A reflection of the Karabakh conflict in literature and film

F

rom pathos and hatred to humanism, from propaganda of universal values to patriotic enthusiasm, from enmity to pacifism, from battle victories to human tragedy: the Nagorny Karabakh conflict is reflected in the most different ways in the Armenian art. Thousands of poems, features and documentary works have been published, over 100 feature films and documentaries have been produced and 4 performances have been staged in Armenia since the start of the war in Karabakh in 1991. Despite the 1994 ceasefire agreement between the warring sides, the unresolved conflict continues to take human lives. Military clashes that started on the night of 2 April 2016 and continued for four days were unprecedented in scale. In Armenia, these events are referred to as the ‘Four Day War’. Hundreds of victims on both sides, a growing distrust and hostility, and new human tragedies build a bigger barrier between Armenians and Azeris. After the ‘April War’ in 2016, the Karabakh conflict once again became a burning issue in Armenian cultural life.

Feature films

During 25 years of independence, Armenian cinematography has produced a number of films related to the Nagorny Karabakh conflict. The scenes of these films mostly reflect the historical events of the conflict, bolster patriotic sentiment, present losses and encourage victories. In 2016, Director Mher Mkrtchyan presented his feature film Life and War. In the words of the film makers, it is dedicated to the “heroes who fell for the liberation of Artsakh [Nagorny Karabakh]”.

The film tells the story of four 25-year-old friends and their two sisters who have been friends since their school days. Fate takes these characters in different directions but what unites them is the war in Karabakh. The action takes place between 1990 and 1992. It deals with war, love, and loyalty. The only social problem tackled in the film is migration. Honest and devoted soldiers, a brave and just commander, the carefree lives of rich sons in Yerevan, and all this in the background of war. There’s also (in some ways at least) a traitor: a person passing information to his Azerbaijani friend with whom he grew up in an orphanage during the Soviet times, with the sole goal of saving his life.

These honest characters seem to demonstrate that you have to serve on the front in order to become a strong man. The film was widely advertised, shown in cinemas and on public TV. Film posters were up for months across the city. Cinemas were full to the brim and shaken viewers left screenings with tears in their eyes. Nonetheless, some critics think that the film plays on patriotic and war propaganda stereotypes, which is hard to avoid while the conflict remains unresolved.

According to film critic Raffi Movsisian, the continual tension at the border and the lack of a political resolution to the Karabakh conflict has a direct influence on art.

“Directors are extraordinarily careful in this situation.

The way films are being made about the Karabakh War seems directed at a domestic rather than an outside audience. These films are targeted at young people, who all have to go through military service. They’re mostly films aimed at lifting patriotic spirit, and that’s the only way they can be made at the moment,” the film critic says.

Made in 2017 by the same director, Life and War: 25 years on tells the stories of the same characters and Armenia 25 years later. The characters, having once overcome war, collide with it again, during the Four Day War. “In Armenia as well as in Azerbaijan, the system of exalting your own nation on the back of this hatred is so strong, that calls to peace or dialogue through film have never been a priority. This kind of situation happens all over the world, in any country that finds itself in a state of conflict. That’s how it looks in Georgia or in Ukraine in relation to the conflict with Russia,” Movsisyan says

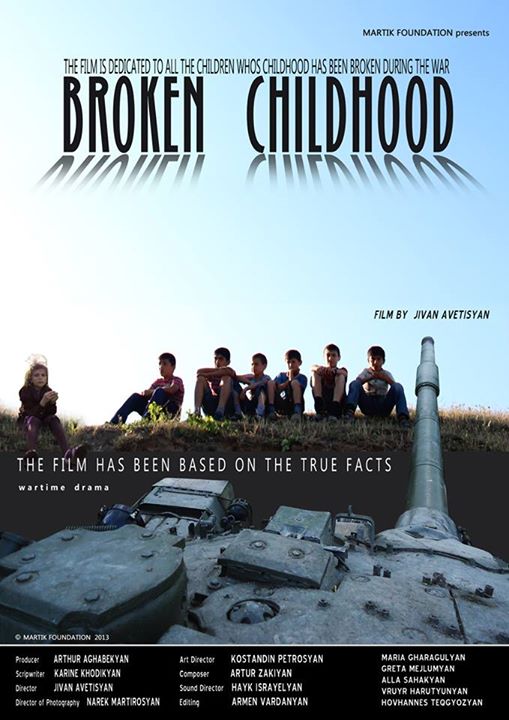

Jivan Avetisian, who is from Nagorny Karabakh himself, has dealt with the conflict in three films, Interrupted Childhood (2013), Tevanik (2014) and The Last Inhabitant (2016), all of which are distinguished by their unique take on the subject. Interrupted Childhood tells the story of the tragic events that took place in Maragha during the Karabakh War. A little Armenian girl, Lena, is taken hostage and stays with an Azerbaijani woman for 129 days before she is returned to the Armenian side. The director tries to be sensitive in his portrayal of the dramatic real events, focusing on universal human issues. Tevanik won a number of awards internationally including in China, Italy, Romania, Poland Russia, and the US among others. It was named best film in the Armenian Panorama category at the Golden Apricot International Film Festival.

The three main characters are 14-year-old teenagers Aram, Astghik and Tevanik. Although very different from each other, their story is the same: the war separates and destroys their families. Both Interrupted Childhood and Tevanik were shown at the Cannes Film Festival. Jivan Avetisian’s third film about the Karabakh conflict, The Last Inhabitant, which premiered after the April War, tells the story of 70-year old mason Abgar. As a result of the war he ends up alone in his village looking for his daughter. As it turns out, she has psychological problems after witnessing a crowd in Sumgait burning her husband alive.

In the words of the script writer of Interrupted Childhood and Tevanik, Karine Khodikian, the key message of the films is “People! Wake up and have a look what war is doing to children”.

“I hate war. People’s fates, as seen in these two films, and the colliding together of such different lives, seem only to reinforce the sentiment – I hate war. In Interrupted Childhood, the little girl is lucky she meets a woman who is also a mother. I purposefully don’t call her an Azerbaijani woman, because motherhood has no nationality. It is humanity that wins out in this film, the girl goes back to her family physically and psychologically unscathed, having somehow kept her faith in humanity. And that’s probably the biggest victory over war that was possible for the little girl and the Azeri mother,” Khodikyan says.

Apart from Jivan Avetisian’s work, film critic Raffi Movsisyan also praises Nika Shek’s 2013 film From Two Worlds as a Keepsake, which tells the story of pogroms against the Armenian population of the Azeri town of Sumgait on 27 February 1988.

“There is a scene, where the funeral processions of two young people of different nationalities meet face to face. In this film, as in the first two pictures by Jivan Avetisian, there are short scenes like these, encouraging a more sympathetic point of view, but you can’t really do much more than that in film today. We’re now in a situation where even pacificists can be called enemies, and the risk of appearing like a traitor seems to now be two, three times higher,” says Movsisyan.

Documentary films are more diverse and, thanks to a number of international projects, you can even find joint Armenian-Azerbaijani films, made with the aim of building peace. Vardan Hovhannisyan’s feature-length documentary film, A Story of People in War and Peace is an extraordinarily human story. It has been screened at many different film festivals and cinemas since its release in 2007. The film-maker has tried to understand how it’s possible to save your humanity after you’ve seen, taken part in, and survived war. A participant in the war as a journalist on the frontline, Hovhannisyan talks about fighters, bringing the years of the war and life 20 years after active combat came to an end together in one film.

The film uses rare archival footage, shot from 20-metre long trenches at the front, as well as touching stories from those who survived.

“He looks back on this period after 20 years: what happened in the lives of these people, what psychological impact the war had on them. It is a very human approach, showing that even once a war finishes it doesn’t leave them. It can follow them for their whole life, jeopardise their future and the future of a whole generation”, says Movsisyan.

This film was made with well-known international production companies such as the BBC (UK), PBS (USA), WDR (Germany), ARTE (France), YLE (Finland). It’s been translated into 15 languages and received more than twenty prominent international prizes.

Literature

The Karabakh conflict found its reflection in Armenian literature since its earliest days. According to literary critics, a human approach prevails in both poetry and prose. Some literary work on the topic of the conflict was written by people who had themselves taken part in fighting. Among these are the works of Levon Khechoyan, Ara Nazaretyan, and Hovik Vardanyan. There is a whole galaxy of other writers who did not take part in the Karabakh War, but who have written about it. These include In Expectation of the General by Hrach Beglaryan, The Truce by Hovhannes Yeranyan, and Sushi and Water by Susanna Harutyunyan.

“When we talk about the Karabakh conflict, readers usually expect stories glorifying our triumphs. There are good examples in the pathos-filled poetry of Norek Gasparyan and Robert Yesayan, essays by Vardan Devrikyan and the novel Those Who’ve Come from Hell Don’t Get Asked Questions by Martiros Vobn. There’s also a wealth of literature and many writers who don’t write about war and praise victories at all, but for whom people are the most important,” Arkmenik Nikoghosyan, literary critic, said.

Nikoghosyan notes that the majority of Armenian literature about the conflict is above all anti-war, made up of all sorts of tragic and funny episodes. In contrast with film production, Armenian literature is replete with stories preaching the importance of peacebuilding and human values.

“The main idea is that war is wrong for humanity, regardless of who commits these acts. The harm that war makes can be the strongest motivation for people to use dialogue through literature to avoid other conflicts in the future,” says Nikoghosian.

In this context, literary critics draw attention to Black Book, Heavy Beetle, the 1999 novel by Armenian writer and war veteran Levon Khechoyan.

A Literary critic Gohar Akelyan believes that Levon Khechoyan’s novel demonstrates the human tragedy in war as a whole; the process of exclusion from yourself and civilisation.

“There isn’t even any fighting in the novel, the enemy is not clearly presented, the image of the ‘Azerbaijani enemy’ is simply not there. In his writing, Khechoyan doesn’t lead his readers down the mainstream path of hate. He doesn’t make the reader feel uncomfortable with the Azerbaijani, with whom they stand face to face. Instead, he looks at the Azerbaijani from a universal human point of view. In the book, you see the perspective of a soldier who has found himself at the centre of a war and the world around him just isn’t right, it isn’t how people should live,” Akelyan says.

In Black Book, Heavy Beetle, all the colours and emotions show the gap between man and nature.

“The main idea of the book is for people to be able to step over sins they have no control over and stay guiltless, stay human,” Akelyan says.

On the level of emotion, Armenian poetry picked up the subject of the Karabakh conflict a lot earlier in contrast to prose. Since 1988, thousands of poems have been written about the war. Arkmenik Nikoghosyan specifically points out the saga ‘Flowers of Christ’ by Vardan Hakobyan from Nagorny Karabakh, and the poem ‘The summit is ours, but the lads aren’t here anymore’ by Khachik Manukyan, as works with a human-centred and humanistic approach.

The summit’s taken, but the lads aren’t here anymore The lads are on another summit They touched the stars and put them out And our stale bread was covered in sorrow So, country mine, did you win or did you lose? The summit’s taken, but the lads aren’t here anymore… (Khachik Manukyan) Tension at the border, shoot outs and incidents of breaking the ceasefire and in the conflict zone continue unabated daily, resulting in the deaths of soldiers and civilians alike. International media rarely care about this painful corner of the Caucasus, yet echoes of their pain can get through to the rest of the world through the medium of art and literature.

Poster for Life and War

Armenian novelist Levon Khechoyan