A Precarious Peace for Karabakh

The November 10 agreement could turn out to be a rapidly assembled construction that is not sustainable. Moscow may need wider international support to make it work. By Thomas de Waal at Carnegie Moscow Center

After weeks of bloody fighting in the new Karabakh conflict, everything happened suddenly, in the space of a few hours. The conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan was declared to be at an end, and in the middle of the night of November 9-10, Russian peacekeepers started arriving through the Lachin Corridor into Karabakh.

Only a short time before, Armenian leaders had been broadcasting the message that they were still fighting for Shusha, the hilltop town in the heart of Karabakh that they call Shushi.

Then Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan announced what was effectively a capitulation to Azerbaijan’s demands.

- ‘To have wished for war and now lament Russian peacekeepers is stupidity’ – commentary from Baku

- Military experts on Karabakh – turning points, preparedness and drones

- Op-ed: who will replace Armenian Prime Minister Pashinyan?

Pashinyan was fiercely criticized in Yerevan and he may not survive this crisis. But it is worth noting that this was a joint decision made with Karabakh Armenian leader Haraik Harutyunan. Harutyunan justified the decision by saying that the Armenian military was weakened by disease and poor morale, and the alternative was even worse.

“Battles were already taking place on the approaches to [the region’s capital] Stepanakert and if military action had continued at the same pace, then we would have lost the whole of Artsakh [the unrecognized Nagorno-Karabakh republic] in a few days and suffered heavy casualties,” he said.

The Armenian side is the big loser in this outcome, and the repercussions will be felt for years to come. The Armenian public was completely unprepared for this swift collapse and there is already strong resistance to the deal from opposition politicians.

But it is hard to see how, even if Pashinyan loses his post, the next Armenian leader could make a different decision.

It was swift, but it is also now obvious that this scenario had been well planned in advance.

For three years now Russia has been proposing to the conflict parties what became known as the “Lavrov Plan”–although its existence was always publicly denied. The essence of it was that there would be a phased withdrawal by Armenia from the occupied territories around Nagorno-Karabakh, and a Russian peacekeeping force would enter the region to guarantee the security of the Karabakh Armenians.

This went against the wishes of France, the United States, and other European countries for a multilateral solution to the conflict and an international peace agreement. It seems that Paris and Washington were taken by surprise by the announcement of the Russian plan.

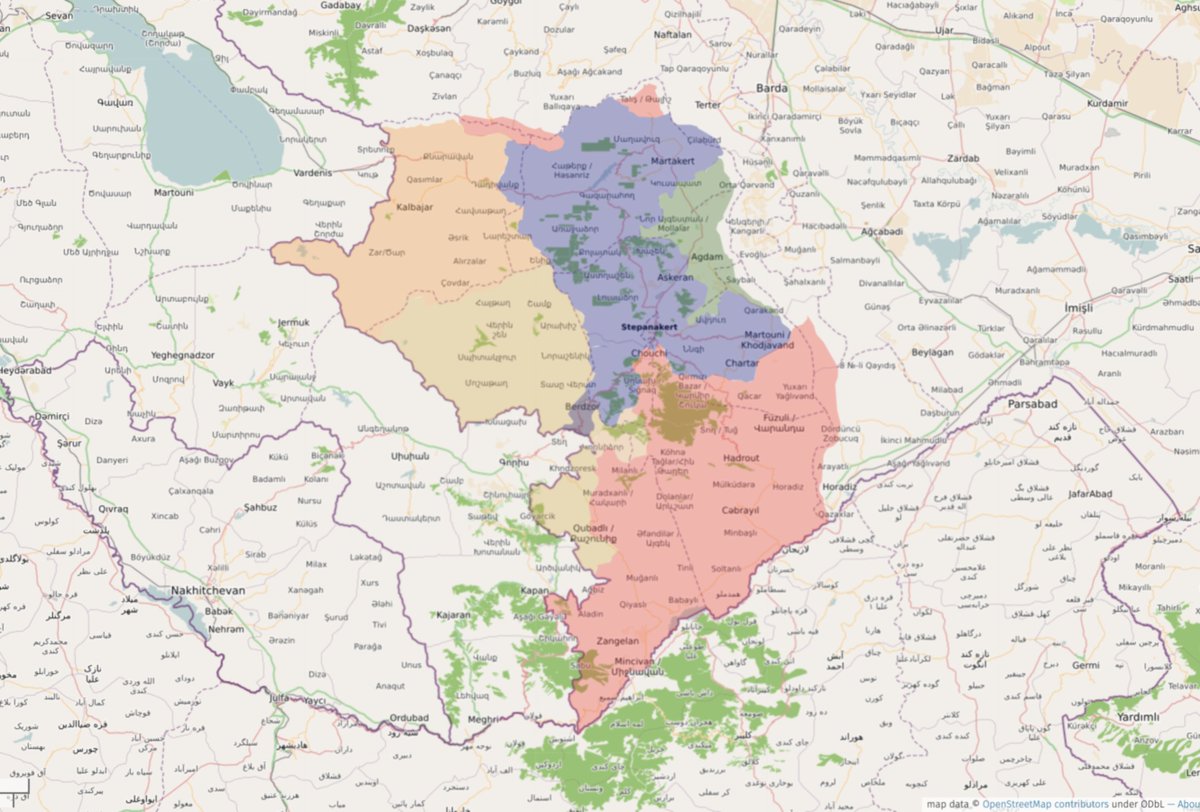

The core of the Lavrov Plan is now being implemented—but on much more favorable terms for Baku than before. A new line of contact is being established that runs through Karabakh itself. The Armenians are set to lose territory that includes a large part of the southern Hadrut region. Moreover, the status of Nagorno-Karabakh itself is not mentioned in the document.

Azerbaijan is the obvious winner. If President Ilham Aliyev were to run for election in a free vote tomorrow, he would almost certainly win by a landslide. He has suddenly got far more than could have imagined possible only a few weeks ago: the return of all seven territories around Nagorno-Karabakh, plus the town of Shusha.

We should expect to see Aliyev now pivot from being a public voice of aggression to posing as the voice of moderation, speaking a language of peace to the world. Some opposition voices in Azerbaijan will be asking why he did not try to recapture all of Karabakh, and why he allowed Russian troops into the region: something he is reported to have rejected at a meeting in Moscow on October 9-10.

The reasons for this are manifold. To attack Stepanakert would have been bloody and difficult and damaged Azerbaijan’s international reputation. Besides, it is highly likely that Aliyev did not want to have to consider, even theoretically, taking over Stepanakert.

Either the Karabakh Armenians would have been forced to leave, or he would have had to offer them a high degree of autonomy and change the constitution of Azerbaijan to accommodate a group of rebellious Armenians.

Far better to entrust responsibility for the Karabakh Armenians in a small enclosed territory to Moscow.

Turkey is also a big beneficiary. The main prize for Ankara in the nine-point deal is the promise of a corridor across Armenia’s Meghri region that would theoretically connect Turkey to Central Asia via Nakhichevan, the rest of Azerbaijan and the Caspian Sea. This resurrects a key ambition of both Azerbaijan and Turkey that was a central part of an unsuccessful deal for Karabakh negotiated in 1999-2000. It will be extremely difficult for Armenia to facilitate the building of this Turkic corridor across its own territory.

At first glance, Russia looks to have pulled off a stunning diplomatic success, after earlier appearing to have been outmaneuvered by Azerbaijan and Turkey. Yet what we see thus far is a one-page peace plan of nine points which is unclear on many aspects and will be very difficult to implement.

In the next few weeks, Russia must facilitate an extremely rapid Armenian withdrawal from the Azerbaijani regions of Aghdam, Kelbajar and Lachin (except for a five-kilometer “Lachin Corridor” connecting Armenia and Karabakh), regions Armenia has held for a quarter of a century. There are hundreds of Armenian settlers in these places, and there is likely to be resistance.

Moreover, the number of Russian peacekeepers inside Karabakh itself—fewer than 2,000—is fairly small to offer strong protection to its residents. Their mandate is subject to review in less than five years, which means that quite soon there will again be questions about the longer-term viability of the process. The more modest scope of the operation seems to be a demand of Azerbaijan.

The close geography of the region means that the two main population centers—Stepanakert, the main Armenian city, and Shusha, to which Azerbaijanis are expected to return—are right next door to each other. Some kind of contact between the two communities—for the first time since 1991—is unavoidable, and people will have to share the same road.

The nine-point plan envisages a new road being built from Stepanakert to Lachin, but the topography of the landscape makes that a major physical challenge.

It is also far from clear in the short term what the role will be of Turkish military personnel in the region and—in the longer term—how a new corridor across Armenian territory connecting Nakhichevan and the rest of Azerbaijan can be built.

Finally, there is nothing about the status of Nagorno-Karabakh in this agreement. This has been the issue at the heart of the dispute for more than a century. Leaving it out is deliberate, but it means that a highly sensitive political issue will remain unresolved.

In short, Russia has played a spectacular diplomatic move, but has also taken on great responsibility and will be blamed by both sides if things start to go wrong.

There is a chance that the November 10 agreement will turn out to be a rapidly assembled construction that is not sustainable. In particular, there are questions as to whether the Russian security deployment is robust enough to guarantee that Armenians of Karabakh can continue to live without fear in their homeland.

If many Karabakh Armenians displaced in the new conflict choose not return to Karabakh, that will be ominous, and could presage the continuation of the conflict in a new form.

For that reason, Moscow may soon decide that it cannot implement this plan by itself. In that case it is likely to remember its multilateral role and call for the support of the other Minsk Group co-chairs and the OSCE as a whole.

It can also call for help upon United Nations agencies, international organizations, and, very likely (and despite their major differences over Georgia and Ukraine), practical assistance from Western countries too. A wider United Nations peace agreement could be adopted to assert the principles of a long-term resolution of the conflict.

Some kind of peace is finally coming to Karabakh, but it is a very precarious one.