Seven hours in captivity

For two decades the Barsegyans have lived high up in the mountains, farming cattle. The couple live cut off from the outside world, in a wooden house they built for themselves.

Sirush Barsegyanexplains: “We have a radio and that’s all. There’s no TV, no electric light.In the evenings we have a kerosene lamp. We work to help our children – we make butter, sour cream and clarified butter. The boys come up once a week to collect what we’ve made to sell. After Seyran was taken prisoner, we stopped keeping the cows on the village pasture – it’s not far from the Azerbaijani positions and it was too dangerous.”

The scorching sun and wind of the mountains have weathered the 67-year-old’s cheeks and her hands are cracked from hard work. The house was built by her husband and contains everything needed for a temporary home, with a kitchen, bedroom and living room. In a corner of the kitchen the couple store home-made treats.

“We have 12 cows and Seyran and I milk them together. At the weekend our sons come up from the village to collect our produce and take it back down to sell”, says Sirush.

The Barsegyans have five children and 12 grandchildren. They live in the border village of Voskevan in Tavush Province, around 180 kilometres from Yerevan. The villageused to becalled Koshkota, which means ‘rugged plough’ in Azerbaijani. Picturesque Voskevan has a population of 1,400 and a 12-kilometre border with Azerbaijan.

On 18 August 1993 two residents of Voskevan, Seyran Barsegyan and Arto Grigoryan, were taken prisoner by Azerbaijani soldiers. Arto Grigoryan died in 2008. When Seyran recalls the abduction his voice and face change.

“I had gone to bring home the cattle. Suddenly, I was set upon by four men. They bound my wrists very tightly and then tied my friend to me, because his eyesight was poor. They put a rice sack over my head and dragged us away with them. When they took us towards the border my mind went blank – I realised this was the end, that I was being taken to my death. I couldn’t see anything. They took me to their headquarters, blindfolded and with my wrists bound.”72-year-old Seyran Barsegyan tries to remember every moment of what happened.

On Dzitank there is excellent pasture for grazing the cattle

He can still remember receiving blows to his head from an assault rifle, the beating and the humiliation he felt.

“Blood was drippingfrom my head. I kicked back at them;I was certain these were my last hours. My family and my wife just went out of my mind. Then they took us to a sheep shed. I thought that was where they were going to kill us. There was a huge dog tied up outside the door, but it didn’t even look at me.That seemed to enrage the Azerbaijani soldier. ‘Look’, he said, ‘Even the dog doesn’t bark at it’.”

The captured farmers were beaten again in the sheep shed. Later, when they were brought out again, one of the Azerbaijani soldiers came up to Seyran and addressed him by name, saying, ‘Is it you?’.

Seyran recognised the Azerbaijani – it was his old friend Amirkhan, who lived in the village of Paraklu in the neighbouring district of Qazakh.

“We embraced each other and became very emotional… If I met him again today, I would still embrace and kiss Amirkhan. We wouldn’t be here today if it wasn’t for him. We knew each other from the good old Soviet days. He hadn’t forgotten the hospitality we’d often enjoyed together. I worked in a garage in the neighbouring village of Voskepar. Not far from the garage there was a really good canteen. Back then there was none of this mess and Armenians and Azerbaijanis went to this canteen on an equal footing. We often had lunch together there”, recallsSeyran.

Seyran and his wife believe it was only by lucky fluke that their son, Meruzhan, who was with his father that day, wasn’t taken prisonertoo.

“Meruzhan was 17 years old. I took him out to the fields with me to look after the sheep and cows. My older son, Martik, had only just come back from the army and Meruzhan was wearing his uniform. That day I told Meruzhan to stay and watch the sheep while I went up the hill to get the cows and that’s where the Azerbaijanis captured me. If Meruzhan had gone to fetch the cows instead of me and I’d stayed to look after the sheep, he’d have been dragged off instead of me and killed. They’d never have released the lad. Amirkhan recognised me and that’s why I was released.”

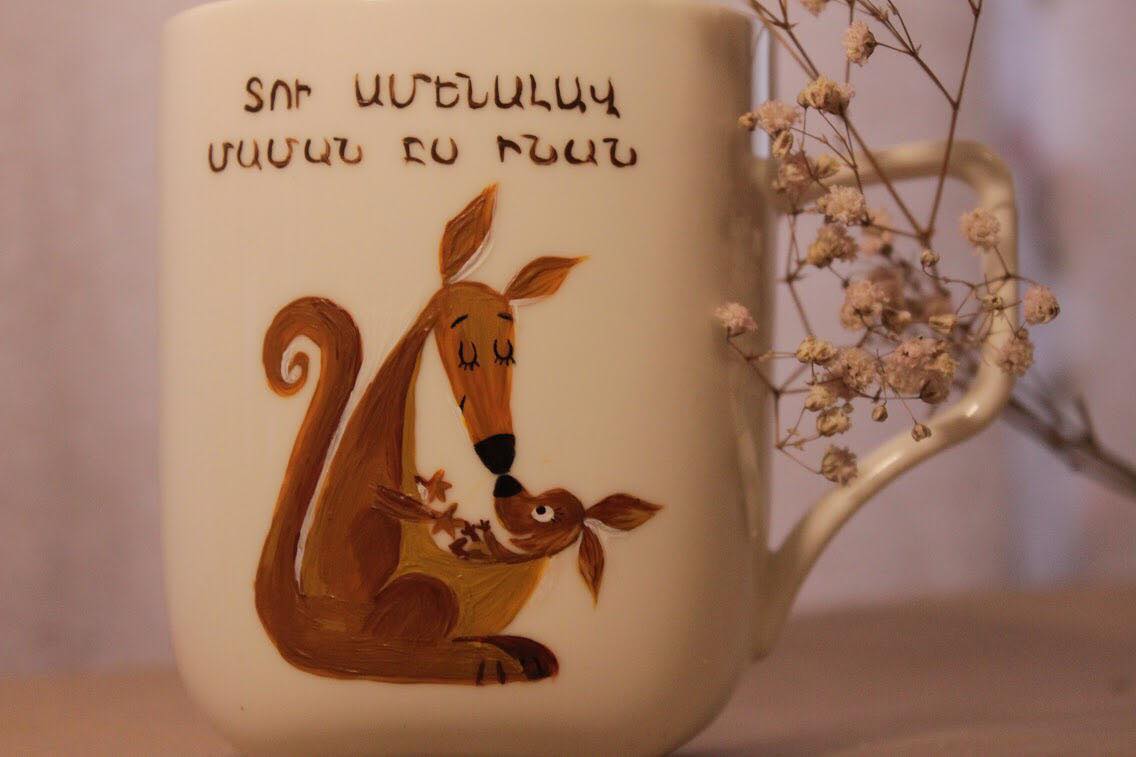

Sirush, known affectionately as Gushik (‘Dove’) by her husband, is agitated as she recalls how, when she heard about what had happened, her first thought was for her son.

“I thought, if he was with his father, let him at least be saved, but, thank God… What we went through was terrible. You can’t put it into words. I was without hope. But a miracle happened and Seyran came back too. The whole village gathered at our house to see Seyran who had managed to escape death. We celebrate all night.”

According to Seyran, when he and Amirkhan came to say goodbye on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan, Seyran asked to meet him there the following evening. He wanted to show his gratitude to Amirkhan for saving his life.

“I asked him to shoot into the air once he reached the place. Then I’d know he was giving a signal. I said I’d bring a sheep, vodka and wine and we’d have a fantastic meal by our spring, and our friendship would be even stronger than before. I really thought itwas possible. Amirkhan came that day and shot into the air, as we’d agreed. At that moment, as if to spite us, the alarm was sounded in the village, and there was an exchange of gunfire. They wouldn’t let me go up there, even though I was all ready for my meeting with Amirkhan. So we didn’t meet up again, but I’ll be grateful to him for the rest of my life”, concludes Seyran.