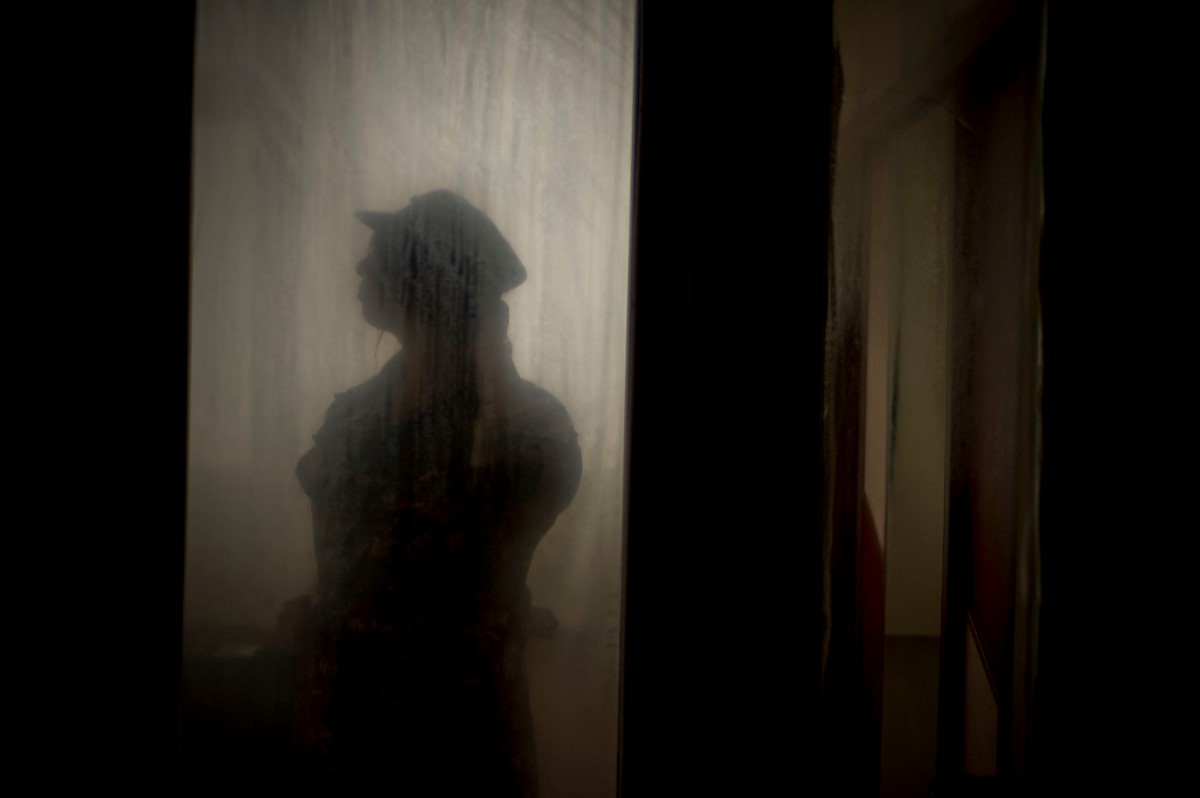

Stories of three women from Karabakh – in war and peace

From 1988 to 1994, 200 women from the Armenian side of the conflict participated in the Nagorno-Karabakh war, 42 of whom died on the battle field. Information on female fighters in the recent April 2016 escalation of fighting has not yet been brought forward. However, there is data that shows that, after the Four Day War of April 2016, the number of people who want to receive a military education has practically doubled.

First war: Doll Babo

It takes six hours to travel from Yerevan to the Karabakh town of Shusha by car. The driver took an earring and a small blue flower out of his pocket.

“Ten days ago I drove a family to Karabakh, and a small girl was among them. This is her ring. I keep it in my pocket in the hopes that I meet them again so I can give it back,” he says.

I don’t know if he has found the owner of the earring or not. I went there to search for another “belle” – Evgenya Arustamyan.

Everyone in Shusha knows Evgenya Arustamyan. She now has a finely wrinkled face and short greying hair, though she used to be the beauty of the town. She is known as Babo [grandmother] now, but people still call her Doll.

Photos: Nazik Armenakyan

Her home is large, airy, and very clean. So clean it looks as if she is waiting for guests.

• Azerbaijani president, Armenian PM agree to decrease tension on Karabakh line of contact

• Armenian MFA: “The alternative to peace in Karabakh would be a disaster”

Next to the TV are two photographs – she is in one of them, at 16 years of age. The other photograph is of her son.

“This is Armen, my younger son. Look what pretty eyes he had. He died two years ago,” says Babo.

The loss of her son has been very difficult for her to cope with. She believes that the investigation that was done didn’t take all the factors into account. She struggles to come to terms with the fact that is not the war, but an accident that took her son away.

In order to change the topic I asked: “Babo, did they used to fall in love with you often?”

“No,” she says, “they were afraid of me. I was very sharp and direct. There was a boy I liked, but I married without love, and so did he. That’s life.

“There was no democracy at the time, and my husband was my ‘master’. My mother had already passed away, and no one was there to help me. I was working and my three sons grew up. The older sons were crippled by the war – they both had combat wounds. One left for Russia, to Leningrad [ed. St Petersburg], and didn’t come back, but the other is still serving. After the death of my husband, Armen and I remained here alone. Everything you see in this house was made by him, but he never got to enjoy it,” said Babo, wiping down the wet door of the washing machine.

She does this after every load. The washing machine was a gift from Armen, so she won’t allow it to break down.

Photos: Nazik Armenakyan

In 1992, two of her sons went to the front as volunteers, as did her four brothers. Babo said that it was the year the ‘women squad’ was formed.

“There were 12 of us in the squad. We shared a sniper rifle and several automatic guns. I was the sniper. On the night of 23 August 1992, we carried out an operation near the village of Kubatlu. We lost one of our girls that day, and two were injured – one of them me,” she said and pulled up her skirt to show her scar – a rough line zigzagging all the way from her knee to her chest.

“We would fight for three days, and then go home for three days – to cook, to clean, and to take care of the injured. I tried to help them – what else was there to do? I had two soldiers at war too.”

Knowing that we were going to drop by the military outpost, she gave us a box of cookies and candy, and a bag of herbs, which she has collected herself to use for tea. We were to pass it on to the soldiers there.

Photos: Nazik Armenakyan

Second war: Narine

I looked at Narine – a petite, smiling student who has been to the war. We went together to her home village called Nerkin Karmirakhbyur in the Tavush district of Armenia. It is possible to see the Azerbaijani positions with the naked eye from this village.

I looked at Narine and thought: “How could she have carried a weapon around her shoulder? Surely the barrel reached below her knees.”

“See here, this is a unique vehicle. It has two roofs – a main one, and a temporary one. In the main one, there is a hole from a projectile. We cover it up with the temporary roof in order to protect the car from rain and snow. My father goes with this car to the vineyards to gather the harvest. Our gardens are right underneath the Azerbaijani positions. The snipers probably already know our car – red with a big hole in the roof,” said Narine when we got to the village.

The day the April 2016 war broke out she told her family she was leaving for Karabakh to join the fight as a volunteer.

Photos: Nazik Armenakyan

“What we know about the people on the other side of the border we learn from books alone. I remember that, as a child, I used to think that Turks were something wild and terrifying, not really people. When we realise that the people over there are just like us, that they have the same dreams and fears – then something may start to change,” said Narine.

Light almost doesn’t make it through the bedroom window – her father has barricaded it with a large stone because the window can easily be seen from Azerbaijani positions. Several times snipers targeted it. One bullet is still stuck in the window frame.

But Narine hasn’t moved her bed.

“Two years ago, in August, when the situation was very tense, people tried to make things safer, at least for their children. But my parents couldn’t get me out of the house. I knew that if I were to go out of the home, I wouldn’t return because I would be ashamed.”

Photos: Nazik Armenakyan

“Nar, can you imagine peace?” I asked.

“Peace? A day without shooting, without victims – that’s the closest we can come to peace,” she says. “I would like for this issue to be resolved by peaceful means, through negotiations. The problem is that people don’t know what the negotiations are for.”

The next morning, in addition to the smell of hot tea and baked potatoes, Narine sprouted a smile – her friend has given birth to a girl. Now peace for Narine is even more important: the weight of this new-born girl has been added to the weight on her shoulders.

One more war or peace: Eva

Eva was the first girl to be admitted to the military academy in Stepanakert. It was two years ago. Now she is the pride of the academy.

“I always wanted to be a military lawyer. However, it turned out that girls couldn’t study for it neither in Armenia nor in Russia. So I ended up going for air defence,” says Eva.

She is the only girl in the academy whose parents were not against her choice. Her father and her uncles were all military men.

“I’ve never seen peace. We live on the border: some days are good, some days are bad. We are always on alert.”

“During the April war [in 2016] we heard daily about those who were injured and those who lost their lives – kids my own age, a year or two older. It was horrible. One day, we organised an event to honour the memory of the academy graduates who had lost their lives. I had a photograph of one of them in my hands. After the event, his mother came up to me, hugged me and cried. I didn’t know what to tell her,” recalled Eva.

Eva carefully put her awards in a folder – one for good singing and another for sports achievements. She put on a large coat and walked outside. The bus stop is right next to the academy. They are already used to seeing this petite girl in her military uniform, and have long since stopped being surprised at the sight of her. Several minutes later, she was home.

Her mother and sister were waiting for her at home. Her father was still on his duty on the border.

“Eva, what are you studying for? For war?” I asked.

“I’m studying to be ready,” she said. Then she added:

“I hope I’ll never have to put this knowledge to use. I don’t want war. But politicians and lawyers have been struggling to solve this issue for over two decades now. This war is older than me,” said Eva.