The end of Putin’s pipelines: how Europe cut its reliance on Russian gas

Europe is breaking free from Russian gas

Russian gas no longer dominates Eastern Europe or dictates geopolitics through pipelines. Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, the end of gas transit through Ukraine and soaring prices forced countries in the region to diversify supplies, turning to Turkey and Azerbaijan.

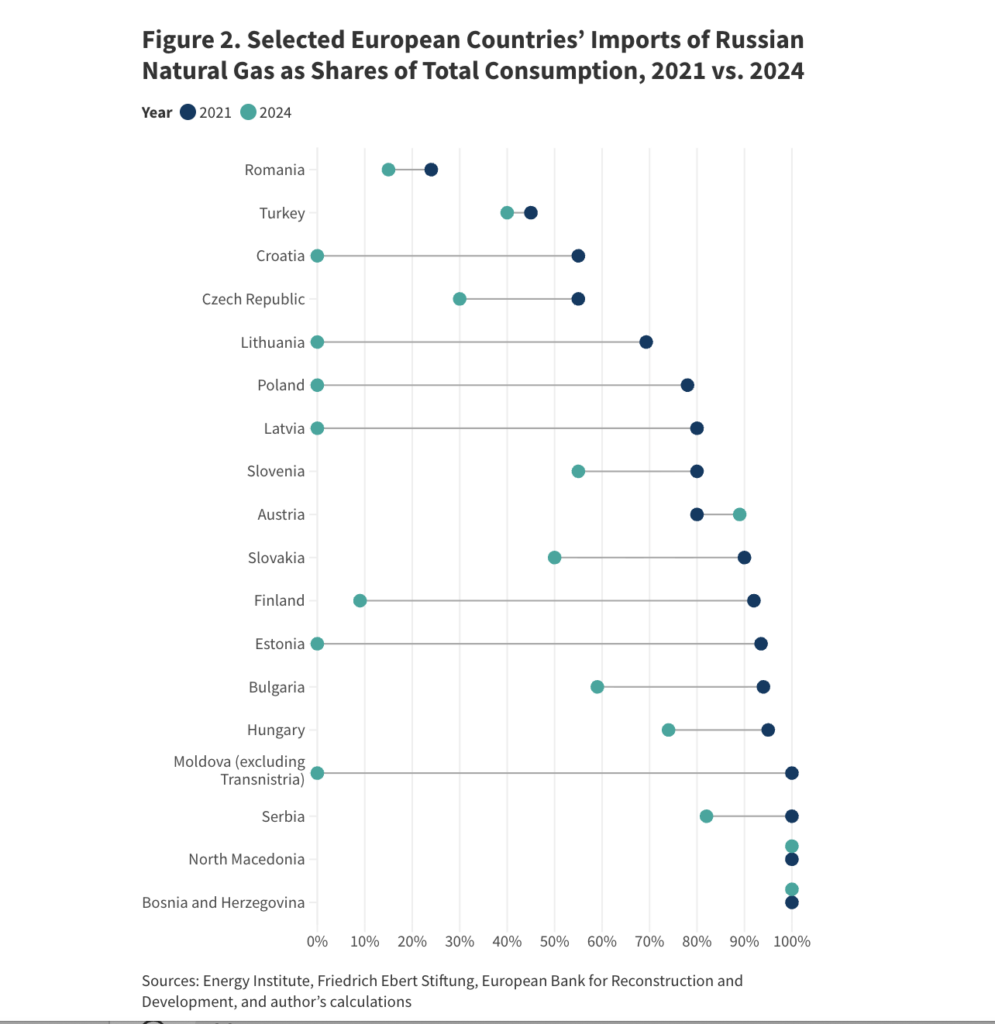

At the time of the invasion, only two countries in the region — Albania and Kosovo — were fully independent of Russian gas. Slovakia and the Czech Republic relied on Moscow for almost all of their imports. Bosnia, Moldova, North Macedonia, Hungary and Serbia were completely dependent.

Just two years later, in 2024, that number had risen to seven.

Russian gas supplies to Eastern Europe have dropped from an average of 80% to 37.6%.

It is a remarkable shift that many in 2022 thought impossible. The change was driven above all by Europe’s expanding capacity to import liquefied natural gas, with Turkey emerging as a key transit hub.

The transition has come at a high cost. And now, as ceasefire talks in Ukraine are being floated, some governments — including Hungary, Serbia and Slovakia — are calling for Russian gas to return.

But the fundamental shift has already taken place. Eastern Europe’s gas market will never go back to where it was four years ago.

That is the conclusion of Maximilian Hess, founder of the consultancy Enmetena Advisory, and a fellow at the Foreign Policy Research Institute and the International Institute for Strategic Studies. Below are his key points and arguments. The full article can be read at Carnegie Europe.

Eastern Europe’s initial dependence on Putin’s pipelines

For years, Russian gas shaped Eastern Europe’s geopolitics, binding the region to Moscow through pipelines such as Yamal–Europe via Belarus and Poland; the Blue Stream under the Black Sea to Turkey; and Nord Stream under the North and Baltic Seas to Germany.

In 2021, Russia supplied almost half of Europe’s gas — nearly twice as much as the second-largest supplier, Norway.

- Non-EU states Bosnia and Herzegovina, Moldova and North Macedonia were entirely dependent on Russian natural gas.

- Some EU members were almost as reliant: Slovakia and the Czech Republic imported nearly 100%, while Austria, Latvia and Slovenia got about 80% of their gas from Russia.

- Poland had begun diversifying as early as 2012, buying large volumes of liquefied natural gas. Yet in 2021 it still imported 78.3% of its gas from Russia.

- Lithuania and Estonia moved earlier. Lithuania launched its LNG terminal in 2014, slashing direct imports from Russia. Estonia invested in alternative energy and, in 2019, opened the Balticconnector pipeline with Finland.

- Finland, however, still relied heavily on Russian gas.

As a result, the Baltic states as a whole received around 74% of their gas supplies from Russia in 2021.

- Austria played a pivotal role in redistributing Russian gas, thanks to the Baumgarten storage hub on the Austrian–Slovak border.

- Hungary’s consistently soft stance towards Russia has long shaped its energy policy. After the invasion of Ukraine, Budapest actually increased imports from Russia, and after Ukraine halted transit at the end of 2024, Hungary switched to supplies via Turkey and the western Balkans.

- Serbia imported 89% of its gas from Russia in 2021 and remains just as dependent today, relying on the TurkStream and Balkan Stream pipelines. Belgrade doubled imports after the invasion.

- Bulgaria presented a sharp contrast. In 2021, it imported 94% of its gas from Russia, but has since shifted almost entirely to being a transit country, signing new supply deals with Azerbaijan after 2022.

- Croatia sourced 55% of its gas from Russia in 2021 — far less than in previous years thanks to its new LNG terminal.

- Of the region’s larger economies, Romania was the least dependent: Russian gas made up just 24% of its consumption.

- “Armenia and Azerbaijan join US AI projects as Georgia falls behind” — opinion

- Multipolar world: the US, China, Russia, SCO, BRICS and peace between Azerbaijan and Armenia

- Sewage in the Caspian: falling water levels expose Azerbaijan’s weak infrastructure

War, sanctions (and the lack of them) and the end of gas supplies

Eastern Europe’s move away from Russian natural gas imports after the February 2022 invasion of Ukraine was driven by several factors:

- expanded supplies from Azerbaijan,

- additional flows from Norway and Italy into Central Europe,

- and a rapid build-up of liquefied natural gas capacity.

Why did most Eastern European countries take on the costly and complex task of diversification?

Solidarity with Ukraine and concerns about national security played a role. But an even greater factor was Russia’s readiness to use gas as a weapon.

The sanctions gap

One important detail: the EU has still not sanctioned either Gazprom or Gazprombank.

Gazprom, Russia’s export monopoly for pipeline gas to Europe, has not been sanctioned by the US, EU or UK — even though Russian oil and coal imports were largely banned back in 2022.

In May 2022, Brussels set out a plan to end EU dependence on Russian energy by 2027. But instead of an outright ban, it focused on financing alternative energy sources.

All major Russian state-owned banks were quickly sanctioned after the full-scale invasion, but Gazprombank — which handles Russia’s gas trade — was targeted only by the UK in 2022. The US joined in November 2024.

As a result, the alliance still lacks a unified policy on Russian gas imports. What now blocks Russia from resuming exports to Europe is not law, but infrastructure.

The infrastructure problem

Three of the four Nord Stream lines remain ruptured on the seabed of the North Sea.

Ukraine controls the pipelines crossing its territory and, at the time of writing, still holds the key transit hub in Russia’s Kursk region for its second major route. This was made possible by Kyiv’s surprise counteroffensive in August 2024.

Other routes through Poland are unlikely to return, as Warsaw’s political elite remains united in rejecting Russian energy imports.

The chart shows how Russian gas imports fell as a share of consumption in individual European countries, comparing 2021 with 2024.

Lately, US president Donald Trump has been pressing Europe to stop buying Russian oil and to impose tariffs on countries that continue to purchase it.

- “Amid tensions with Russia, Azerbaijan should step up support for Ukraine”, experts in Baku say

- “Nationalisation of Armenia’s electric networks would collapse Russian influence”: Opinion

- Opinion: “Moscow and Tbilisi are discussing resumption of railway operations, ignoring Abkhazia’s interests”

The cost of breaking from Russian gas

The end of Russia’s dominance in the region has come at a heavy economic price.

European benchmark gas prices rose by an average of 163% in 2022. By 2025 they had eased somewhat, but remain high compared with 2021 levels, especially for households. Across Europe, the surge in gas prices triggered significant economic fallout.

Wealthier countries such as the UK, Germany and Switzerland drained public finances subsidising consumers and energy companies. In less affluent Eastern European states, price controls and support measures for households have led to mounting public debt.

Understanding how Europe managed to emerge from the crisis is crucial. It is a question of energy security, and of the ability to resist Vladimir Putin’s ambitions in Ukraine and the wider region.

New tools and routes

Eastern Europe’s shift away from Russian gas was made possible by two main factors:

- continental cooperation, particularly with partners such as Finland, Greece and Turkey,

- and the growth of the global liquefied natural gas market.

- Greece’s role

Greece has become a key import route for the region, and its importance is set to grow. In October 2024, it launched a regasification plant in Alexandroupolis, instantly doubling annual LNG import capacity to more than 10 billion cubic metres — 70% higher than the country’s total annual gas consumption.

But the driving force in meeting much of Eastern Europe’s LNG demand is Turkey.

Turkey’s role

The infrastructure running through Turkey and on to Bulgaria, Hungary, Moldova, Romania and the western Balkans is also used by Russia’s TurkStream and Blue Stream pipelines. And Turkey itself is a major buyer of Russian gas.

Even so, its central role in alternative supplies to Eastern Europe is undeniable, for several reasons:

- Turkey has five LNG import terminals — more than the rest of Eastern Europe combined.

- President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has pledged a sharp increase in Ankara’s domestic gas production in the coming years.

- Azerbaijani gas is shipped through Georgia to Turkey and on to Albania, Greece and Italy via the Trans-Anatolian pipeline (TANAP) and the Trans-Adriatic pipeline (TAP).

This third element has been the backbone of the EU’s diversification strategy, designed to bypass Russia well before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine. In July 2022, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen travelled to Baku to meet Azerbaijan’s president, Ilham Aliyev, and signed a memorandum of understanding committing both sides to doubling gas supplies from Azerbaijan by 2027, from 8.1 billion cubic metres that year.

In January 2025, Baku reported that deliveries to Europe had already reached 12.9 billion cubic metres in 2024. But doubts have been raised about the 2027 target, given Azerbaijan’s high domestic demand and declining output at the Shah Deniz field.

Poland and Finland’s role

In September 2022, the Baltic Pipe came online, bringing 10 billion cubic metres of natural gas a year from Norway. Polish pipelines to the Czech Republic and Slovakia carry those supplies further into Central Europe.

From Poland, the market is also linked to the Baltic states, which have benefited from access to Finland’s powerful Inkoo LNG terminal via the Balticconnector pipeline.

Romania’s role

Eastern Europe is expected to slightly increase its own production, led by Romania’s Neptun Deep project. Once operational in 2027, it is set to make the country the EU’s largest producer of natural gas.

What lies ahead

Expanded supplies from Norway and potentially Azerbaijan, along with future growth in deliveries from Turkey and Romania and the global LNG market, suggest that Eastern Europe can make its break with Russian gas permanent.

Gas prices remain high, and some governments — notably in Hungary, Serbia and Slovakia — are calling for Russian supplies to resume. In theory, Moscow could try to lure back European customers with steep discounts, but this remains unlikely. The way Russia used gas as a weapon in 2022 will not be forgotten in Eastern Europe anytime soon.

In March 2025, US president Donald Trump’s administration put forward a plan to ease sanctions on Russia as part of a possible ceasefire deal in Ukraine. But the White House cannot persuade or compel Ukraine or Poland to reopen transit, nor can it force Germany to repair and restart the Nord Stream pipelines. A large-scale return to Russian supplies is therefore improbable.

Turkey will remain a key player in regional flows, both for Azerbaijani and Russian gas. This raises the risk of new supply concentration, which should encourage Eastern European governments to expand their own LNG capacity.

The EU must keep investing in diversified infrastructure and local resources to avoid monopolisation. Only competition between suppliers and diversified routes can protect the region from the kind of vulnerability Russia exploited just three years ago.

Policymakers must also factor in that once peace is established in Ukraine, demand there will surge and almost certainly require new non-Russian sources.

Eastern Europe’s experience over the past three years shows that cooperation and diversification can succeed even under the most difficult circumstances — a lesson policymakers should keep front of mind.