Kazakhstan’s Anti-LGBT 'Jihad'

Anti-LGBT law

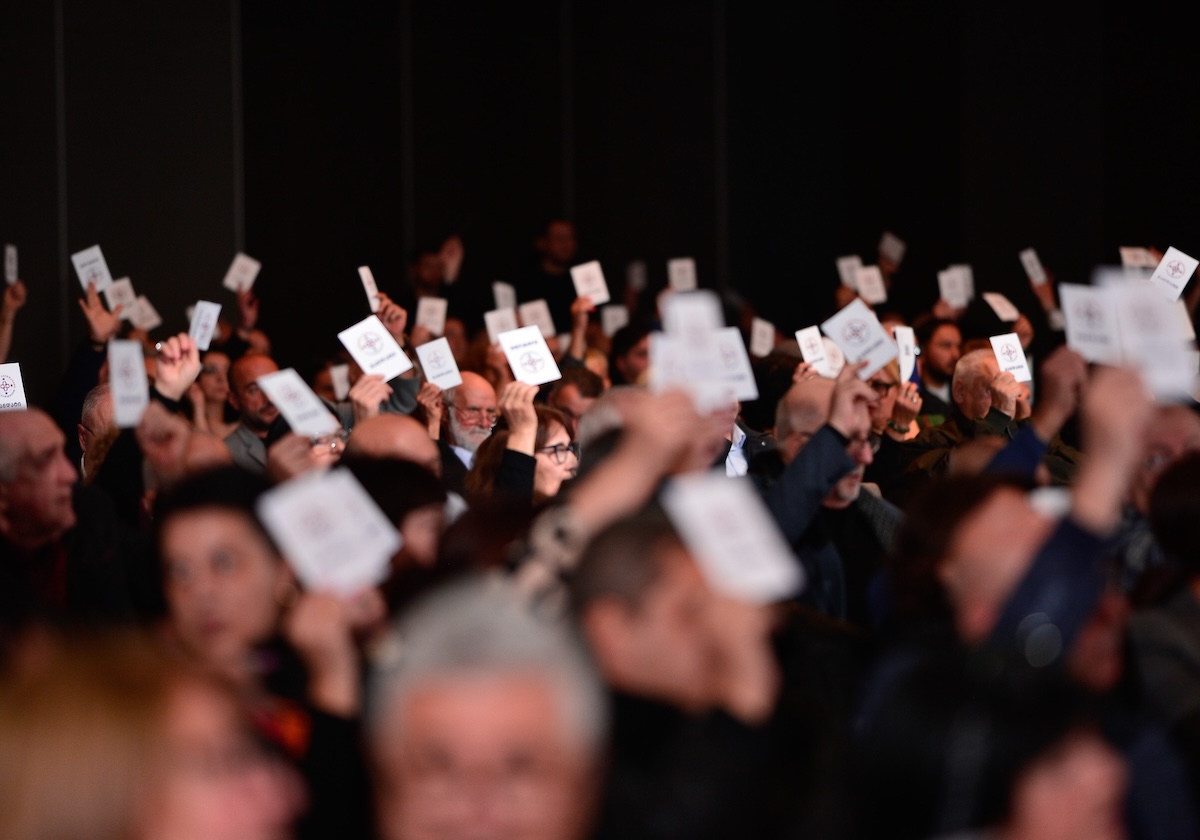

Kazakhstan is effectively becoming a new member of the “club” of countries with anti-LGBT legislation. The Mazhilis, the lower house of parliament, has unanimously approved amendments introducing a ban on so-called “LGBT propaganda”. Placed alongside it — through a manipulative use of the conjunction “and” — is the promotion of paedophilia, which is already a criminal offence in almost every country in the world.

Our colleagues at Factcheck.kz explain why the law banning “LGBT propaganda” is dangerous.

The amendments affect nine laws and introduce fines, with repeat violations punishable by up to 10 days of administrative arrest. The next step lies with the Senate and President Kassym-Jomart Tokayev, who are expected to approve the changes in one form or another.

Post “If You Have No Wings, At Least Let Me Fly.” The Case of Kesarija Abramidze’s Murder

The authorities are clearly following a trend fashionable among authoritarian regimes, framed as the “defence of traditional values”. In recent months, Tokayev has repeatedly referred to this rhetoric in public — including in a notably deferential message to Donald Trump, whom he described as a “great leader sent from above to restore common sense and traditions”. He delivered a similar message to a Russian audience:

“We are united by a shared understanding of traditional values.”

Why Is Kazakhstan Joining the ‘Anti-LGBT Club’?

For authoritarian regimes, there are few arguments against democracy. Quality of life, personal freedoms, and opportunities for self-realisation are all higher in democratic countries. Talented people move there, officials buy property there, and children are sent there to study.

However, propaganda—primarily Russian—has managed to distort this picture: in the popular imagination, democracy has come to be associated not with free and fair elections, but with “gay parades and LGBT propaganda.” This argument has proven to be universal and especially effective in post-Soviet societies—an eclectic mix of religiosity, conservatism, Soviet nostalgia, and an identity crisis.

Post: “The Party of Global War,” “the Deep State,” and Other Conspiracy Theories in a Statement by Georgian Dream

Under the slogan of “protecting children,” it is possible to justify election fraud, censorship, and repression. Anti-LGBT campaigns allow the majority to be mobilised against the liberal-minded segments of society—young people and urban opposition thinkers. LGBT people become a convenient and safe enemy onto whom societal anger, frustrated with the economy and politics, can be directed.

In addition, such laws create the illusion of vigorous activity and reform. Public debates about “morality,” censorship of films, books, posts, and even appearances compensate for the lack of real political and economic change and distract from systemic problems.

Anti-LGBT Geography

There are around 60 countries in today’s “anti-LGBT club.” In the most radical group—Iran, Saudi Arabia, Qatar, Brunei, Uganda, and others—same-sex relationships are criminalised, with punishments that can include the death penalty. Separately, there is the post-Soviet bloc (Russia, Hungary, Bulgaria, Georgia, Kyrgyzstan), where “propaganda” is banned, but the relationships themselves are not criminalised.

Kazakhstan now finds itself in this group. It is important to note, however, that the country had previously left this “club.” In 1997, the Soviet-era law on “sodomy” was repealed, and in 2009, transgender transition was legally permitted.

‘Traditional Values’: What Does That Even Mean?

The bill has drawn sharp criticism from experts and human rights defenders, who point to its similarity to Russian laws. Mazhilis deputy Zhanarbek Ashimzhanov denies this, claiming that Kazakhstan is acting independently and taking national specifics into account.

However, invited researcher Erkebulan Sairambayev argues that it is essentially a copy of the Russian model, which “undermines decolonisation and separation from Russia.”

Political scientist Dimash Alzhanov describes it as following the Kremlin narrative of mobilising society through the image of an external threat. Human rights activist Yevgeny Zhovtis calls what is happening “pure political technology.”

The key problem is the lack of a clear definition of “traditional values.” It is a flexible and subjective concept that allows for selective law enforcement. By default, it refers to heterosexual relationships, the patriarchal family, prioritisation of childbearing, and a conservative way of life. In an authoritarian context, it also serves as an alternative to universal human rights.

Does ‘Propaganda’ work?

Medical and scientific experts emphasise that “LGBT propaganda” does not exist. Psychiatrist Anar Karazhanova explains that sexual orientation is not the result of a conscious choice and cannot be shaped or changed by external information:

“This is connected to hormonal and deep unconscious processes.”

Factcheck.kz has previously noted that propaganda involves systematic, manipulative influence on public opinion. LGBT content does not meet these criteria and is simply a representation of a social group.

‘Protecting Children’: facts vs. myths

A comparison of international statistics shows that “traditional values” do not guarantee family well‑being. In the Netherlands, Sweden, and Denmark, birth rates are higher and divorce rates lower than in Russia and even Kazakhstan.

UNICEF data for 2025 show that children in countries without bans on LGBT content have better mental and physical health outcomes. Denmark, where so‑called “LGBT propaganda” supposedly thrives, consistently ranks among the happiest countries in the world.

How will this work in practice?

Enforcement mechanisms remain vague. The law mentions an 18+ rating and a ban on “positive evaluation,” but it is unclear who will determine what counts as “positive” or “negative.” Lawyers warn that the use of “community assistants” could lead to arbitrary denunciations and a climate of “witch hunts.”

In theory, the ban could cover everything—from books, films, and theatre productions to rainbow-coloured clothing or toys. Questions also arise about the fate of global platforms like YouTube, Instagram, and X, which are not subject to Kazakhstan’s jurisdiction.

In practice, only negative references to LGBT people would become legal—effectively institutionalising hate speech.

Possible consequences

Experts warn of censorship and self-censorship, a reduction in freedom of speech, the removal of classic literature and films, the stigmatization of LGBT people, economic losses, and decreased investment. Publishers note that works by key figures of world culture, including Ginsberg, Foucault, Proust, Wilde, and others, could come under attack.

According to the Badgett model, discrimination against LGBT people costs countries 0.1–1.7% of GDP per year. For Kazakhstan, this amounts to up to $900 million annually. The UN has already stated that the law is based on misinformation and gives legal force to prejudice.

Why now?

Experts link the initiative to changes in the global context—primarily the return of Donald Trump and a weakening of international pressure. Yevgeny Zhovtis notes that previously the authorities were reluctant to damage relations with the US, but now “they can—and nothing will happen for it.”

Galym Zhusipbek adds that homophobia is a product of the Soviet legacy and criminal subculture, which society needs to overcome rather than enshrine as state policy.

‘International experience,’: selectively сhosen

The authorities cite Hungary, Bulgaria, Kyrgyzstan, and Poland, while ignoring inconvenient facts. In Poland, “LGBT-free zones” were declared discriminatory and annulled. In Lithuania, a similar ban was overturned by the Constitutional Court. These measures have not proven effective and have faced criticism from European bodies and UN mechanisms.

Nevertheless, Kazakhstan, like other authoritarian regimes, selectively chooses examples that fit the ideology it seeks to promote.

Anti-LGBT law

Supported by Mediaset