Op-ed: national interests of Armenia are an obstacle to peace agreement with Azerbaijan

Analysis of Armenia’s political environment in 2021

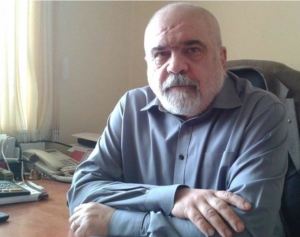

Armenia barely survived 2021 – a turbulent year filled with a number of acute political problems. There was unrest both within and outside the country, various formats of communication with neighbors were created, statements were signed with them, but, according to Armenian political scientists, no major changes took place. Political analysis of the results of last year and a possible alignment of the development of events from the political scientist, director of the Caucasus Institute Alexander Iskandaryan.

- PM of Armenia: There are no reasons for optimism, but we are trying to create them

- Pressure on Armenia: what does Baku want and what does Russia expect? Commentary from Yerevan

- ‘3 + 3’ or ‘3 + 2’։ New format for solving problems in South Caucasus

Political year in Armenia did not coincide with the calendar year

“It began in November 2020, with the end of the Karabakh war and ended with the resignation of the mayor of Yerevan and a big press conference of PM Pashinyan, talks about the Armenian-Turkish normalisation of relations process and the appointment of a special representative for negotiations with Turkey.

Everything that happened in 2021 within and around Armenia, from the point of view of foreign and domestic policy, as well as the economy, is a consequence of the military defeat in the second Karabakh war.

Among the special events of 2021, it is worth noting the December meeting of the heads of Armenia and Azerbaijan, which was the second after the November meeting of the troika [mediated by the President of Russia]. It formed a framework within which the foreign policy agenda of Armenia in relations with Azerbaijan, and de facto with Azerbaijan, Russia and Turkey, will be determined.

In general, from the point of view of the real foreign policy agenda, one cannot say that something significant has happened.

There were quite a few statements similar to the memorandum, but there was no serious activity following them, since, in reality, the interests of Armenia and Azerbaijan, Turkey and Russia differ greatly. It is impossible to reconcile them even regardless of the willingness and unwillingness of the counterparties. Their interests not only do not coincide, they are objectively opposed, and it is simply impossible to remove these obstacles”.

No new status quo

“Usually, after wars, agreements are signed, that is, a new status quo is formed, countries decide how they will continue to live in a new configuration.

For example, after a 30-year war, the Treaty of Westphalia appeared in Europe. After the Napoleonic Wars, the Vienna Congress appeared. After the First World War, there was the Treaty of Versailles. After World War II, the Yalta-Potsdam system was adopted.

There was a war, the situation “on the ground” has changed, but there is no agreement yet. There is no idea of how we will live in the future.

The old status quo is dead, but the new one has not yet been born. Scientists call such a situation “anomie” – the absence of norms.

The process of figuring out how we will continue to live is happening right now, and it will last for some time, maybe years, and in the form of various types of pressures, mainly on Armenia, but also pressures of the parties on each other.

What is interesting and important to us is pressure on Armenia. But along with this, there is pressure, for example, on Turkey. Turkey hoped to become the co-chair of the OSCE Minsk Group [the current co-chairs are the United States, France, Russia, who acted as mediators of the negotiations on the Karabakh problem before the 2020 war]. Apparently, this was promised to it, but the promise was never kept. Turkey attempted to participate in a peacekeeping mission with Russia in Artsakh, but also failed.

The pressure on Armenia is mostly consolidated. For example, Turkish and Azerbaijani policies towards Armenia are the same. They have common goals, and it is impossible to make this policy change.

This is a pressure system. It is applied in various ways.

- Discursive pressure. For example, at the presidential level in Azerbaijan, it is said that there is no Karabakh problem, the issue has already been resolved and Karabakh does not exist, therefore there is nothing to talk about.

- Diplomatic pressure, forcing Armenia to make some concessions.

- Pressure by military force. This is what happens on the border when the Azerbaijani Armed Forces invade and occupy the territory of Armenia.

All this leads to the rejection of the peace agreement. In reality, Azerbaijan does not want to agree on anything. It wants to win.

Azerbaijan wants to formalize the results of a military victory institutionally, to the maximum, to gain everything possible in this situation. That is why it is difficult to combine these interests.

I think that these processes will continue to be slowed down, a lot will not work out, some formats, commissions will be created, some memorandums or statements will be signed, but it will be impossible to get real changes under pressure”.

Armenia got ‘two Bakus’

“This also applies to the Turkish process. The process of normalizing relations has been initiated, special representatives have been appointed, their meeting is expected, but it is not worth assuming that a breakthrough will occur, or that and all problems will be resolved at one of the subsequent meetings, at least in the short term.

This process of building Armenian-Turkish relations is not new, it has been launched for the third time. Of these, only the “football diplomacy” [the initiative of Armenian President Sargsyan, who invited Turkish President Gul to a football match between the national teams of the two countries in Yerevan, after which the process of normalizing relations began] was more likely to achieve any results, and even then it failed.

This is an interesting phenomenon. With “football diplomacy” they tried to make the war of 2020 impossible or much less likely. It was an attempt to separate Turkish interests from Azerbaijani ones, to make Turkey be guided by its own interests, and not Azerbaijani ones. In this situation, the development of events would have been different.

But the process fell through, despite its extreme seriousness and the involvement of the US Secretary of State, the Russian Foreign Ministry and European representatives in it. It failed because of the Azerbaijani lobbying in Turkey.

Today Armenia and Artsakh have two Bakus instead of Ankara on the one hand and Baku on the other. Turkey is pursuing the same policy towards Armenia as Azerbaijan. They have been brought together, and it is absolutely impossible to change this, at least in the near future”.

Nagorno-Karabakh is a center of political identity

“Until 2018, all the changes of power in Armenia took place under the slogans and with the help of the rhetoric of the national agenda, in particular, the Artsakh problem. Nagorno-Karabakh has always been the center of political identity.

The coming to power and resignation of Ter-Petrosyan [the first president of Armenia, elected after the country’s secession from the USSR – 1991-1998], the coming to power of Kocharyan [the second president of Armenia – 1998-2008], the coming to power of Sargsyan [the third President of Armenia 2008-2018] and his departure – all this was linked with the Artsakh agenda.

In 2018, for the first time in the history of independent Armenia, people came to power who did not raise the Artsakh issue either during the Velvet Revolution or during the elections.

They talked about corruption, social injustice, everything was built on one “social issue”. But now the rhetoric against Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan is once again building on the Artsakh problem. The opposition accuses Pashinyan of varying degrees of expressiveness in betrayal on the Karabakh issue, bearing in mind the interests of Armenia”.

Back to square one

“The resistance of the opposition political forces to the ongoing processes is obvious.

As for society, we see its apathy. The main support of the regime today is not the support of the people, but their apathy towards politics.

About half of the voters went to the elections [early parliamentary elections were held in June 2021 to resolve the internal political crisis after the defeat in the Karabakh war]. Of these, 20% voted for parties that did not have a chance to get into parliament. This was a pure protest vote.

People no longer wanted to give their vote to Pashinyan, but they were not ready to give it to Kocharyan, that is, the “former government” – and these moods were defining.

We are returning to the configuration that existed before the revolution, when under the ‘one and a half party system’, one party determines the decision-making process as a whole, and for this, it does not need opposition in any way. This is the legacy of Serzh Sargsyan. He left Nikol Pashinyan or any future government with a “brilliant” constitution.

This is a classic hybrid regime, when there are opposition forces in parliament, they have the opportunity to speak, protest, there is pluralism of the press, but this has almost no effect on decision-making. That is, the structure of our ‘one and a half party system’ and the structure of a weak government and a weak opposition have been restored.

In addition, weak legitimacy of the authorities was restored. In Armenia, a weak government existed from about 1992-93 to 2018. The authorities got used to this, they found options for existence in such a regime, took alienation and the fact that they were not loved for granted. For example, when he came to power, Serzh Sargsyan was already unpopular, but the authorities existed in this environment and developed mechanisms for it.

Pashinyan’s Civil Contract party came to power with insanely high popularity, and this was their only tool, and they used it to do whatever wanted in parliament. Despite the presence of the Republicans [Republican Party of Armenia – the ruling party before the 2018 revolution] in the National Assembly, they managed to hold early elections, etc. But it is over now.

Now revolutionaries have to learn to live with low popularity, despite the fact that a significant part of the people rejects them.

Everything returns to normal and perfectly illustrates the well-known thesis in political science that it is impossible to change the situation simply by changing some people. The structure does not change, institutions, political culture, etc. do not change with the replacement of bad guys with good ones.

However, the history has proven that this does not last forever. Such a system leads to upheavals, rotation of power, and changes. This was the case with the communists, Levon Ter-Petrosyan, Robert Kocharian, and with Serzh Sargsyan.

The problem for Armenian leaders has always been the misconception that their rule can go on forever – and the current authorities are no exception. Discontent and apathy will grow, and at the climax there will be some political force that can pick up this discontent, as Pashinyan did in 2018.