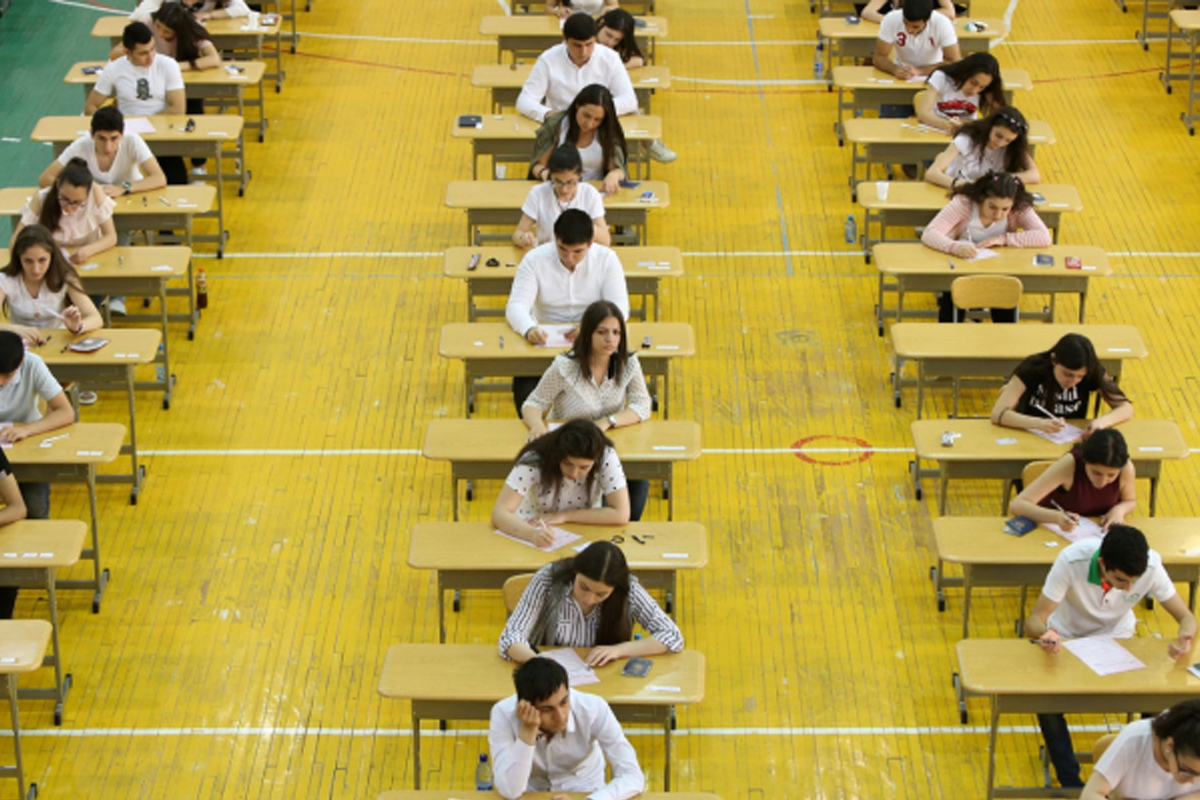

Thousands of vacant university spots in Armenia: What’s the issue and what needs to change?

Vacant spots in Armenian Universities

This year, over 5,000 university spots in Armenia remain vacant after entrance exams. Universities had expected 16,000 students, but more than 30% of the available places went unfilled, with some programs having no applicants at all.

What does this mean? Is youth losing interest in higher education? Why are there fewer applicants each year, and why are exam scores so low? We explore opinions from applicants and experts, and discuss potential solutions to the issue.

Applicant on the reforms

Victoria Mikaelyan, who successfully passed the entrance exams and is now enrolled in the Marketing Department at Yerevan State University of Economics, shared her thoughts on the recent changes.

Taking advantage of the reform allowing applicants to take only two exams, Victoria first focused on the English language test, which she completed in winter, and then prepared for the mathematics exam, taken in summer.

“The ability to retake entrance exams within the same academic year is a significant reform. It gives applicants a chance to test their skills twice, and the higher score is the one that counts,” Victoria says.

However, she is critical of another change: this year, applicants could list only one university and faculty of choice.

“Previously, we could choose several universities and faculties, but now this option is gone. I believe many applicants didn’t get admitted because of this.”

Victoria believes that applicants would feel more confident if they could list at least two universities for their chosen specialty.

“The removal of this option means many will lose a year, time, and money, leading to disappointment. Some may even give up on reapplying to university.“

Who’s responsible?

Opinions on the thousands of vacant spots in universities vary. Deputy Director of the Center for Evaluation and Testing, Karо Nasibyan, downplays the issue:

“There have been years when the number of available spots exceeded the number of graduates. Now, there are only 2,000 more spots than applicants. So what? Whether or not they are filled is up to the universities. If applicants come, great; if not, the universities will decide what to do next.”

However, Minister of Education Zhanna Andreasyan views the situation as unacceptable, given the repeated vacancy problem:

“This indicates that planning and allocation of spots were initially flawed. The government needs to change its approach to planning these spots.”

She believes that universities and the Higher Education and Science Committee should address the issue:

“Universities, in collaboration with the Committee, should plan spots realistically and strategically, especially for paid positions.”

Education expert Atom Mkhitaryan disagrees:

“This seems like shifting blame. Today, it’s the universities, but tomorrow, the blame might fall on the graduates, suggesting they don’t want to enroll. The responsible body is the ministry, so the problem lies with the ministry.”

Mkhitaryan notes that the number of applicants failing to meet the passing score is increasing annually:

“This indicates that the changes or ‘reforms’ in education are not yielding positive results.“

Vacant spots in Armenian Universities

Most and least popular majors

According to the Center for Evaluation and Testing, this year’s most popular majors were:

- Dentistry

- Public Policy and Management

- Political Science

- Law

- Public Relations

In contrast, there was little interest in educational and agricultural professions.

“As in previous years, there has been a decline in enrollment at agricultural and pedagogical universities. The situation at the Agricultural University is particularly severe, with only about 50 applicants in the initial round.

Pedagogical universities are faring somewhat better, but face a different issue. Many applicants who entered pedagogical programs chose a different specialization. Only 400-450 applicants nationwide pursued pedagogical professions, with some failing the entrance competition. As a result, there are many vacant spots in these fields,” says education expert Serob Khachatryan.

Experts explain the decline in applicants

Atom Mkhitaryan attributes the low number of applicants to insufficient attention to the field and low teacher salaries:

“Teacher salaries are a crucial indicator for any country and society. Education is essentially the foundation of everything. Countries that invest significantly in education see positive results across all economic sectors. Our teachers’ salaries are lower than in neighboring countries.“

Serob Khachatryan points to the switch to a 12-year education system as a major factor:

“With the shift to 12 years of education, students finish school at an older age. Many start working in the 11th grade, earning 100,000-200,000 drams per month (about $260-520), and see little point in spending four to five more years in university.”

He also cites the reduction in military service deferment spots for boys, increased tuition fees, and declining quality of school and university education:

“Specifically, the reduction in deferment spots has led to decreased interest among young men. Where previously half of the applicants were male, this number has dropped to 40% in recent years.”

Vacant spots in Armenian Universities

What should be done?

Serob Khachatryan suggests starting with improving the quality of school and university education:

“The Ministry should take steps to enhance the quality of school education, ensuring that students gain at least the basic knowledge needed for university admission. Universities also need to improve. The decreasing number of applicants is partly because graduates do not encourage their younger siblings to follow their path. If graduates are satisfied with their education, they will be more likely to recommend it to their siblings.”

Khachatryan emphasizes the importance of changing societal attitudes toward education and educated people:

“Educated people should be respected in the country. However, children see that educated individuals are undervalued, while shrewd and cunning, yet uneducated people are often praised. This affects the decisions of the youth.”

Atom Mkhitaryan advocates for increasing teacher salaries and fostering interest in pedagogical and agricultural fields.

He proposes revisiting a mechanism used in the past:

“The Soviet-era system of state-sponsored higher education worked well. The government could finance the education of a student from a village in need of an agronomist, provided they work in their village for a specified period after graduation. Currently, the state funds a number of high-achieving students but does not consistently utilize the potential of graduates funded by the state budget.“

Mkhitaryan believes implementing this mechanism would be particularly beneficial for rural areas:

“It seems the state pays for education but then fails to utilize the trained workforce effectively. What’s the point of planning free education spots if the investment in education does not lead to practical use of the trained graduates?“

Vacant spots in Armenian Universities