and the current situation could open up what they describe as historic opportunities for Azerbaijan.

Analytical pieces published by Modern.az, a website widely regarded as close to the Azerbaijani authorities, argue that the protests in Iran reflect a “crisis of internal legitimacy”. These articles claim that the Iranian regime, having for many years deprived its own population of social welfare while diverting resources to support terrorist groups, effectively engineered the economic crisis and is now confronting its severe consequences.

Russian political analyst Sergey Markov, whose interview was also published by Modern.az, focused in particular on the situation of “South Azerbaijan” — a term used to describe ethnic Azerbaijanis living in Iran’s north-western provinces — and offered a series of high-profile assessments.

According to Markov, if Iran were to embark on a scenario of potential fragmentation along ethnic lines,

“Azerbaijanis in South Azerbaijan would face an extremely difficult choice: to remain within Iran, to create an independent state, to unite with Northern Azerbaijan [the Republic of Azerbaijan], or to form a temporary political union with Baku.”

He argues that if events were to accelerate, the Azerbaijani state could be compelled to take a more active stance to protect its ethnic kin in “South Azerbaijan”. The very fact that such statements are being amplified by pro-government media, he suggests, indicates that Baku is indeed considering this scenario.

In another analytical article on Modern.az, author Elnur Amirov, assessing the geopolitical consequences of the Iranian crisis, writes:

“The Baku–Tabriz line could play an important role in the new world order. The road from Baku to Tabriz is no longer merely aspirational and is becoming part of a new geopolitical reality.”

Implicitly, this suggests that a direct link between Azerbaijan and Iranian Azerbaijan — potentially even in the form of political integration — is being discussed as a realistic prospect. The fact that pro-government analysts are advancing such explicit arguments highlights the prominence of the “South Azerbaijan card” in the thinking of Azerbaijan’s political elite.

In Azerbaijani society, the issue of Iran’s north-western regions — historically referred to as South Azerbaijan — is a sensitive and emotionally charged topic. Since Azerbaijan gained independence in 1918, many political figures have kept the fate of ethnic Azerbaijanis in Iran within their field of attention.

Although official Azerbaijan long demonstrated caution, stressing respect for the territorial integrity of Iran, nationalist rhetoric has become noticeably more pronounced in the state media sphere in recent years.

In October 2024, for example, a presenter on Azerbaijan’s state television channel AzTV stated live on air that “southern Azerbaijanis are subjected to countless forms of oppression, send dozens of messages every day, and all want to unite with us”.

Commenting on the statement, Iran’s influential website Tabnak observed:

“It is unlikely that such claims are made without coordination with the Azerbaijani authorities.”

The article highlighted the provocative nature of such signals coming from Baku. The Iranian side believes that the Azerbaijani authorities are deliberately using state television to stoke sentiment among Iran’s Turkic population and sow the seeds of separatism.

While official Azerbaijani representatives reject these accusations, pro-government political commentators tend to emphasise the South Azerbaijan factor in discussions about Iran’s future. Some pro-government experts go further, openly arguing that “Baku should already be preparing for a scenario involving Iran’s disintegration and developing a plan of political and diplomatic manoeuvring”.

Such arguments regularly appear on platforms including Modern.az and Caliber.az. One analytical piece on Modern.az, published around the time of an interview with Russian analyst Sergey Markov, claimed that “Tehran is shaking, street uprisings are beginning across Iran, Ukraine has already been forgotten”, adding that “Ankara and Baku must be ready for what is unfolding in the region”.

Such headlines send a clear signal to Azerbaijani audiences: that the weakening of the Iranian regime could be transformed into a strategic advantage for Azerbaijan.

At the same time, Azerbaijani media are also debating the role of the Turkic population of “South Azerbaijan” in the Iranian protests. Some pro-government commentators, with a note of regret, observe that for now southern Azerbaijanis are not at the forefront of the protest movement.

They attribute this to the fact that Iranian Azerbaijanis have historically played a leading role in every revolution, only to become targets of repression each time. On this occasion, the authors argue, they have adopted a wait-and-see approach in order to avoid yet another futile and risky venture.

“South Azerbaijan” organisations, including the Coordination Council of South Azerbaijan Organisations, have issued a statement on the latest protests, stressing that peaceful demonstrations are also their legitimate right, and announcing plans to hold a solidarity march in Tabriz on 10 January.

They emphasise that market traders and the Azerbaijani community in the south more broadly are among the first victims of the current economic crisis and intend to pursue a peaceful struggle for democratic rights. In other words, political forces in South Azerbaijan are, at this stage, advocating reforms and the protection of rights within the territorial integrity of Iran.

Taking this into account, some political analysts warn that it would be a mistake to view all Iranian Azerbaijanis as separatists. A significant proportion see the realisation of their rights precisely within a federal or democratic Iran. Accordingly, even if the regime weakens, the question of how the future of South Azerbaijan would be resolved — whether through independence, unification, or autonomy — remains extremely complex and sensitive.

Possible steps and Azerbaijan’s position

According to forecasts, if the regime in Iran weakens and embarks on a path of reform, Azerbaijan would welcome such changes while maintaining a cautious approach. In the event of a complete change of power in Iran — for example, the emergence of a secular interim government — Baku would seek to establish contacts with the new leadership as quickly as possible.

Azerbaijan already has certain links with segments of the Iranian opposition. This is evidenced by the participation of Azerbaijani diplomats in international conferences dedicated to opposition to the Tehran regime. If, in possible post-regime scenarios, the question arises of granting South Azerbaijan autonomy or expanded rights, Baku could offer indirect support for such arrangements.

The most complex scenario would be an ethnically driven disintegration of Iran. In that case, Azerbaijan could face a historic choice:

Whether to recognise the proclamation of an independent Republic of South Azerbaijan, attempt to incorporate it, or remain on the sidelines of unfolding events.

Commentators such as Sergey Markov advise Baku to prepare in advance for all these possibilities. Naturally, the implementation of such a dramatic scenario would draw in other actors, including Russia and Turkey.

Russia has already stated that it would oppose any violation of Iran’s territorial integrity and would seek to prevent its collapse. Turkey, by contrast, could adopt a more sympathetic stance ideologically on the issue of safeguarding the rights of Turkic communities in South Azerbaijan.

Within such a geopolitical configuration, Azerbaijan’s role would become critically important. It is highly likely that Baku would preserve ambiguity in its public position for as long as possible, first seeking to understand which scenario key international players — such as the United States, Russia, Turkey and the European Union — favour.

Previously, amid rising tensions between Tehran and Baku, many analysts noted that Azerbaijan, by promoting a secular and ethnically close model of development, could act as a kind of “velvet centre of attraction” as an alternative to Iran’s theocratic regime.

Today, this forecast appears to be partially materialising: some Iranian Azerbaijanis view the economic prosperity and secular lifestyle of the Azerbaijani Republic to the north as a model to emulate.

At one time, former US diplomat Brenda Shaffer wrote that “Azerbaijan’s secular government and liberal society offer an alternative model to Iran’s theocracy”, one that could be particularly appealing to Azerbaijani Turks in Iran. Today, thousands of young people chanting “Freedom!” on Iran’s streets may well be turning their gaze towards Baku — towards the image of a “free and prosperous Azerbaijan in the north”.