Will the trial of former leaders of Karabakh affect peace talks?

Verdict for former Karabakh leaders

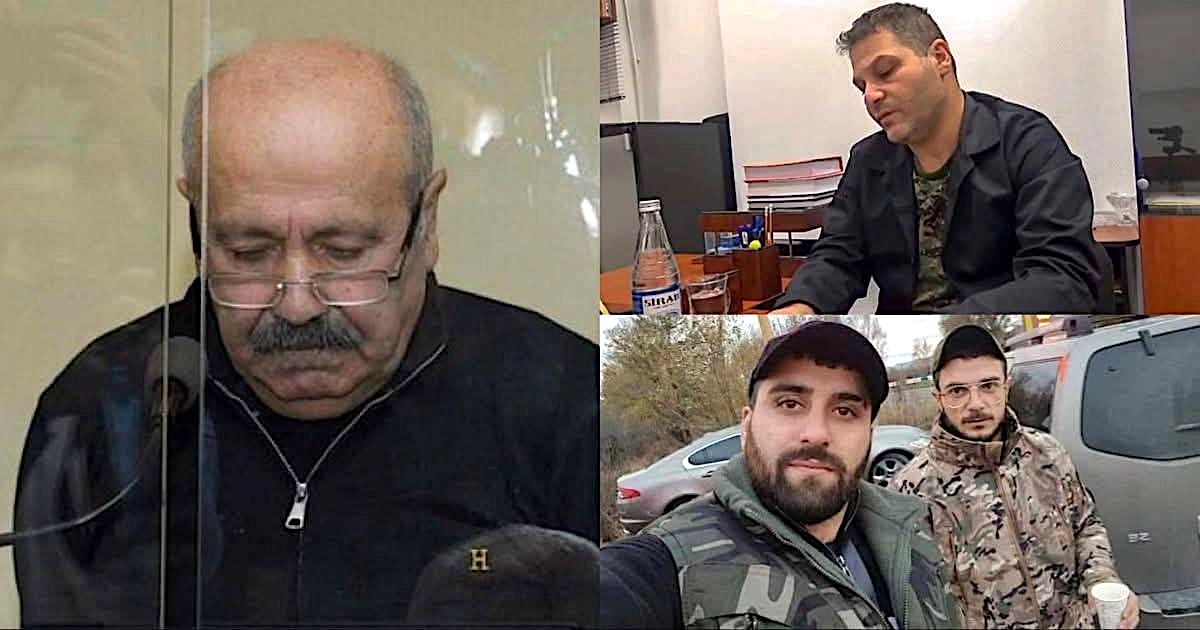

During a trial in Baku, several senior figures from the self-proclaimed Nagorno-Karabakh Republic, who had operated in the former Nagorno-Karabakh region of Azerbaijan, received harsh sentences.

Azerbaijan’s military court gave life sentences to five former leaders of the separatist administration. Prosecutors brought numerous charges against them, including war crimes, terrorism, genocide, the creation of illegal armed groups and the violent seizure of state power.

The court also sentenced two former NKR presidents to 20 years in prison.

In total, the court handed down sentences to 15 people. Azerbaijani forces detained them in September 2023 during a military operation in Karabakh. The trial began on 17 January 2025, lasted more than a year, and ended in February this year.

Verdict for former Karabakh leaders: life sentences and long prison terms

Most of those accused of serious crimes were members of the leadership of the unrecognised republic.

According to the court’s decision, the key defendants received the following sentences:

Arayik Harutyunyan — former NKR president, life imprisonment,

Levon Mnatsakanyan — former commander of the Karabakh Defence Army, life imprisonment,

David Manukyan — former deputy army commander, life imprisonment,

Davit Ishkhanyan — former parliament speaker, life imprisonment,

Davit Babayan — former foreign minister, life imprisonment,

Arkady Ghukasyan — former NKR president (1997–2007), 20 years in prison,

Bako Sahakyan — former NKR president (2007–2020), 20 years in prison.

In addition, the court sentenced eight more Armenian citizens to prison terms ranging from 15 to 19 years. Madat Babayan and Melikset Pashayan received 19 years each. Garik Martirosyan received 18 years. Levon Balayan and Davit Allahverdyan received 16 years each. Vasiliy Beglaryan, Gurgen Stepanyan and Erik Kazaryan received 15 years each.

Under Azerbaijani law, the court did not give life sentences to Ghukasyan and Sahakyan because they are over the age of 65.

The verdict states that the defendants are guilty of mass killings of civilians during the war, organising terrorist acts, creating illegal armed groups, attempting a violent seizure of state power and other especially serious crimes.

Prosecutors said the men took direct part in armed activity against Azerbaijan’s sovereignty from the 1990s. They also said the defendants made decisions that led to the deaths of thousands of Azerbaijani civilians, ethnic cleansing and torture. Among these crimes, prosecutors separately cited the killing of civilians in Khojaly, which the Azerbaijani side classifies as an act of genocide.

The case of another figure from the unrecognised entity, former state minister Ruben Vardanyan, is under separate consideration. Prosecutors have charged him under more than 40 articles, including terrorism. They are also seeking a life sentence for him.

Reactions: justice or an obstacle to peace?

These harsh sentences have triggered a mixed public reaction. In Armenia, the decisions sparked a wave of anger and were seen as incompatible with the “peace agenda.” Many Armenian politicians and human rights defenders called the trial in Baku “illegal and politicised.” They said they do not recognise the legitimacy of the verdicts.

In their view, such large-scale arrests after the war undermine the already fragile atmosphere of peace in the region. Some Armenian public figures also pointed out that the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia received the Zayed Prize for Human Fraternity in the United Arab Emirates at the same time. They described the combination of peace signals and life sentences as hypocrisy.

In response, Azerbaijani officials and experts describe the verdict as a triumph of justice. Baku says punishment for war crimes that went unpunished for decades was inevitable.

Officials note that President Ilham Aliyev had openly said for many years that those responsible for events such as the Khojaly tragedy would eventually face justice. They now say this promise has been fulfilled.

Azerbaijani analyst Elnur Enveroglu says that, in modern conflicts, states rarely bring alleged war criminals before national courts after restoring territorial integrity. In this sense, he says, Azerbaijan’s path is unique.

Local observers argue that the open trial, the presentation of evidence and the defendants’ right to defence, despite international criticism, show Azerbaijan’s legal sovereignty.

At the same time, critical reactions from some Western capitals, including France, have angered officials in Baku. International commentators close to the Azerbaijani government describe the position of countries such as France on this issue as “a blow to the peace process.”

Peace agreement and the condition of constitutional changes

In August 2025, Azerbaijan and Armenia initialled the text of a peace agreement with US mediation. However, they have not signed the document formally. Baku insists on one condition: Armenia must remove provisions from its constitution that contain claims to Karabakh.

The issue concerns the preamble of Armenia’s constitution, which refers to the 1990 Declaration of Independence. That document, citing a decision adopted during the Soviet period, states an intention to “unify Nagorno-Karabakh with the Armenian SSR.”

Azerbaijan views this wording as a legal claim by the Armenian state against its territorial integrity and demands its removal.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan has also acknowledged that the wording in the current constitution can be interpreted as a territorial claim against Azerbaijan and should change. At the same time, he says Armenia cannot amend the preamble directly from a technical standpoint. The country must instead draft a new constitution and put it to a nationwide referendum.

Work on a new constitution has already begun in Yerevan. Local officials say they could complete the draft in the first half of 2026. A referendum could then take place closer to 2027.

Analysts say a constitutional reform approved by voters could provide long-term guarantees for the peace process. Such a step would signal to Baku that Armenian society has also abandoned claims to Karabakh. Otherwise, the agreement would rely only on the political will of the current government, which would leave it vulnerable to domestic political changes in Armenia.

For now, both sides expect to sign the peace agreement only after constitutional changes. Once they sign the document, the two countries will formally recognise each other’s territorial integrity. They will also implement provisions on diplomatic relations, the opening of borders and the restoration of communications.

This could mark the start of a new phase in the South Caucasus and open a period of long-term peace and cooperation.

At the same time, the process remains fragile, and further steps to build mutual trust remain crucial.

Could the detainees become part of a political bargain?

As the peace process moves forward, one of the most discussed humanitarian issues remains the fate of Armenians in detention in Azerbaijan. Official Baku considers these individuals war criminals and treats them accordingly, rather than as ordinary prisoners of war. At the same time, the past two years have seen several prisoner exchanges and unilateral humanitarian steps.

At the end of 2023, agreements between Azerbaijan and Armenia led to the release of more than 30 Armenian servicemen, who returned to Yerevan. In exchange, Armenia returned the last two Azerbaijani prisoners to Baku. At the end of 2024 and the beginning of 2025, mediators including Russia, Western countries and the International Committee of the Red Cross helped secure the release of small groups of Armenian detainees.

One of the most significant steps came on 14 January this year. On that day, Azerbaijan released four Armenian detainees, while Armenia handed over two men who had spent years in prison. They were Syrian mercenaries captured during the 2020 war.

Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan confirmed the exchange on his Telegram channel. He said the four freed Armenians were in satisfactory condition and were already on their way to Yerevan.

Courts had earlier sentenced the released Armenian detainees to prison terms of between 15 and 20 years. Prosecutors had charged them with crimes including genocide, espionage and illegal weapons possession. Both Baku and Yerevan presented the exchange as a sign of improving bilateral relations.

Could the fate of the former senior Karabakh leaders sentenced to life imprisonment change?

Azerbaijani officials do not publicly raise the issue of a possible “pardon” or “exchange” for these men. Instead, they stress that those convicted must fully answer for their actions, and they present the verdicts as a matter of upholding the rule of law.

A significant part of Azerbaijani society also supports this position. Many in the country call for remembrance of the Khojaly tragedy and other crimes. In such circumstances, releasing these prisoners without regard for domestic opinion would be politically risky for Baku.

At the same time, international mediators and human rights groups continue to focus on the detainees’ future. Ahead of the planned visit by the US vice-president to the region, dozens of international rights organisations appealed to him to help secure the release of Armenians held in Baku.

In Armenia, many also hope that after the signing of a peace agreement and the adoption of confidence-building measures, Azerbaijan may make a humanitarian gesture and return some of the prisoners.

Lawyers for the convicted men say that, although the sentences are final from a legal standpoint, a political review remains possible. They mention options such as a pardon, extradition or transfer to a third country, which could become subjects of negotiations.

Ultimately, the further course of the Armenian-Azerbaijani peace process will largely determine how this complex issue develops. If Armenia carries out constitutional changes and both sides fully sign a peace treaty, observers expect the region to turn a page on years of hostility.

In such a scenario, both sides may make certain concessions to address the humanitarian consequences of the long conflict. Some observers do not rule out that, in order to strengthen peace, Azerbaijan could hand over some prisoners to Armenia or reduce their sentences.

However, such decisions would be difficult. Leaders in both countries would have to balance domestic public opinion with international pressure.

Verdict for former Karabakh leaders