Obstacles to studying Soviet history: who's hindering research in Georgia and why?

KGB archive in Georgia

Access to archives containing information about the Soviet period of the Georgia’s history is becoming increasingly difficult, say local researchers. They believe that the Georgian government deliberately complicates the process of researching the Soviet past. As a result, there is a deficit of scientific research on this topic, while Russian disinformation is freely disseminated.

The “Soviet Past Research Laboratory (SovLab) is one of the leading research organizations of its kind in Georgia.

Recently, with its support, the book “Georgia Against Stalin” by Lasha Bugadze was published. The book covers the period from 1900 to 1922 and is dedicated to Joseph Stalin’s involvement in the annexation of the Georgian Democratic Republic. Bugadze portrays Stalin as an adversary of democratic Georgia, a figure who “stole” the 20th century from Georgians.

Bugadze believes that Georgian society is still captive to myths about Stalin. As an example, the writer mentions a recent incident where Stalin was depicted on an icon at Sameba, the main cathedral in Tbilisi, and some in society did not see any problem with it.

“Praying to Stalin is an oxymoron. How can one consider a person who killed 35 million as a believer?! All of this stems from ignorance. People don’t know the past. As a result, Russian Soviet myths easily gain credibility,” says Bugadze.

He is convinced that attempts to revive the cult of Stalin are also part of the hybrid warfare unleashed by Russia.

Dangerous trend

Researchers delving into Georgia’s Soviet history argue that the nation has become a focal point of Russian hybrid warfare: Russia endeavors to disseminate myths about a common past to uphold its influence in Georgia.

Experts argue that this is an obvious threat, yet nothing is being done to neutralize it. Instead of fostering research into the Soviet past within the country and disclosing more scholarly information about totalitarianism, the ruling Georgian Dream party, on the contrary, creates obstacles for researchers.

“This is not a recent trend, but one that spans decades,” asserts historian Irakli Khvadagiani. “The system further tightened its grip post-2012 [coinciding with the rise to power of the Georgian Dream party]. While obstacles and legal discrepancies existed before, the situation has escalated and appears to be strategically orchestrated.”

- Hiding directories and complicating document access.

- Abuse of personal data protection laws.

- Imposing high prices for archival materials.

- Maintaining closed archives under the ministry of internal affairs.

Sovlab researchers enumerated these and other formal and informal restrictions.

Giorgi Kandelaki, the head of the Sovlab project, cites the investigation into the location of mass graves of victims of the totalitarian regime as an example. There are many such graves, he says, but only one has been uncovered so far. “Finding the exact locations is difficult due to researchers being denied access to maps,” says Giorgi Kandelaki.

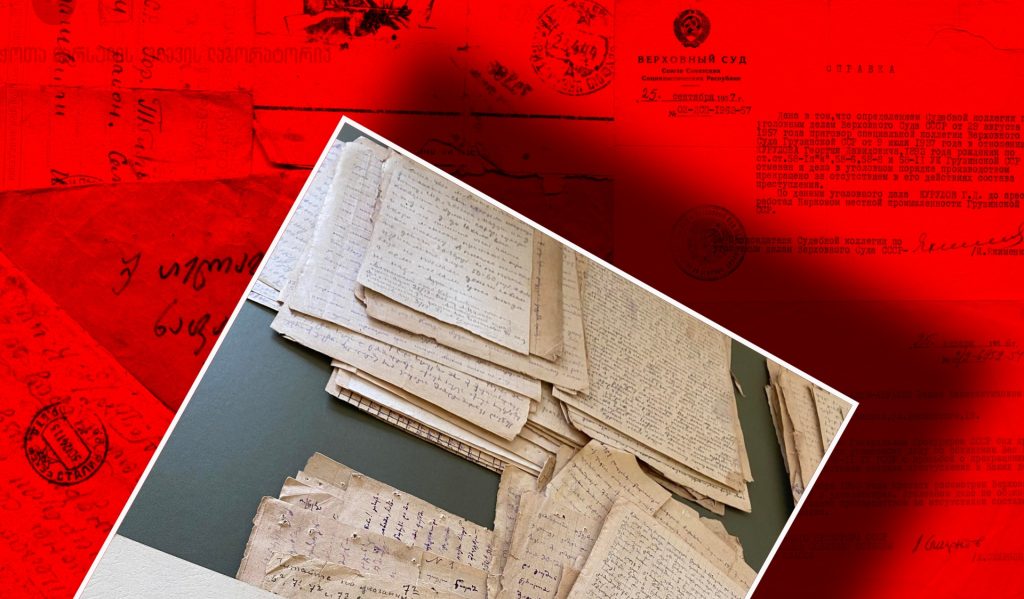

Classified archive

The archive of the academy of the ministry of internal affairs stands as one of the crucial repositories housing documents from the Soviet era. It holds documents from the Communist Party and the USSR’s state security committee (KGB), serving as the main workspace for researchers studying the Soviet past and totalitarianism.

The Georgian ministry of internal affairs archive’s official page states that it’s open to everyone, including researchers, journalists, and history enthusiasts.

However, for months, both the public and researchers have faced limited access to the unique materials stored here. The archive is completely closed, purportedly due to reorganization.

However, historians doubt this explanation.

“If there’s truly a reorganization, why keep the public in the dark? What’s with all the secrecy? And why completely shut down the archive’s operations? With the current pattern, we might see this situation drag on indefinitely. Even if the archive reopens officially, things could worsen,” comments Irakli Khvadagiani.

“In truth, there’s no actual reorganization happening here; this restriction is purely political, reminiscent of practices in Russia,” historian Badri Okudzhava states.

JAMnews reached out to the ministry of internal affairs press service seeking clarification on the closure of the archive. They recommended submitting a written request. However, despite the legally mandated 13-day period passing, no response has been received regarding the closure of the archive or its future availability.

Badri Okudzhava reveals that he and his colleagues have been unable to progress on specific projects related to studying the Soviet past for several months:

“We’re currently collaborating with Ilia State University, supported by the US embassy, on a project to document the Soviet-era history of six cities in Georgia. However, these restrictions are directly impeding our progress. We’re unable to access vital information about the cities, including details about anti-Soviet uprisings.”

Nodar Chkhaidze, a doctoral student at Tbilisi State University’s faculty of history, shares a similar frustration:

“I’m currently working on a specific research topic, but progress has stalled due to the complete closure of the KGB archive. If this situation persists, our research could be delayed for years.”

“The history of the 19th and 20th centuries must be fundamentally rewritten. Without access to documentation, how can researchers accurately document events? Otherwise, people will be left with nothing but mythology tainted by propaganda,” Chkhaidze asserts.

Рigh tariffs for services at the National Archives

Another significant obstacle for researchers is the high tariffs for services at the National Archives. For instance, photocopying and certifying a document from the 19th century costs 3 lari [approximately $1] per page, and obtaining a copy can take up to 24 hours after submitting the request.

Sometimes, two or three thousand copies of pages are needed for just one study.

“Considering that researchers typically earn fees ranging from 1,200 to 1,500 lari [approximately $453-565] in such projects, these prices are absurd. It’s entirely unclear why we’re paying for our own history, why these materials aren’t open and free for everyone,” says Badri Okudzhava.

Restrictions on personal data

Another challenge researchers have grappled with is the restriction on accessing personal data.

“Supposedly, for the sake of personal data protection, we’re barred from accessing any documents less than 70 years old. If we request such documents, all personal data within them will be redacted,” states Giorgi Kandelaki.

This limitation, he explains, complicates the study of pivotal events like the protest rallies on April 14, 1978, and April 9, 1989.

Since 2017, Sovlab has been embroiled in a legal dispute with the National Archives after Irakli Khvadagiani requested data on citizens who were massively deported by the Soviet regime and survived the GULAG. He was denied access to the information.

Researchers identify a problem stemming from the fact that archival policy in the country is overseen not by the ministry of tducation, but by law enforcement agencies. Giorgi Kandelaki believes that the State Security Service unofficially oversees various archives, dictating who is granted access and who is denied.

Despite the expectation that the State Security Service of independent Georgia would be interested in publicizing the crimes of the Soviet totalitarian regime extensively, Kandelaki notes that in practice, the opposite occurs:

They see themselves as the heirs of the Soviet Union and are fundamentally opposed to this information becoming public knowledge.

JAMnews reached out to the National Archive for comments on the matter. Specifically, we inquired about the procedures for accessing archival information. In their written response, the archive administration stated that they operate in accordance with the law, including procedures for granting access to individuals interested in archival documents and/or their copies.

What is the purpose of these restrictions?

“Why the KGB archive is classified, why are they doing this? As a result, the level of political education about the past, Russian imperialism, and totalitarianism remains low,” says Khvadagiani.

“Meanwhile, continuous Russian propaganda is underway, the far-reaching plan of which is either to completely forget these crimes or to transform and tailor them to the goals of Russian information warfare,” he says.

“Long-term goal – to disorient society in Georgia, ignite anti-Western sentiments, and increase pro-Russian sympathies. Ignorance of the past and lack of information about Russian imperialism and totalitarian history precisely contribute to this,” says Khvadagiani.

Georgian researchers believe that local restriction practices are very similar to those in Russia and suspect that these actions are coordinated with Russian institutions.

“When archives are open, transparent, and accessible, the true face of Russian occupation and totalitarianism is clear and unadulterated. This does not suit our government, as it is pro-Russian, engaged in information manipulation, anti-Western rhetoric, and the promotion of pro-Russian sentiments. Accordingly, if citizens receive true information, this will pose a serious challenge to the authorities,” believes Irakli Khvadagiani.

“These restrictions are so artificial that they raise suspicions that they are created deliberately. And, of course, these restrictions come from the top,” says Nodar Chkhaidze.

Writer Lasha Bugadze also believes that the current government intentionally blocks the study of history and criticism of certain cults, including, for example, the cult of Stalin:

“This is happening in Russia, and we may be dealing with the same trend.”

The writer argues that the interest in rewriting or hiding the Soviet past is not new. And the fact that it is gaining momentum now in Georgia is a continuation of the processes initiated by Vladimir Putin in Russia long ago. And the reason is simple – gaining control mechanisms.

“Dictators and tyrants always fear memory, historians, writers, journalists,” says Lasha Bugadze.

Why is the KGB archive classified in Georgia?