The refugee carpets of Karabakh

The carpets of Karabakh represent one of the four traditional schools of Azerbaijani carpet weaving. Following the Karabakh war these carpets joined the ranks of the ‘internally displaced’ and are currently housed in Baku and other Azerbaijani cities.

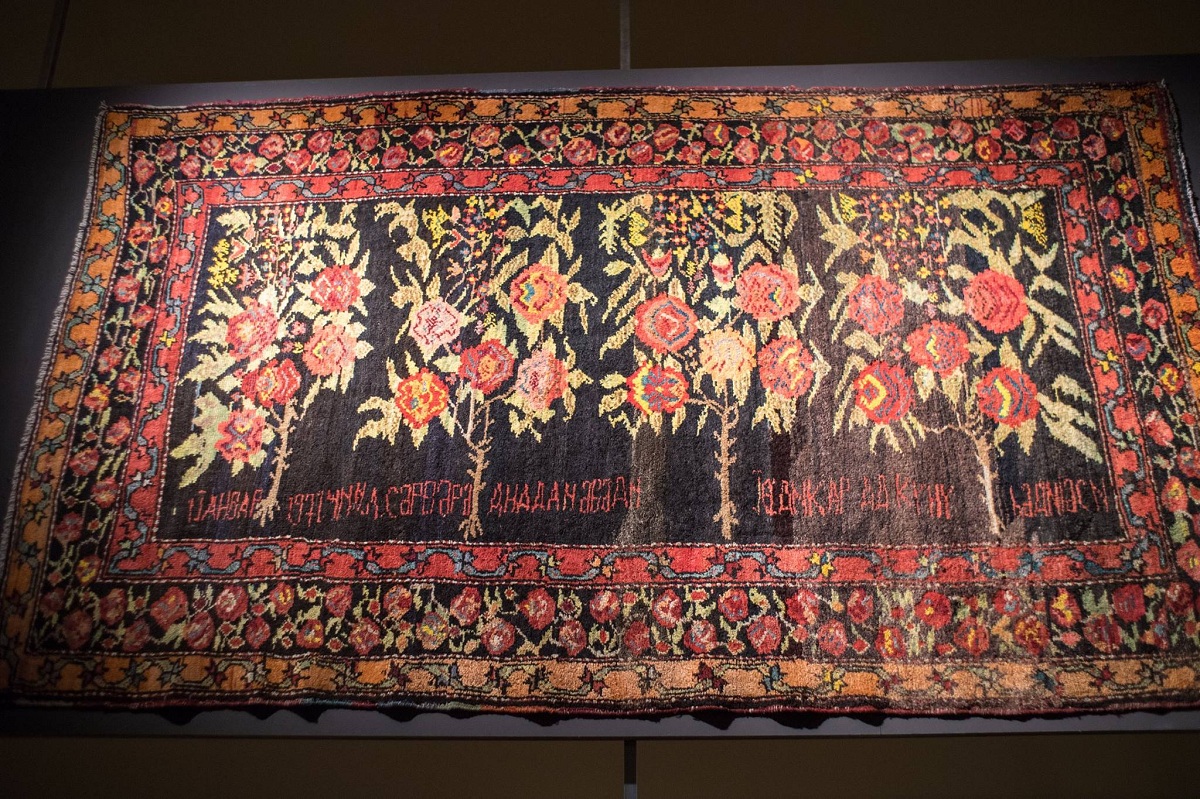

Before seeing some of the really magnificent carpets in the carpet museum in Baku, we take a look at this small carpet. It’s just forty-seven years old, not even an antique. From its appearance it could be 300 years old. Its ‘date of birth’ – 1971 – can be found along the bottom, together with a dedication in Azerbaijani: ‘For my son on the day of his birth’.

“Judging by the design, this carpet was woven by a woman from Agdam for her son”, explains the young guide. “It probably remained in the family but after the war, one way or another, ended up in the West. Then, somehow, an Azerbaijani living in Los Angeles, saw it at an auction and decided to buy it and return it to the owners. Unfortunately, he didn’t manage to find them and that’s how the carpet ended up with us. This is one of the most interesting examples on display – for its artistic merit, but also because of the family history it reveals.”

Carpets of flowers

The most distinctive features of Karabakh carpets are their bright colours and floral designs. The carpets are characterised by a profusion of magnificent blooms or, at the very least, an abundance of every imaginable colour, mostly dominated by crimson.

This is a general, initial impression, but a closer look at the carpets reveals dozens of different designs, many of which are named after the places where a particular pattern frequently occurred.

The carpets can be divided into four groups: those with and without medallion motifs, namaz carpets (prayer rugs) and pictorial carpets. In addition, Karabakh carpets were often woven as sets, rather than as individual carpets. Karabakh homes traditionally had very large rooms and so sets of five carpets (gyabe) were produced to cover the whole floor.

The Azerbaijan Carpet Museum includes a replica of a room furnished in the style typical of Karabakh in the 18th/19th century, with carpets, household items and furniture, and decoration on the walls in keeping with the carpets. It’s not a full size room, of course, but it is nevertheless homely and, according to those who know about these things, completely authentic.

A museum seeks refuge

The Karabakh carpets have now become yet another source of conflict between the Azerbaijanis and the Armenians. Azerbaijani weavers, historians, researchers and other people concerned with carpets accuse the Armenian side of appropriating Karabakh carpets and selling them, presenting them as Armenian. The Armenian side responds in kind, levelling similar accusations at the Azerbaijanis. Thus, as well as everything else that’s going on, Azerbaijan and Armenia are conducting a war of words over carpets.

Set apart from the other Karabakh carpets, another floor of the museum is home to the ‘refugees’ from a branch of the museum which opened in the Karabakh town of Shusha in the mid-1980s. It didn’t last for long – once the war began, the situation in the town steadily worsened until, in 1992, the museum administration arranged for a driver to come during the night and take away as many of the exhibits as possible under cover of darkness, driving without headlights. They managed to take almost all the carpets and most of the jewellery and embroidery items. The heavy and cumbersome copper dishes had to be left behind. And so the Shusha branch of the museum is currently housed in the Carpet Museum in Baku.

Karabakh carpets outside Karabakh

In 1992 a branch of the Azerkhalcha carpet producers’ association, which had been manufacturing carpets for domestic and other purposes since Soviet times, was also evacuated.

In fact, what happened can only metaphorically be described as an evacuation. Obviously, there was nowhere to take the heavy loom frames, but the workshop staff had to flee because of the war. In the end they didn’t go far, moving to the town of Barda (just a few kilometres from the frontline) into the building housing the local Azerkhalcha workshop. At first, the weavers and their families actually lived in the workshop itself and worked there too, continuing to make carpets. In time the refugees moved to live elsewhere but the workshop continued to function and is still operating today. Meanwhile there is now a new generation of craftswomen who have learned their skills partly from the experienced older women but also through vocational training.

The current head of the Shusha branch, Alisafa Nuriev, who has worked for Azerkhalcha for a long time, says a professional can tell from the way a carpet is made what sort of mood the weaver was in at the time.

“If I come into the workshop in the morning and notice that one of the weaver’s knots is too tight, it probably means the woman was feeling tense while she was working. It might be that there was some kind of conflict at home or that she was worried about something. And if the knot is too loose, the opposite is true – the weaver was feeling relaxed and her thoughts were wandering.”

Nuriev believes it’s possible to look at modern Karabakh carpets made outside Karabakh and tell the age of the weavers who wove them. Older women, refugees from Shusha and Agdam, who remember what happened in the early 1990s, tend, consciously or not, to weave darker carpets than the younger weavers who weren’t caught up in the war.

Such subtleties can only be perceived by the eye of someone with a profound understanding of the language of carpets. However, anyone can tell the difference between a homemade Karabakh carpet and a ‘factory-made’ one. The more asymmetrical and freestyle the design, the more likely it is that it was not woven to be sold and that it was not made in a workshop, but at home – for a daughter’s dowry, to mark the birth of a baby or just as a floor covering in preparation for the approaching winter.