Neither dead nor alive

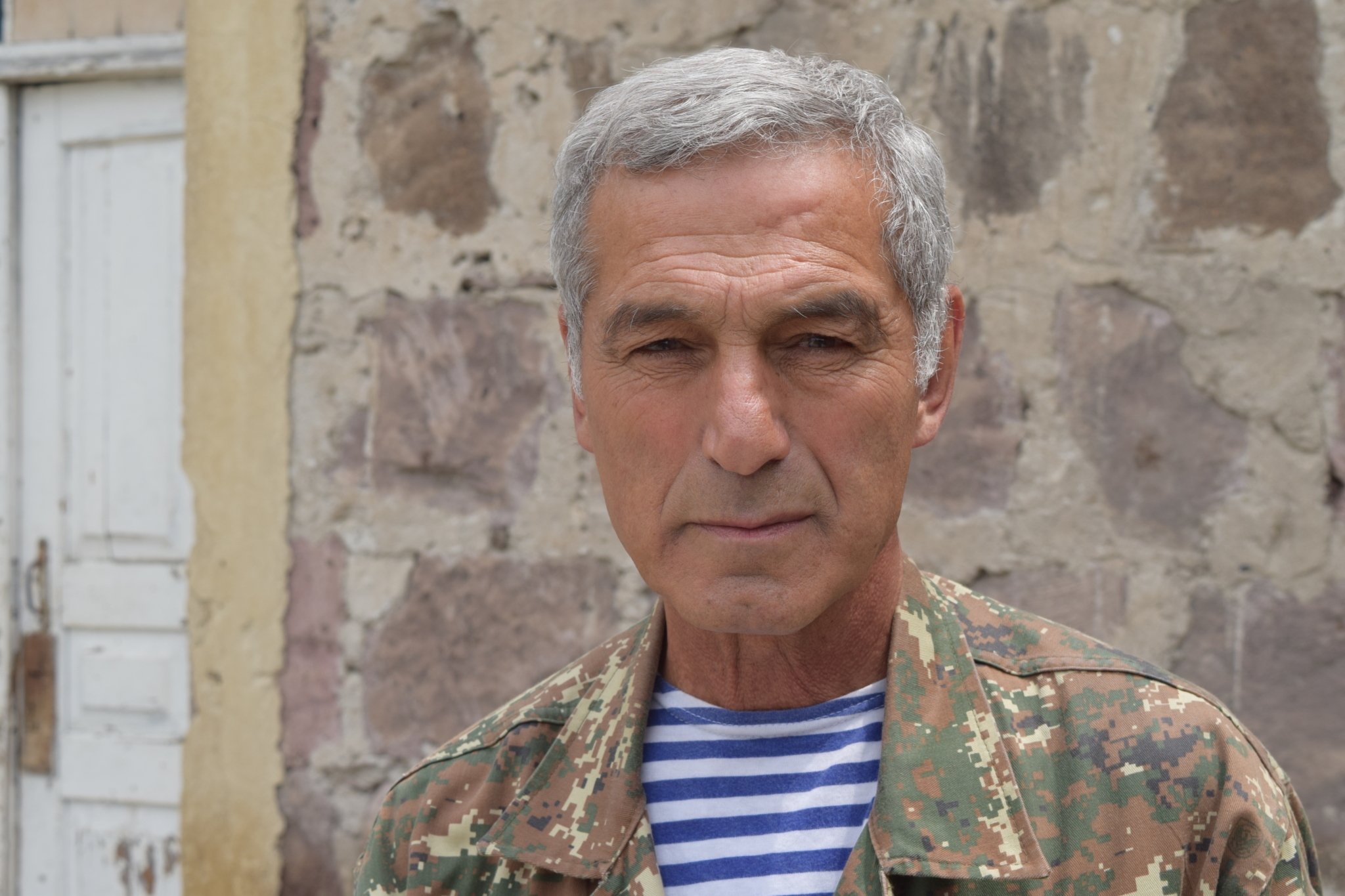

Grach Abraamyan, who lives in Armenia, sees his life as divided into two parts – before his imprisonment and afterwards. Having been taken prisoner by the Azerbaijanis during the Karabakh war, he was believed to be missing, presumed dead. He returned home to discover that his grieving family had laid him to rest in a military cemetery, unaware that he was still alive.

Twenty-seven years after his imprisonment, Grach Abraamyan, accompanied by army comrades, family or grandchildren, goes to the Yerablur military cemetery every week to pay his respects to friends who were killed.

The war over Nagorny Karabakh began in the early 1990s and today remains an unresolved conflict, hindering the development of the South Caucasus.

A ceasefire was signed in 1994 but the conflict still continues to claim lives.

According to data from researcher and journalist, Tatul Hakobyan, during the Karabakh war and the period between 1994 and 1997 the Armenian side lost over nine thousand people.

Grach was taken prisoner on 19 May 1991. He had been taking part in military intelligence-gathering operations during which he was captured in an Azerbaijani village near Armenia’s Tavush province.

He was in detention for four days but didn’t return home until three months later, on 30 August 1991.

Sixty-six-year-old Grach recalls that day: “I remember knocking on the door. My father-in-law opened it and just stared at me in astonishment. I went inside and the children ran over to me but my wife was just frozen, looking at me. She couldn’t speak. Then I glanced at the TV and saw a photo of me in a black frame, with candles burning next to it. I asked my wife, ‘What’s that?’ She told me, ‘We buried you.’ ‘What do you mean, you buried me?’, I asked, flabbergasted.”

Grach’s wife, Alvard Abraamyan, says: “When Grach came home I felt as if I was dreaming. I stroked his face and hands to convince myself it was really him. Then I looked to see if he was wounded and asked in amazement, ‘You’re alive?’ I couldn’t get my head round what had happened.”

The next day Grach and his army comrades and family went to visit his grave.

“I saw that they’d dug a grave for me at the Yerablur cemetery, the earth was piled up and a metal plaque had been put up. It said, ‘Grach Abraamyan, born 1952, died 1991’. When we saw it, we started laughing. My army comrades started joking, saying ‘Look, Grach is dead – we must be totally out of the loop’.”

Later, in 1992, Grach used the grave, which had been intended for him, to bury his friend, Grant Asatryan, who had been killed in the war.

According to data from the International Committee of the Red Cross (ICRC), during the period of the Karabakh conflict over 4,500 people, both military and civilians, from Armenia, Nargorny Karabakh and Azerbaijan, have been registered missing. In 2015 the ICRC presented the parties in the conflict with an updated missing persons list.

In 2014 the ICRC began collecting biological samples from relatives of the missing. So far 778 biological samples have been collected from the blood relatives of 298 missing persons, and 195 of these samples have been quality controlled and used to generate DNA profiles.

Karabakh war veteran, Grach Abraamyan, was born in Baku to an Armenian family. However, following the death of his mother, he was sent to Karabakh at the age of four to live in a children’s home in Shushi. He recounts that his father had remarried and he had been left in the care of his grandmother. After eight years in the children’s home in Shushi, he returned to Baku and continued his schooling at a residential school before being called up into the Soviet army.

Grach speaks Azerbaijani and when he was taken prisoner in 1991 the first thing the Azerbaijanis did was to try to establish his identity.

“They forced me to confess I was Armenian, then when they took off my clothes they saw the tattoo on my arm that says ‘Love my Alvard’ in Armenian. They realised I was Armenian and I immediately felt a heavy blow to my back. That’s the last thing I remember before I lost consciousness”, recollects Grach.

While he was imprisoned he was repeatedly beaten and ended up with numerous wounds and fractures. Although the visible traces are long gone, the memories are still very much alive.

“I remember one time one of them brought bread. He threw it on the ground, trampled it with his foot and then swore at me and ordered me to eat it. I thought, if I eat it, he’s going to beat me, but if I don’t eat it, he’s still going to beat me, so I decided to eat it, as I was dying of hunger. I’d barely started eating the bread when he kicked me in the neck. After that I couldn’t speak, because my vocal cords were damaged.”

On the fourth day Grach asked to be taken to the toilet and managed to escape.

“When I came out of the toilet, I saw that the Azerbaijanis were involved in a loud conversation and weren’t looking in my direction. I decided to run away. My legs were so weak, my face was disfigured, my throat was damaged and my eyes were swollen and I was covered in bruises, but I ran. They didn’t see me so I ran and found an old toilet about 20 metres away. I climbed in and hid, up to my neck in excrement.”

He stayed there for several hours, waiting for the sounds of the voices of the people looking for him to subside. He then spent the whole night walking through the forest and at sunrise he reached the Armenian side.

“Life is very precious. When they beat me in prison I thought I was going to die, but I wanted to live to my very last breath and I never gave up. After I escaped, when lots of people heard my story they asked me how I had endured being in that toilet, covered in excrement – how could I stand the smell, hiding there for four hours? But I got through those four hours for the sake of life, in order to live, every second was precious to me. At that moment I thought, I might starve, I might not live well, but I just have to endure this so I can go on living.”

Once he was back in Armenia, Grach spent three months in hospital in Ijevan. At one point during that time his wife received a phone call to tell her that Grach was close to death.

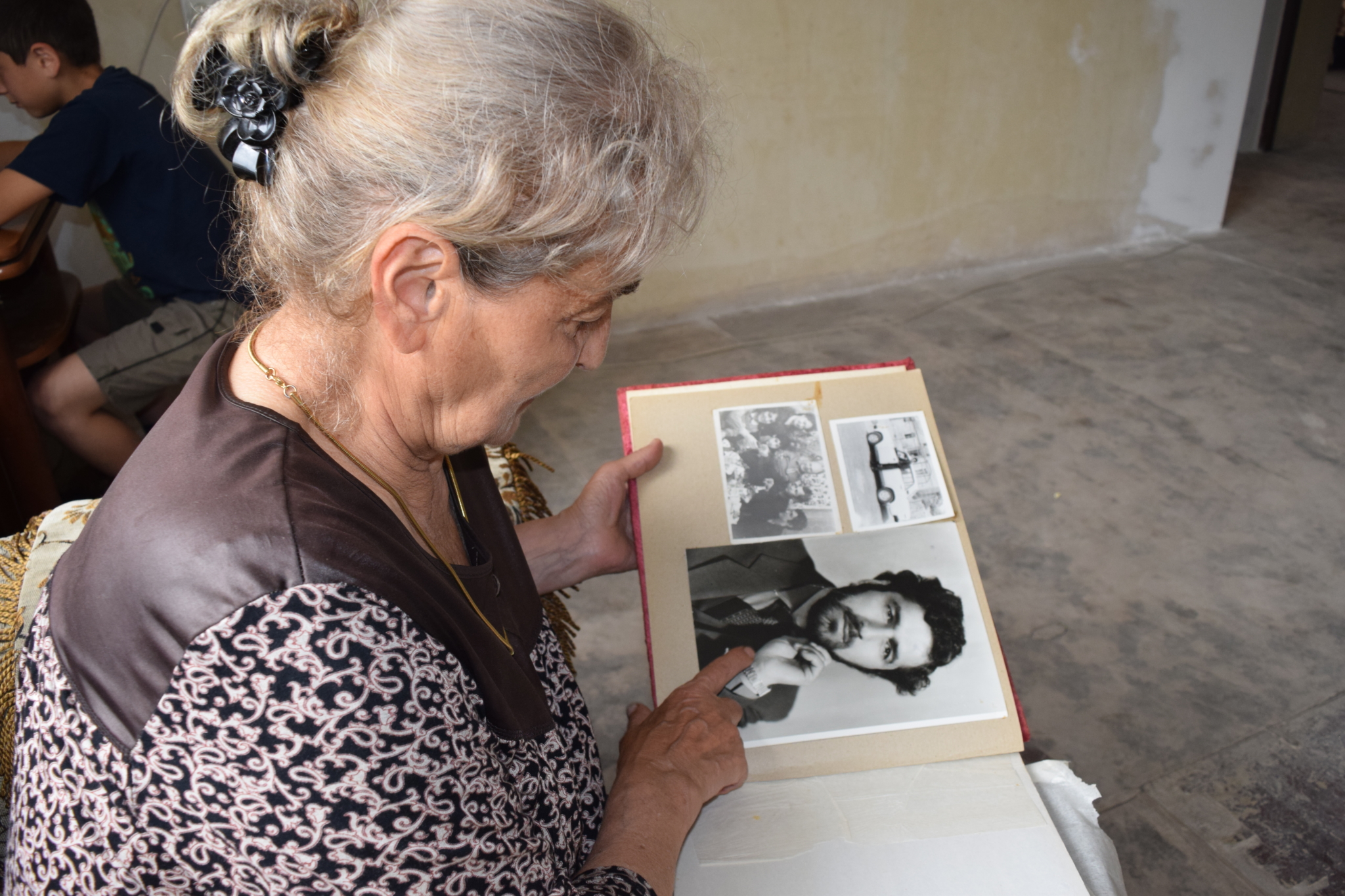

“When I got the message I immediately fainted. I thought my husband was in one of the Yerevan hospitals and the family started looking for him in all the hospitals and morgues of Yerevan. But my husband’s body was never found”, explains Alvard. “Days went by and there was no news and the neighbours started saying Grach was a traitor, that he’d gone over to the Azerbaijanis and wasn’t coming back. My children stopped going to school, they spent days crying and feeling ashamed that their father was being called a traitor. The family decided we should have a grave for Grach because they thought he’d been killed. On 18 June, a month after he was imprisoned, we dug a grave for my husband at Yerablur and buried his clothes and shoes in it.”

Grach explains that he was not conscious for the three months of his treatment. He had multiple fractures, his vocal cords were damaged, he wasn’t even able to speak to make contact with his family. Only once he was better was he able to return home to Yerevan.

“I saw a lot of terrible things on the battlefield. I lost close friends, saved the life of a wounded comrade, rescued an Armenian from captivity and saved the life of an Azerbaijani child. I don’t want war, God forbid there’s another war. Anyone who’s been through war knows what a tragedy it is”, says Grach.

Now he works as a security guard at one of Yerevan’s new housing developments and in his spare time he works in his little garden at home. Grach lives in the village of Azatashen with his wife, son and grandchildren. He says he worked mainly in construction after the war

“There’s a saying – ‘neither dead nor alive’. I often feel like that… Obviously, I’m alive, I walk about, I breathe, but I haven’t found a meaningful place for myself in society. The traces of the war will stay with me to the end of my days. I want peace.”

Unheard Voices is part of International Alert’s work on the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. It is the result of work produced with journalists from societies affected by the conflict and their collaborative efforts to highlight its effects on the daily lives of people living in the conditions of ‘no war, no peace’. The purpose is to ensure their voices are heard both at home, in their own societies and on the other side of the conflict divide, allowing readers to see the real faces hidden behind the images of ‘the enemy’.

This project is funded by the European Union as part of the European Partnership for the Peaceful Settlement of the Conflict over Nagorno-Karabakh (EPNK).

The materials published on this page are solely the responsibility of the journalists and do not necessarily reflect the opinions or policies of International Alert or its donors. All our journalists adhere to a Code of Conduct, which can be found here.