Georgian medical workers on life and death in Covid clinics

The Georgian healthcare system was clearly not ready for this. Hospitals are overcrowded, ambulances arrive with enormous delays, and it’s hard to get ahold of your family doctor, too.

Medical staff in the country have found themselves in the most difficult of situations, working day and night, and having to put aside their families and are often risking their own lives to save others.

Several dozen doctors have already died in Georgia since the start of the pandemic.

We asked doctors from different regions across Georgia to tell their stories.

- Epidemic prevention a century ago in the Caucasus: wash your mouth with soap and don’t kiss your mother

- Georgia: strict new coronavirus restrictions until end of January 2021

Ketevan Shengelaia, 27, works in Tbilisi corona hospital

In July, I received a call from Gudauri (a ski resort two hours from Tbilisi). They had a lot of people in quarantine, they needed additional doctors.

I am an obstetrician-gynecologist, but there was no other choice. I went there immediately.

There was a chaotic situation on the ground. I had to manage about a hundred patients. Some had chronic illnesses, others had high fever. There were patients with heart failure, there were people who were experiencing panic attacks.

My colleagues there turned out to be the best epidemiologists, I was well trained to work with this virus. And in September I started working in Tbilisi – also in a hotel where people infected with Covid-19 were isolated.

All patients in the hotel are infected, but they have a mild form of the illness. Therefore, the most difficult thing now is for me to understand just when and if a patient needs to be sent to hospital.

Even with mild symptoms, patients are very anxious. The virus damages the nervous system itself. Patients listen to their own breathing, and panic they are dying.

A person may start asking to call an ambulance, and the doctor may panic. But this can mean that a really serious patient will lose the chance to get to the clinic.

In times like these, they need our support and support above all else to overcome their fear and anxiety. We have also become psychologists for our patients.

So I check all the time, ask a lot of questions, because everything is at stake. I cannot relax, I cannot rest. I can only think about not being wrong. I’m under a lot of stress.

It is also very dangerous to break the rules of what you’re supposed to wear. One small mistake and you yourself can become a ‘distributor’ of the virus.

Khatuna Getia, 48 years old, nurse at the clinic in Jvari, Samegrelo region

I remember the first time I had to put on a protective suit. It was in the evening, and we had to go to the Inguri bridge [the line of separation with Abkhazia].

We stood there with the patrol police, we were supposed to bring someone, presumably infected with a coronavirus, from the Gali district. But a test had yet to be done, we did not know the exact diagnosis.

Since then, this has happened many times.

We have everything you need to be protected when dealing with infected patients. But we are still very nervous.

Twice we’ve had a situation when a doctor has been too busy to come and we’ve had to decide whether to call an ambulance for the patient ourselves.

It was a great responsibility.

I had to decide whether to leave the patient at home or take him to the hospital.

In Jvari, about one in five people are infected. But most have a mild form and are treated at home. Therefore, there are still places in the hospital.

Darejan Khachapuridze, 59 years old, immunologist, head of the children’s department at the clinic Elgi and Company in Kutaisi

Our department is fully staffed, and we treat both children and adults. Over the past two months we’ve had 70-75 patients a day, many of them were severe, on average two or three are connected to artificial respiration apparatus.

There is no time even to sit down with anyone, and the nurses have the greatest responsibility.

Yes, the doctor prescribes treatment, but the result is highly dependent on the professionalism of the middle and junior medical staff, on their heroic work.

Quite a few people are actually being treated by my phone – they call, tell me their symptoms, I give them recommendations. And often I don’t even know who called.

I think we are not ready for all this. The situation is very serious. We are already at the peak of our capabilities, and I do not know what will happen in January when it gets very cold. I don’t know how we can handle this.

Gabriela, 29 years old, orderly at the Vivamedi clinic in Tbilisi

Nobody forces us to work with those infected with the coronavirus. A month ago, I myself said that I was ready to work with those infected with the coronavirus.

I used to work on other floors, but when I saw what a difficult situation it was, I decided to help the doctors and nurses.

The staff is small, there are many patients. Some say they can’t breath well. Others are nervous for just about any reason. We cannot stop even for a minute.

And one girl stood all day in the corner of the ward and cried. Finally, I came up and said: “Besides you, there are five more people here, don’t torture these people.”

One woman lay in a room for six people and all the time sniffed the food that was brought to her. She didn’t like one thing, then another, and she reproached me for that, although I explained that I didn’t cook this food, but only brought it.

Once, instead of the usual three slices of bread, they accidentally put two on her plate. She immediately asked me: where is the third? And I answered: the elections are over and now I have to be content with two pieces.

The entire room laughed, and so did that woman. Now this story has spread throughout the hospital like an anecdote.

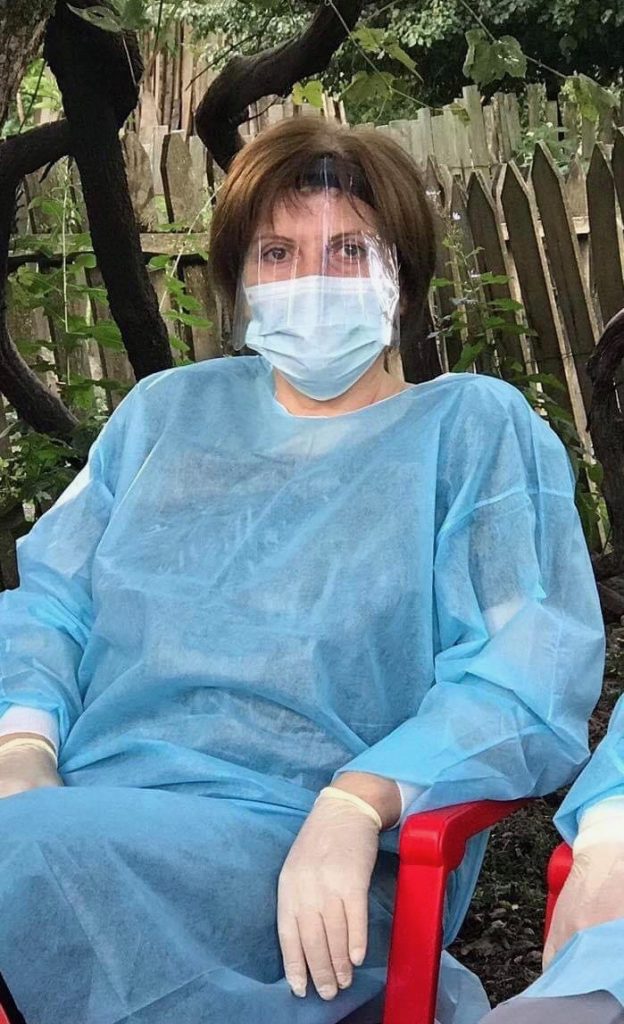

I work in a lot of clothes and the dressing procedure is complicated. First, gloves, then overalls, then change gloves, pull special plastic boots up to my knees, glasses, mask, shield, hat … And finally I can go into the ward.

I go in, distribute food, clean the room, and so on several times a day. I’m the only orderly on my floor. I work for two days and then rest for two days. I have my own room, and I sleep there for a while.

I get very tired. Sometimes I can hardly stand on my feet. But I still like what I do. I know that I help those who need it most.

And I’m glad I broke the stereotype. I am a transgender woman working in a clinic and caring for coronavirus patients.

One elderly man who was being treated here told me: you are busy all the time, you don’t stop, if tomorrow I meet you on the street, I won’t recognize you without this outfit. I smiled for myself and said: it doesn’t matter, grandfather, the main thing is that you get better.

Kakhaber Chomakhidze, 54 years old, resuscitator at the Center for Infectious Diseases, Tbilisi

At the moment, we are coping. We have the most severe patients here. In total, there are six beds: four are in regular intensive care, two are in the intensive care unit.

Sometimes we add beds and take 7 or 8 patients

The nurses and paramedics have been trained in how to put on and look after personal protection equipment. What’s new for us? Mainly the equipment. Otherwise, we treat patients as before.

When the first patients arrived, it was very emotional. We didn’t know what we were dealing with. Now we know much more about this disease, but we do not know it completely.

There are elderly people who have gone through the virus very easily. And a few young patients got very severe bilateral pneumonia. So even if you are at risk, this does not necessarily mean that everything will be bad for you if you become infected, and vice versa.

It also matters how many people around people have become infected with the virus – a million or 10,000.

I’m so used to the personal protective equipment that I can put it on and off in a minute, despite my age.

I have heard many times that people over 50 are at risk. But what should we do? Will someone else do my job for me? I chose this profession, now it’s my business.

I haven’t been home for two days, I really hope to go today. I live nearby and will return at night if need be.

In general, resuscitation is a special place. We don’t cure people – we drag them back into life. Most people take death seriously. And for me, this is the only thing I can’t get used to even after many years of working here.

Maia, a Georgian doctor in the Gali region of Abkhazia

The bridge across the Inguri, the border is closed [referring to the line of separation with Abkhazia, checkpoints of Russian and Abkhaz border guards – JAMnews].

Only very serious patients are allowed to be transported to the Georgian side, while there are a lot of infected people in Gali, and they are not treated in the hospital – they can only provide first aid. Several doctors from Russia work there and help local residents.

More than 50 percent of the hospital staff there are infected with coronavirus, and I also suffered the disease. Basically, everyone is treated at home.

A quick test can be taken free of charge, the only laboratory is located in Sukhumi. A computed tomography machine is also available only in Sukhumi, if necessary, a person must go by himself, often stand in line there.

Those who have no complications and are treated at home should buy the medicines themselves. They are available for sale, but they are very expensive.

But if the patient gets worse, everyone prefers to move to the hospital in Zugdidi, on the Georgian side. Therefore, people panic over the closed bridge.

But even there it is difficult, often the ambulance does not travel for a long time, there are no empty seats in the hospital.