Share

Most read

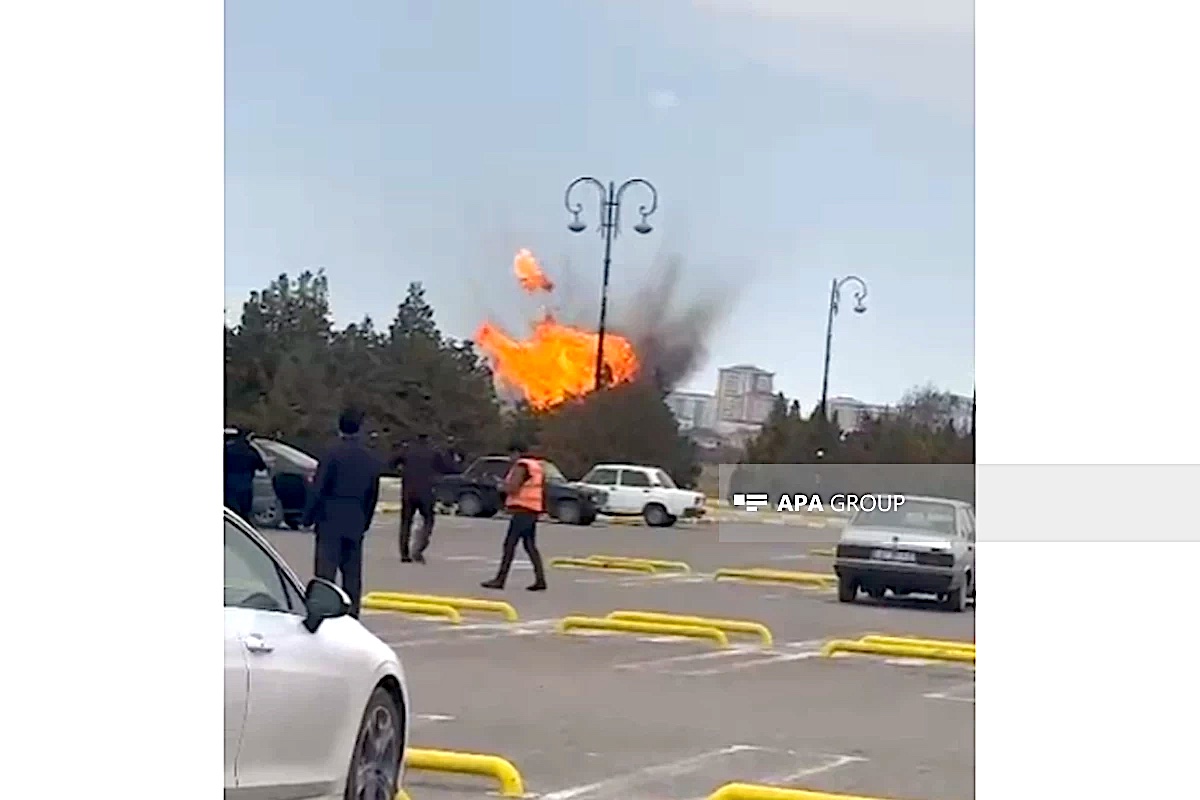

Drone attack on Azerbaijan: authorities blame Iran, experts consider other possibilities

Opinion: 'Possible influx of refugees from Iran poses Armenia’s biggest challenge'

Latest news in Georgia, Armenia, Azerbaijan, summary. Live

Ukrainian drone shot down in Abkhazia, no casualties reported

Opinion: US will remember Georgian government’s stance on events in Iran

Georgia’s State Security Service probes authors of studies on Iran’s influence

'Forced to kneel, humiliated': Georgia ordered to pay compensation to children from Ninotsminda boarding school

EU commissioners: 'Georgian Dream undermines long-term partnership with EU'

Visa-free travel to EU for holders of Georgian diplomatic passports officially revoked

State Department: 'US reviewing what steps Georgia could take to deepen ties'