Changes to Azerbaijan’s Law on Information could become tool for repression

Changes to Azerbaijan’s information law

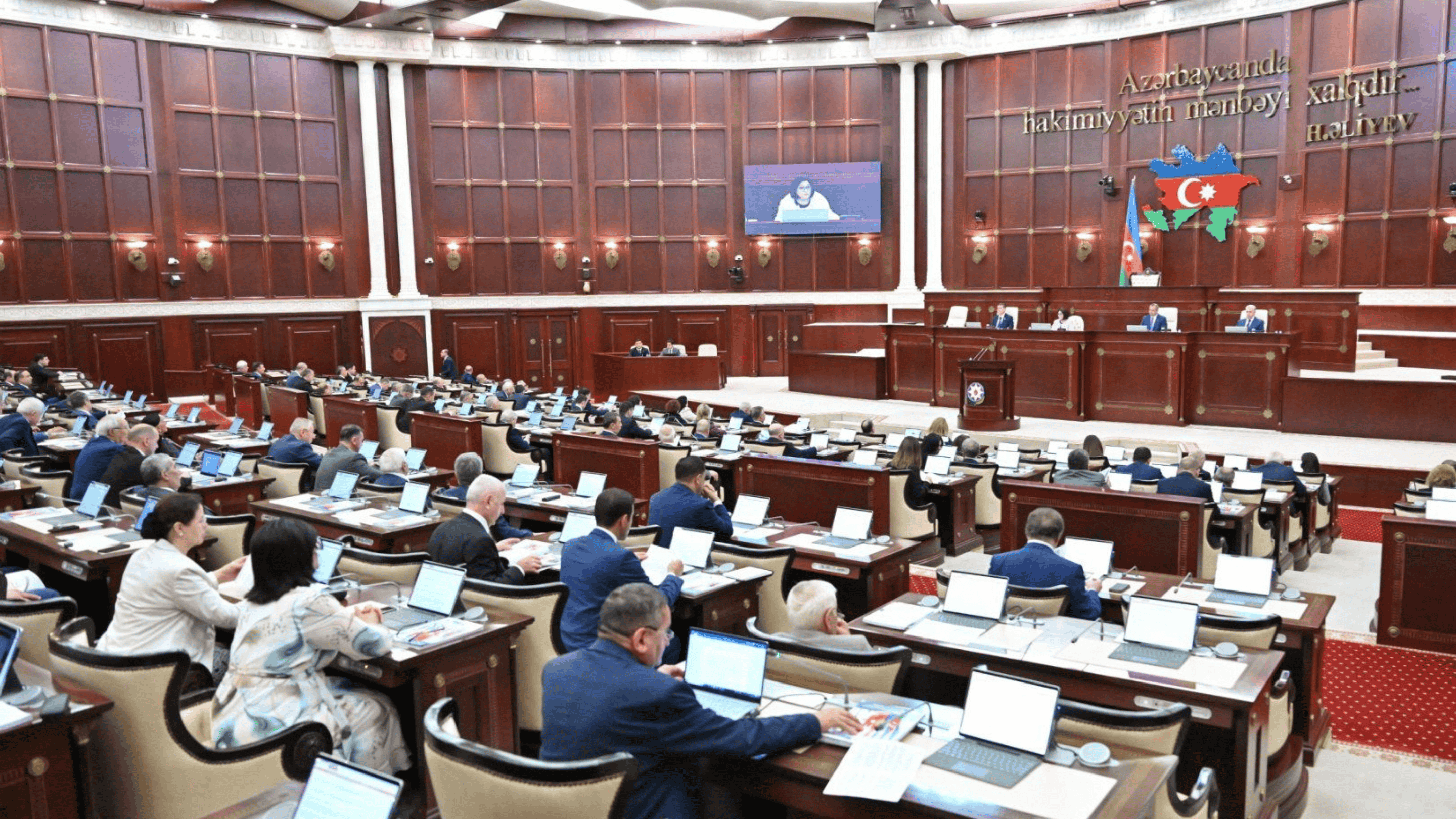

Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev has approved amendments to the Law on Information, Informatization and Information Protection, previously adopted by the country’s parliament.

Under the changes, the distribution on internet platforms — including websites and social media — of content that “openly expresses disrespect for society and insults public morality” is banned. The amendments are said to aim at preventing the spread of such material and at “protecting national moral values and ethical standards”.

Key provisions of the amendments

The new legal provision bans the dissemination on online resources and information and telecommunications networks of actions that offend public morality and openly express disrespect for society. This includes obscene language, gestures of a similar nature, as well as the display of body parts in a manner deemed contrary to national moral values.

The explanatory note to the bill says that unethical publications, calls and offensive actions have become increasingly widespread on social media and websites in recent years, making such regulation necessary.

It also stresses that this type of content has a particularly negative impact on teenagers and young people and may influence changes in their patterns of behaviour.

The amendments further provide for a clearer definition of enforcement mechanisms and liability, aimed at addressing existing gaps in this area.

The law applies not only to internet users, but also to owners of information resources and domain name holders. As a result, platforms themselves will be required to comply with the new rules.

Expert warns of potential risks to freedom of expression

Osman Gunduz, president of the Azerbaijan Internet Forum (AIF), says the absence of clear definitions in the law for concepts such as “public morality”, “obscene language” and “contrary to national moral values” increases the risk of broad and subjective interpretation.

“President Ilham Aliyev has approved new amendments to the law that had been discussed for a long time. Under the changes, the dissemination during mass events of content that offends public morality, openly expresses disrespect, contains profanity, obscene language and gestures, as well as visual material deemed contrary to national moral values, is restricted.

Why was this step taken?

It can be assumed that in recent years the growing spread on social media and certain online platforms of content that clearly goes beyond ethical boundaries — offensive, explicit and aggressive in nature — has made such legal regulation necessary. From the perspective of protecting children and vulnerable groups, as well as ensuring minimum ethical standards in the public space, the stated aims of the law appear understandable and logical,” he says.

However, it should be noted from the outset that there are also risks involved.

Because the concepts used in the law — such as “public morality”, “obscene language” and “contrary to national moral values” — lack clear definitions, there is a risk of subjective and selective enforcement.

For example, if the actions of an official are subjected to harsh and emotional criticism on social media, such a post could be interpreted as “open disrespect for society”, removed, and its author held liable.

The same approach could be applied to widely shared satire, performance art, video footage from public protests, and journalistic material.

The message to journalists, bloggers and content creators is clear: greater caution will be required when criticising. The use of profanity, explicit insults and provocative visual material already creates legal risks and potential liability. Live streams and “stories” will carry the same responsibility as standard publications.

It is important to understand that in the online environment, profanity, nudity, actions aimed at humiliating society and open insults are no longer treated as forms of freedom of expression. Criticism based on facts, arguments and adherence to ethical standards remains safer.

In principle, the law is intended to protect the ethical environment and public space. However, without clear guidance, unambiguous interpretation and effective judicial oversight, its application may pose risks to freedom of expression. Similar approaches exist in a number of countries, but they are applied within narrow limits, with clear definitions and under court supervision.

Experience shows that where democratic traditions are weak, institutions are underdeveloped and officials act arbitrarily, such provisions can turn into tools for suppressing journalists, civic activists, bloggers and critics.

I believe the new rules have the potential to raise the standard of content production in the country, encouraging higher-quality, well-argued and ethical material.

There is hope that the new regulations, aimed at protecting the public space, “public morality” and national moral values, will genuinely contribute to a higher level of public culture and will not become instruments of self-censorship or the silencing of critical voices.

Changes to Azerbaijan’s information law