Op-ed: Georgia-NATO, 10 years of walking in circles

Heritage Foundation researcher and international policy commentator Luke Coffey published an article at the beginning of February in which he wrote about an alternative way for Georgia to potentially receive NATO membership.

He wrote that Georgia’s joining the North Atlantic Treaty Organisation can be expedited, albeit under one condition: if the fifth article of the NATO agreement on collective defence temporarily excluded Abkhazia and South Ossetia.

Critics say that agreeing to such a condition will effectively be seen as Georgia renouncing Abkhazia and South Ossetia. Supporters of Luke Coffey’s idea see other issues as well.

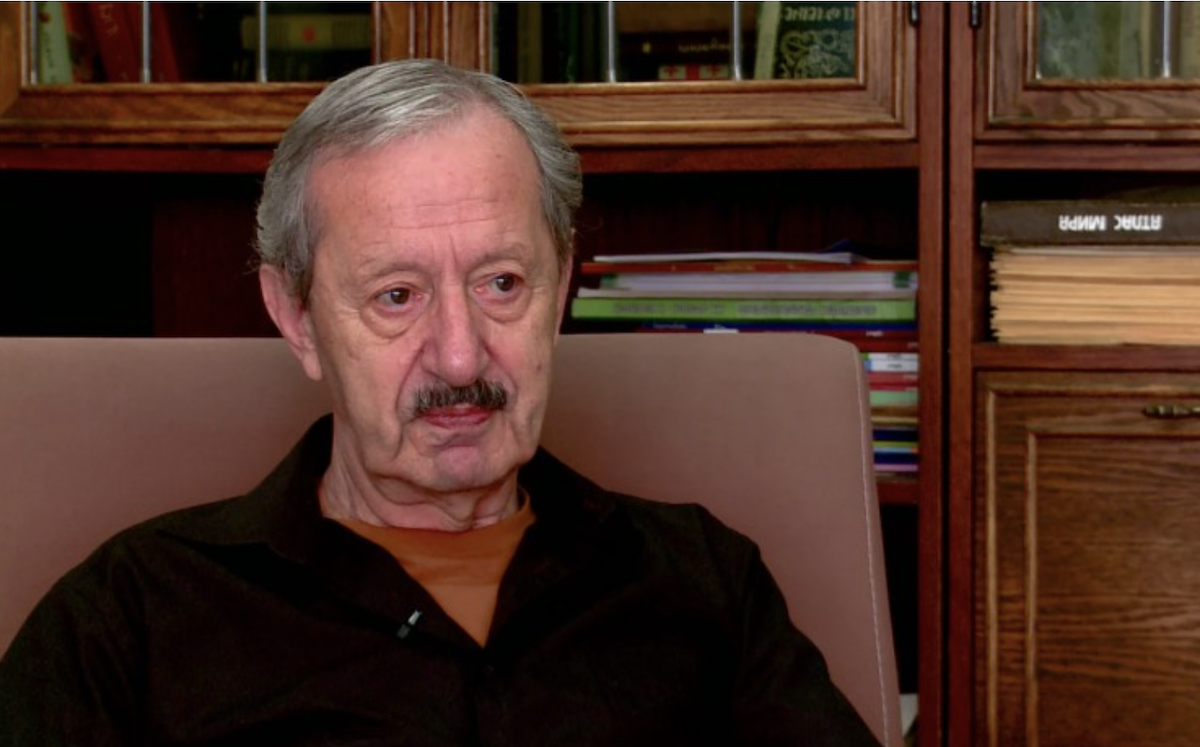

At the request of JAMnews, the head of the international relations programme at the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs Tornike Sharashenidze explains the idea in depth and looks at the likelihood of it becoming a subject of serious discussion.

After Luke Coffey wrote his controversial article, the discussion on Georgia’s integration with NATO took on renewed fervour. Coffey offered to solve the problem of integration in the following way: Georgia enters NATO, but the 5th article will not apply to the occupied regions until they fully return into the folds of Georgia.

[Article 5 of the NATO agreement states that members of the alliance must defend and ward off an attack on any other member state. An attack on one state is viewed as an attack on the entire alliance.]This idea is not entirely new and has been discussed for a while now. However, if one is to judge the reaction of the Georgian public, it would seem that this is the first time that Georgian society has heard about such a scenario.

Speculation has taken root that if Georgia joins NATO it would lose some of its territories. This isn’t a new notion; we’ve heard about this for a while now, probably since the time that Georgia first expressed its desire to join NATO. These speculations have had their effect, and fear has set in among the public, almost like a reflex, that entering NATO will mean losing territory.

It is probably for this reason that not a single member of the government of Georgia has publicly discussed this option. Mikheil Saakashvili’s government also avoided the topic after the idea came about sometime after the 2008 war.

The loss of land and territory is a sensitive and emotional topic, and many have trouble looking at the issue from a rational perspective. It is namely this sentiment which is used by those who oppose Georgia’s entrance into NATO by trying to inflate the possible negative consequences of such a decision.

What exactly is ‘Coffey’s scenario’?

Let’s take a look at what would actually change if Coffey’s scenario were to be realised.

Abkhazia and South Ossetia are currently occupied territories which are controlled by Russia, and it does not appear that Russia would be willing to relinquish control of them in the near future.

If Georgia enters NATO under the condition that the 5th article will temporarily be excluded and not cover the occupied territories, these territories will be no more ‘lost’ to Georgia than they are now. This fact will not change anything in the occupied territories – everything will remain as is: the international community believes, with very few exceptions, that they are integral parts of Georgia.

The rest of Georgia will be under NATO protection, with all the ensuing benefits – stability and development. And this development, paired with other factors, will increase the chances of the occupied territories returning. When these territories return into the fold of Georgia, they will also come under the protection of the 5th article in the NATO agreement.

It’s obvious that such simple and laconic arguments will not be able to ‘neutralise’ enemy propaganda, and it’s probably not worth arguing about it right now either as even NATO is not entirely ready for the ‘Coffey Scenario’.

More sceptical countries that were against giving Georgia the Membership Action Plan at the Bucharest summit in 2008 have not changed their position even now – they are still against discussing Georgia joining the alliance, and the variants and ideas that supporters of Georgia’s integration into NATO throw up to ease the process are of little importance.

These countries have their own arguments.

The arguments of sceptics

The main argument remains unchanged: Georgia joining NATO would anger Russia, and Europe is trying to avoid any further worsening of its relationship with Russia. For most countries in Europe, Russia is a neighbour from which they sense danger in a way that the USA simply doesn’t. The US, by the way, is the main lobbyist for Georgia’s integration into NATO.

The second argument is that under the conditions in which Russia is currently waging war in the largest country of Europe, Ukraine, and is threatening NATO’s most unprotected flank – the Baltic countries – the alliance simply isn’t ready for a new headache. At the moment NATO simply couldn’t afford to take on the protection of Georgia.

As for the USA, Georgia has benefited without a doubt from the support coming from Washington. The Heritage Foundation, which is a big player in American politics, published Luke Coffey’s article. The article is very positive for Georgia, but what can it change?

In 2008, the USA did all it could for Georgia to receive the Membership Action Plan, but this wasn’t enough. They were unable to convince the German authorities. What must the USA do now to change Berlin’s position on the subject?

Ten years have passed since the Bucharest summit, but Germany still hasn’t changed its opinion. Can it be changed at all? Probably not. Especially as Georgia is doing very little to this end.

Berlin is key

Over the past 12 years Georgia has been unable to appoint a strong and professional ambassador to Berlin. And that’s where Russia is very well represented in Germany by a powerful diplomatic corps. The past ten years have shown that it is impossible to influence Germany by work in Brussels and at NATO headquarters – some Georgian ministers have gone so far as to demand the Membership Action Plan from the Secretary General of NATO, who can only voice the agreed upon position of the members of the alliance, but cannot seriously influence them.

The key to Germany is not in Washington or Brussels but in Berlin itself, and nowhere else. Georgia is not doing enough work in Berlin (a lack of Georgian activity in other countries would fall under this description as well, but the main problem is still Germany).

Georgia must change its policy towards Berlin. Firstly, and this is the bare minimum, it must strengthen its diplomatic corps in Germany both in terms of quality and number.

Moreover, representatives of civic society in Georgia, such as journalists and political commentators, must be more active in Germany. They must actively work with their colleagues so as to ensure that the ‘Georgia matter’ be more strongly represented in the media and in non-state and expert circles.

These days the ‘Georgia matter’ is not on Germany’s agenda and it will continue in this fashion unless Georgia moves away from its inertia in this regard.

Who must take care of this issue? Nobody other than the Georgian government.

The activation of the Georgian media and the non-state sector in Germany will not be as expensive or costly so as to cripple the budget. But the problem is that the necessity of such actions is not yet recognised, which has resulted in lamentable outcomes.

It is pleasant to read articles such as Luke Coffey’s and of other writers who sympathize with Georgia, but such articles by themselves will not do anything.

I’ll say it again: ten years have passed since 2008.

Tornike Sharashenidze, professor at the Georgian Institute of Public Affairs