The Georgian funerals of yesterday and today

Funeral rituals and mourning traditions in Georgia

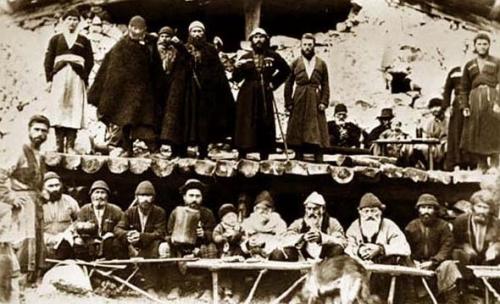

In the 17th Century, the famous Italian missionary Arcangelo Lamberti described the Georgian (more precisely Megrelian) funeral table as follows:

“After the funeral, everyone returned to the house of the deceased, where dinner was waiting. The most honorable place at the table was given to the priest who read prayers for the deceased. Food was served in abundant quantities, but largely with modest dishes – some of the food was brought by the guests themselves.

“There was a lot of wine, but no one touched the wine until the priest present at the dinner took a bowl of wine in his hands, read the memorial prayer for the deceased in a low voice, and poured some wine from the bowl to the ground.

“This was repeated five or six times at dinner, and the deceased was no longer remembered. The participants of the feast then spent the time quite joyfully. The end of the dinner meant the end of the funerary ritual.”

Most remains unchanged today, but there are rituals that have not survived.

JAMnews author Levan Sebiskveradze looked into different mourning traditions in Georgia.

Professional mourners and the tavi katsi

Approximately 20 years ago in Western Georgia, mainly in the Samegrelo region, there was a custom of hiring mourners. These were usually middle-aged women and older who could skillfully depict deep sorrow. Legends about them are still around today.

The most “popular” among them grew their nails and scratched their faces bloody as a sign of grief, alternating it with uncontrolled endless sobs. The services of such mourners were quite expensive.

• Dying in Azerbaijan: prices, rules and rites

• Eat, pray, drink – Easter traditions in Georgia

• Op-ed: When and why did bottled wine culture disappear in Georgia?

Unlike the mourners, the informal position of a tavi katsi survived: a sort of manager responsible for organising a memorial service, the funeral and wake. This responsibility was generally taken up by a relative or neighbour who was able to deal with technical and organisational issues.

Traditionally, wakes were held either in the house of the deceased, or in the central places of villages or small towns. In recent decades, memorial tables have been laid out in ritual or ceremonial halls.

But the role and functions of a tavi katsi have not disappeared.

Today, it is this person (sometimes even without coordination with the family of the deceased) who decides where the grave should be, which coffin should be ordered, who should raise funds to help the family bereaved by grief, where to set up the funeral table etc.

In Georgia, the immediate relatives remain in mourning for one year. There are a series of other dates such as “the forties”. Forty days after the funeral, the family arranges another memorial feast, more modest than that of the funeral, and the same tavi katsi regulates all these issues.

The bitter taste of Georgian mourning wine

Although Georgians are proud of the antiquity of winemaking and the culture of wine consumption, there are many low-quality wines made without the use of local technology, such as using sugar water to produce larger quantities. This appeared in the “planned management” of Soviet times.

This bad and harmful “tradition” is used at wedding or memorial feasts when there are a lot of guests. Such wine has even acquired its own name – memorial wine.

The organisers of a crowded feast often decided to save a bit of money when it comes to wine, and as a result, the entire feast loses its meaning. For people versed in wine, such a feast becomes a heavy burden, given that it is one’s task to intoxicate large crowds.

A toastmaster of a memorial feast usually follows the rules of wine consumption adopted in Georgia and delivers a limited amount of toasts. Previously, the number of toasts was supposed to be odd – three (rarely seven). Usually, toasts were dedicated to memories such as those of the departed, and at the same time meant to have a symbolic connection with the continuation of life.

Georgian commemoration – theatrics and competition

Georgian mourning rituals are almost always dramatised. Daughters compete with each other over who can mourn their deceased mother-in-law more loudly and artistically (even when they didn’t love her in life). Wealthy relatives emphasize their closeness to the grieving family by the amount of money they donate.

Anyone who has anything to do with the grieving family, even if they did not know the deceased personally, tries to express their condolences.

In previous times, when horses were the main means of transportation, it was difficult to get to some highland villages in time, or to go from one region to another, and even the connection between neighboring villages was often poor for various reasons.

Because of this, mourning events in the mountains (for example, in the Svaneti region) continued for several days so that relatives could have time for funerals. Unfortunately, even today, it is difficult to get to some places on time.

That is why in some parts of Georgia there is a tradition to receive guests who have arrived from afar – they are taken to tables specially laid for them, and specially designated by the tavi katsi.

Naturally, according to Georgian traditions, such guests were not only fed, but treated with wine, and the hosts themselves had meals according to the laws of hospitality with guests arriving from distant regions. As a result, there are often no sober individuals in attendance at funerals in Imereti, Samegrelo, Adjara and Guria regions by the time the burial takes place.

Other such complications arise in high-altitude villages: drunken mourners get lost, fall off the road, or coffins slip into ravines, from where it is difficult to pull out even a living person, nevermind a coffin with a corpse.

Today, funeral traditions in Georgia seem to be “standardized” and arranged as is customary in the regions of Kartli and Kakheti: memorial tables are laid only after the deceased is buried and all participants in the funeral ceremony leave the cemetery. Only the gravediggers remain and are then treated to food and wine by the relatives of the deceased afterwards.

Each gravedigger, especially in large cities, has to bury more than one deceased per week, and, accordingly, dines many times. Therefore, it is almost impossible to meet a gravedigger in Georgia who leads a sober lifestyle.