Locals trying to save the village of Griz and their native language from extinction

Griz and their tongue on the brink of extinction

This is the village of Griz, ne of the most remote villages in Azerbaijan. It is located at an altitude of 2,200 meters above sea level in the Greater Caucasus Mountains.

Griz live here – an ethnic group that shares the name of the village. According to some sources, the population of Griz at the beginning of the 19th century was about eight thousand people. According to the results of the 2009 census, only 274 people now live in the village. But in fact, there are far fewer than that.

Local residents say that the poor condition of the village’s roads hinders the creation of other infrastructure and reduces the standard of living, so young people leave Griz, and this puts the ethnic group and its language on the brink of extinction.

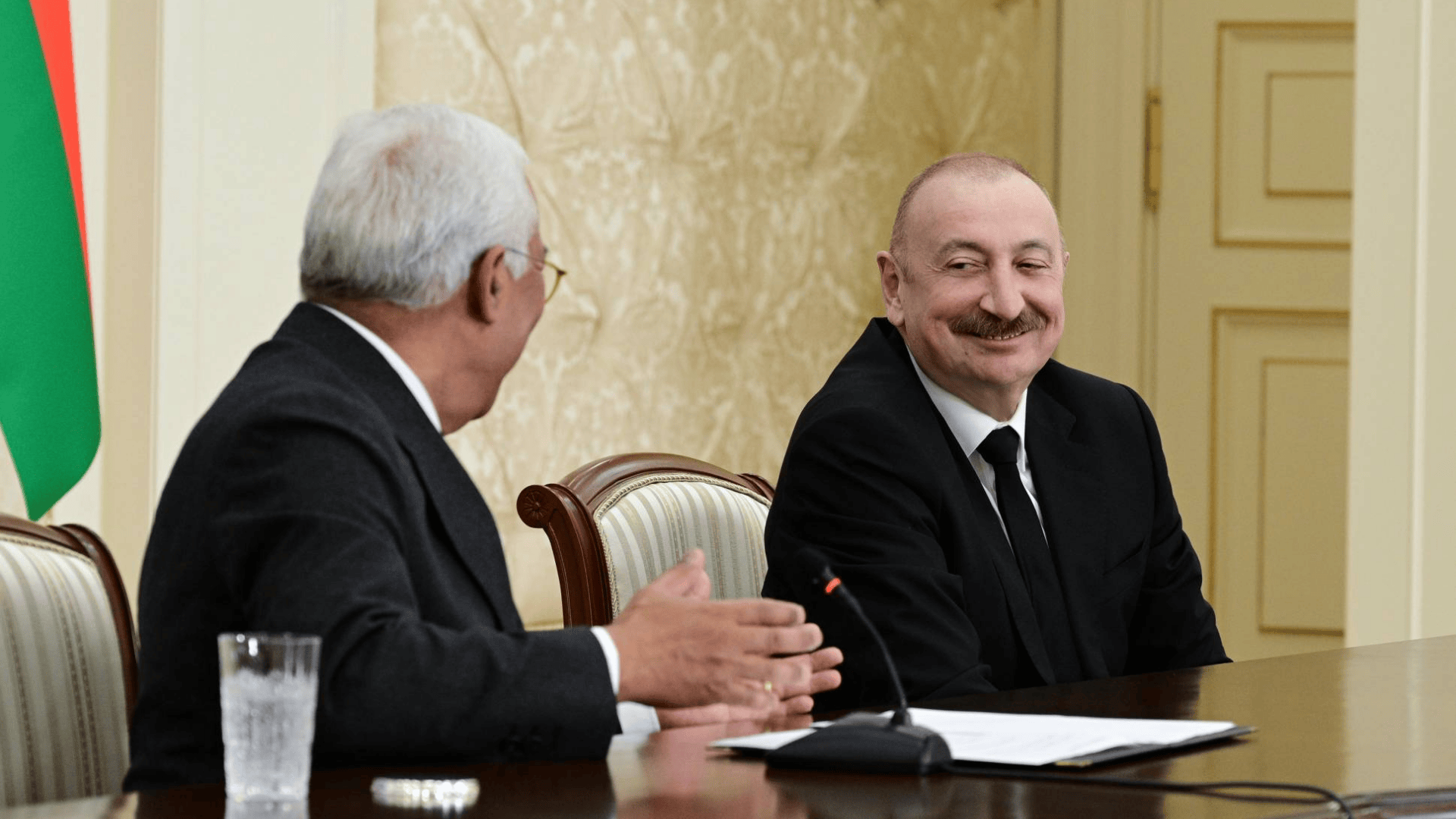

“Alpine allowance” for civil servants

Farhad meets us in the center of Guba. We transfer from our car to his Niva, and in a few minutes a real off-road adventure begins.

Without stopping, we climb a dirt road for about 40-45 kilometers. Sometimes the road passes through such narrow paths over steep cliffs that the four wheels of the car can hardly fit onto the narrow track. These roads are not for “urban drivers”. If your path lies in Griz, then you should definitely find a local driver.

I begin to feel an increase in blood pressure, deafness and headache with the increase in altitude. Farhad says that for people unaccustomed to mountain life, this is normal.

Civil servants (teachers, medical staff, librarians) and pensioners in Griz receive a monthly salary and pension supplement of 30 manats [about $18] just for living in the highlands. The rest of the “alpine allowance” is not paid.

“The highlands only affect those who receive a salary from the state,” Farhad jokes and smiles.

“Once we had to dig the same grave for three days”

Finally, we get to Griz, but Farhad had to tell me this. I’m not used to seeing such a village. There are only steep rocks around, old tombstones that have sunk into the ground. No people, trees or plants around; there is nothing for the latter to grow on.

According to local residents, graves are dug where it is still possible to dig somehow. Digging a grave in Griz is the hard work that all the men of the village do for many hours. It is said that once they had to dig a grave for three days.

The village is empty

As already indicated, the difficult geographical position and the lack of a normal road completely isolate the village from the outside world in winter.

Since ancient times, the majority of the rural population here has been engaged in animal husbandry, leading a nomadic life — people moved to villages in winter and returned in summer. In the winter months it is impossible to feed livestock in the highlands, severe weather conditions lead to diseases and death of animals. So livestock breeders bring their herds to the villages located in the lowlands.

But over time, the Griz began to settle in the villages in the Guba and Khachmaz regions. As a result about 30 villages and settlements were formed, where representatives of this ethnic group live. Thus over the past century and a half, the population of Griz has decreased from 8,000 to 274 people (2009 data).

And today, apart from the local civil servants, who can be counted on two hands, the majority of the village population leads a nomadic lifestyle. We found ourselves in Griz at the very beginning of spring, in the last days of March, but there was still snow on the side of the road. There were almost no people in the village. They have not yet returned from the village.

“People are leaving Griz. There is little left. They leave for various reasons, mainly because of financial problems. They are not to blame, everyone has to get by somehow. No one will leave their native place if they live well,” Shikhbaba Mehdiyev, a 71-year-old resident of Griz, says.

Language in danger of extinction

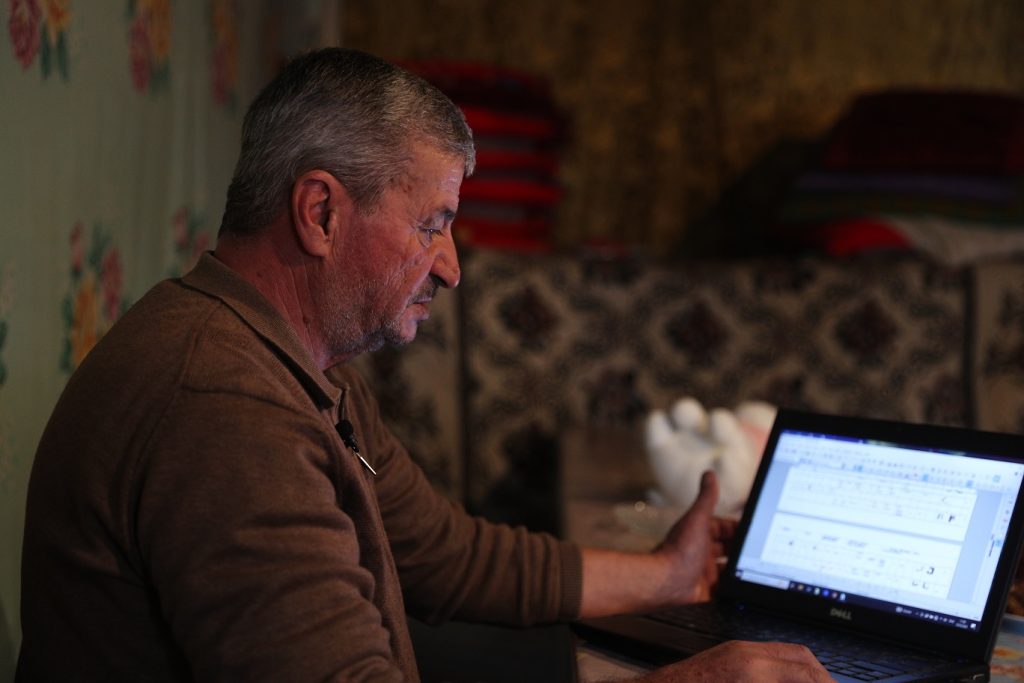

Shikhbaba Mehdiyev was born and raised in Griz. For many years he taught mathematics at a nine-year incomplete secondary school in the village, and was the principal from time to time. Now he is retired.

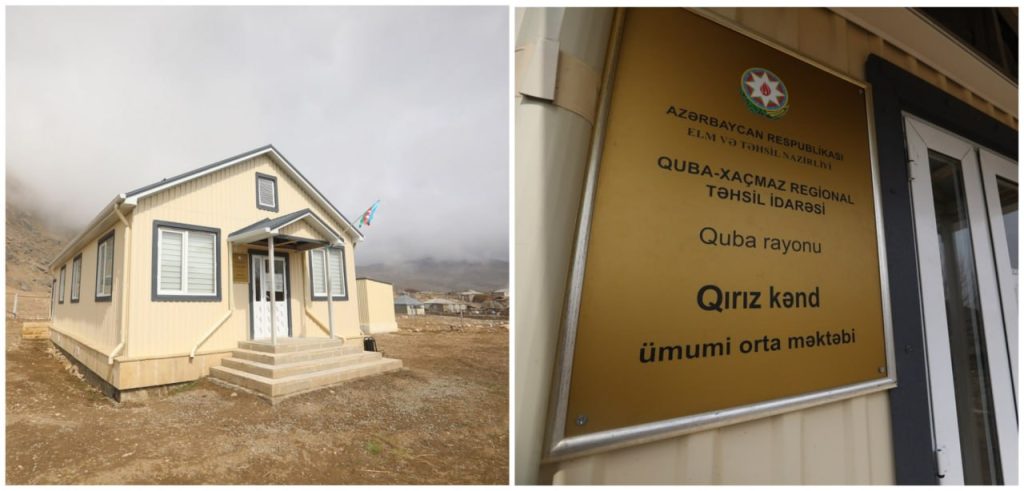

According to Shikhbab muallim (the word “muallim” is translated from Azerbaijani as “teacher” – JAMnews), three years ago, when he taught in the old building of the village school, about 70 children studied there. Two years ago a new modular school appeared, but now there are no more than twenty students.

With the outflow of young people from the village, and a decrease in the families of children who speak the Griz language, Shikhbaba muallim fears that their native language may completely die out.

Griz are considered one of the most ancient peoples of Caucasian Albania. The Griz language, along with Lezgi, Rutul, Budug, Khinalyg, Tsakhur, is included in the group of languages of the Shahdag peoples of the Iber-Caucasian language family. Despite the common origins, these languages differ from each other.

Until today, the Griz language has been passed down orally from generation to generation. A decline in the number of those who speak this language threatens its extinction in the near future. Worried about this, Griz intellectuals have discussed the need to publish books in their native language. One of these intellectuals is Shikhbaba Mehdiyev.

On the day we arrived in Griz, the first illustrated dictionary of the Griz language, prepared by Mehdiyev, was published, and the first copies of the book were brought to Guba. And so we saw the book before its author. Moreover, on the way to Griz, Farhad gave us two copies.

Currently, Shikhbaba muallim is working on a dictionary with voice acting. This dictionary will include about two thousand words.

“The first dictionary of the Griz language was compiled by Shamsaddin Sadiev in the 1950s. He also published a book on the grammar of the Griz language. And three years ago, a wonderful dictionary compiled by Israfil Hummatov was published. He is my classmate. Originally from Griz, but now lives in Khachmaz. We compiled a dictionary together with the German scientist Monika Rind-Pavlovsky,” Shikhbaba says, adding that it is not enough to publish dictionaries of the Griz language, more textbooks are needed. But this should be done by specialists.

“How to teach a language if there is no scientific literature?”

Despite the fact that the languages of some ethnic minorities are taught in schools, this has never happened with the Griz language, though in Soviet times there was a proposal to introduce the teaching of the Griz language once a week into the curriculum, as well as other minor languages. But the elders of the village and the intelligentsia, after conferring, refused to do so.

“We were offered to replace one of the two academic hours allocated for Azerbaijani language lessons with Griz language lessons. But the elders of the village, and I, too, came to the conclusion that the study of the Azerbaijani language is more important for us. In those years, schoolchildren from Griz spoke their native language all day long. And when they went to school, practically none of them knew a word of Azerbaijani. And in society, knowledge of the state language is necessary. To continue education, enter the university, get a job for our children, it was obligatory to study the Azerbaijani language. Of course, we would not refuse if we offered an additional lesson in the Griz language, as, for example, is customary with Lezgin, and not instead of one of the two lessons of Azerbaijani. But the conditions were set like this,” Shikhbaba muallim says.

According to him, another problem of teaching Grizian in schools is the lack of scientific literature in this language:

“At that time we had only one dictionary in our hands, compiled by Shamseddin Sadiyev, and it did not cover a large number of words. Without scientific literature, textbooks, even if the teacher himself is not very knowledgeable about the subject, does not know the rules of the grammar of the language, how to teach it? Unlike us, in Khinalig the same year they began to study their native language. And what have they been teaching there all these years, what literature do they use, what textbooks do they use? I won’t worry about it, because there is nothing like that.”

In mid-March 2023 the Cabinet of Ministers of Azerbaijan reported that work was underway to publish sets of textbooks for the first grade of primary school in the Khaput language, and textbooks for grades I-IV in the Talish, Tsakhur and Khynalig languages. In other words, from the next academic year, the languages of some ethnic groups will finally be taught using textbooks. But there is still no Griz language among them.

The first signs of Islam in the territory of modern Azerbaijan

Griz is unique not only for its nature, but also for its ancient history. But due to the fact that the village is located in a remote and inaccessible area, these features do not bring any benefit to the local population. On the territory of the village, historical monuments and graves are not studied, they literally disappear because no one takes care of them.

For example, this is the Abu Muslim mosque. It was built in 131 Hijri (VIII century) by Abu Muslim himself.

“Abu Muslim was the brother of the Arab Caliph and commander. In 128 Hijri (the chronology in Hijri starts from 622, but the Muslim year lasts 355 days, so it is not easy to transfer the Hijri years to the modern way), after the conquest of Derbent, Aran was Islamized. And then he moved to the territory of then Caucasian Albania and built this mosque. There are mosques of the same name and almost copies of this one in the villages of Khinalyg and Dzhek. The mosque in Khinalyg is better preserved. And the mosque in Dzhek was repaired by the local population 30-35 years ago, also in good condition. In Griz, almost everything is destroyed,” said Shikhbaba muallim.

According to him, the first signs of Islam in Azerbaijan are located exactly where Caucasian Albania was located.

The only bek from Griz

Griz witnessed the bloody tragedies committed in 1918 by the Bolshevik army, consisting mainly of Armenians, in and around Guba.

“At that time the population of the village, led by Suleyman bey, met the army of Anvar Pasha, the commander of the Turkish army, who came to support the Muslim population from the Bolsheviks, here on the main square. Sacrifices were made for them, dinner was prepared, the table was laid right on the square. The son of Suleiman Bek died in these battles.”

Shikhbaba showed us the grave of Suleyman bey and his son. According to him, Suleyman bey is the only bek who comes from Griz.

“The Griz never had a system of domination of the beks. There was only a communal system of government. He is the only one who was the general of the king, received the Order of St. George. Therefore he was given the title of bek, and they gave him four hectares of land in the lower part of the village,” Shikhbaba Mehdiyev says.

“The builders of the new road left for Lachin”

Shikhbaba Mehdiyev considers it painful that a village with such a unique nature and history is turning into an abandoned place. In his opinion, if there is a new road here the village will come to life, it may even become better than it ever was. And then the Griz will return to their native places.

In fact, construction of a road that will join the Guba-Khinalyg road has already begun:

“They are building a good road with a width of 12 meters, the asphalt surface will be eight meters wide, two-lane. Work went well, but then stopped. Didn’t work last year. They say that the company went to Lachin to build an alternative road there. Last year they arrived, worked for 10-15 days and left. No work was carried out in autumn and winter. I think they will return in the spring and continue their work…”, Shikhbaba hopes.

“The construction of such a road probably says something. It is very convenient for the development of mountain tourism, for this we have good sites at the top, suitable for winter tourism. If they create something like that, people will return to the village. There will be jobs for people, and the village will return to its former life.”

With the support of “Mediaset”