Once again, oil-related sicknesses

Both the economy and politics in Azerbaijan are largely dependent on oil. Abrupt changes in the oil market over the past year and a half had a serious and negative impact on the economic situation, but have not actually led to any changes in public management.

A brief history of the oil-dependent economy

The Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan (BTC) oil pipeline, officially put in use in July 2006, is the main source of the country’s oil revenues that replenish the state budget and the Oil Fund. In this sense, Baku sort of drew the ‘winning ticket,’ since the start of oil production for Europe miraculously coincided with the rapid growth of its value.

Azerbaijan’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP) increased by 2.5 times during the period from 2003 to 2008. And the most serious growth occurred in 2007-2008. In 2008, Azerbaijan exported $47.7 billion US worth of products and over 88% of export accounted for oil and associated materials (gas, and, to a lesser extent, mazut).

According to official data, the poverty rate (the number of people living below the poverty line) in the same period dropped from 45% to 11%.

In the reported period, the number of employees who received their salaries from the budget increased in Azerbaijan (similar to in neighboring Russia). In 2014, the number exceeded 900,000 despite the fact that the official number of people employed in the private sector was slightly more than 600,000.

In 2012, a public servants’ average salary amounted to 447 AZN (approximately 440 EUR), though the employees of certain ministries received bonus salaries in ‘envelopes’ (the amount was in cash, so that they avoided paying taxes).

At the same time, there was an increase in the number of ministries and agencies, as well as the increase of the available staffing pool – as of early 2013, the overall number of public servants totaled 29,200 people (this number was 26,000 in 2010); their average official salary increased to 464 AZN that same year, then in 2014 it became 617.6 AZN.

According to that year’s data, 58.6% of the economically active population were employed in the public sector.

The oil price remained high that whole time, until July 2014. The Crude Oil Brent price reached its plateau in July at $112 US per barrel, while the more expensive Azeri Light even reached $130 US. After this there has only been drops in the oil prices (to be precise, in the average monthly indices).

In February 2015, the oil price reached its low in recent times, $54 US (the last time it reached this point was in 2009). And that’s when the first decline of the Manat occurred, which had been ‘predicted’ by economists six months prior (when the tendency of dropping oil prices began).

Despite all the assurances of ‘unrivalled growth,’ Azerbaijan’s oil-dependent economy began experiencing troubles as early as 2010. On the one hand, in 2007, Azerbaijan experienced an unprecedented 24% growth in the GDP in the span of a year. However, this growth was entirely related to the introduction of the Baku-Tbilisi-Ceyhan pipeline.

This production growth, just as it was gaining momentum, ceased as early as in 2010. Whereas in 2011, GDP growth was just 0,1%, despite the fact that the average global GDP growth that year amounted to 5%. In other words, the economic development of Azerbaijan in comparison to other countries, on the whole, was poor.

.jpg)

The crisis

Apart from oil, the country’s economy was characterized by two major factors: the service sector and construction. Throughout the entire oil period, there was a continuous ‘drop’ in Azerbaijan’s agriculture (starting from 2005, when, according to the State Statistics Committee’s data, a decline in agricultural production was 1% lower than previous year), as well as in other industries not related to oil or construction.

At the same time, there was an unprecedented influx of the population in Baku. Quite tellingly, the demographic indices of both the population size and migration are clearly inconsistent with the reality of the situation.

According to UN data (obtained from governmental sources), the population in Baku increased from 1.8 to 2.1million during the period from 2002 to 2012. Meanwhile, the 2009 population census was, in reality, never conducted. One can confirm this by asking their acquaintances: no one came to them with questionnaires.

Moreover, the population growth during this period was sparked by the increased housing construction in the city, which certainly isn’t a reliable indicator.

Thus, the Manat depreciated by 34.5% in February 2015. Coupled with a drop in budget revenues, it had a serious impact on the economy. There was a 9-fold drop in car imports during the last year alone. The real estate market also experienced a similar decline. The banking system was seriously affected.

One in ten employees of the financial sector lost their jobs in HY1, in 2015 alone. The number of problem loans (i.e. the number of debtors incapable of paying off their arrears on time) increased by 38.7% in the first 9 months of that year.

Many banks either went bankrupt or lost their license in the current period, officially due to the low capitalization rate.

.jpg)

Responding to the crisis

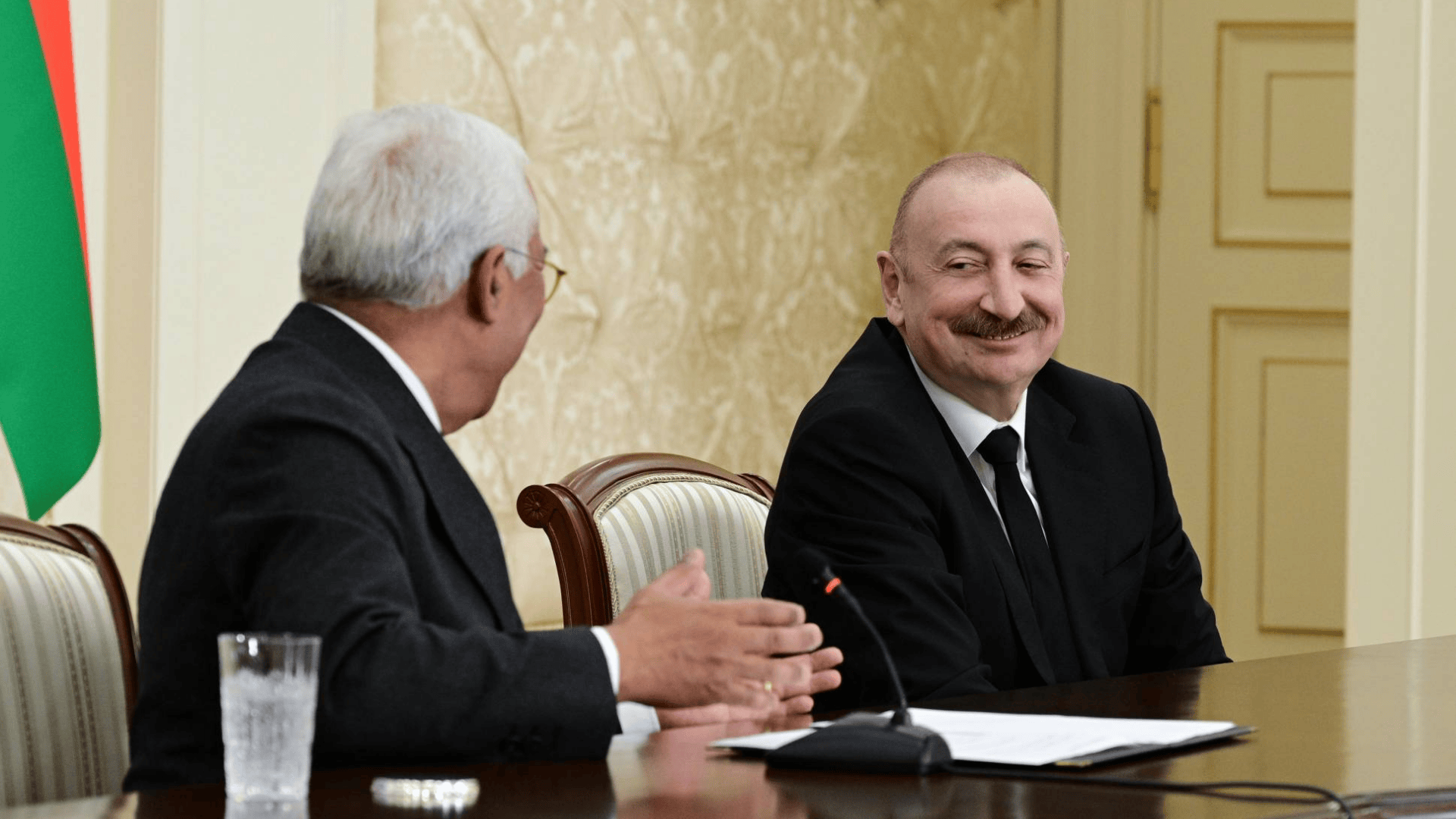

In February 2015, President Ilham Aliyev first spoke about the need for the diversification of the economy and that it was necessary to quit being oil dependent. Since that time, this idea has been voiced by him at almost every session of the Cabinet of Ministers.

Throughout this period the state has not actually taken any real steps to improve the situation. Some ‘cosmetic’ measures were taken instead, and shortly thereafter, many of them were canceled.

In particular, under the President’s decree, the sale of alcoholic drinks for cash was banned starting in January 1, 2016. As a result, all spirits disappeared from store shelves on New Year’s Eve. The ban was lifted 12 days after its entry into force.

Since the beginning of the crisis, independent economists have been repeatedly pointing to the need for introduction of an anti-crisis program (similar to the program existing in one form or another, with all of its advantages and drawbacks, in oil-dependent Russia and Kazakhstan).

It was only on March 16 that the President signed a decree on the approval of the ‘Key aims of the strategic roadmap of the national economy and the main sectors of the economy.’

‘Local and foreign experts, field specialists, consulting companies and research organizations can get involved’ and be part of the project. Under the decree, development projects for each sector of the economy should be determined in a four-month period.

The process of decision-making on important economic issues in Azerbaijan apparently has two major features-closedness and slowness. It is unclear, which particular interest groups influence these decisions and how. But the obvious thing is that some of them seriously hamper their implementation.

However, in view of oil market dynamics, there is no reason to believe that the situation will be the same as it was and that the oil price will return to the 2010-2014 level. For example, Standard & Poor’s has predicted that the oil prices could be back up to $50 US per barrel even by the year-end.

In addition, European consumers (the main client of the Azerbaijani oil) will cut down on the consumption of natural fuel (including gas) in the long run.

In this light, Azerbaijan really has no reasons to delay reforms. But since it obviously does so, it gives one grounds to think that the reason for this delay are the strong interest groups, and possibly officials, who monopolize entire sectors of the economy.

These activities can be confirmed by the wave of arrests of government officials and prominent businessmen, which had never been seen during the past decade. Reduction in profits and the need to downsize expenses (including budgetary ones) have apparently resulted in a serious struggle within the so-called elite.

Throughout the year, ministers and their aides, including the National Security Minister, Eldar Mahmudov, were dismissed from their posts. His deputies ended up in jail for racketeering. Jahangir Hajiyev, the Head of the International Bank of Azerbaijan (the country’s largest bank), was sent to prison for the misappropriation of funds amounting to approximately 1 billion AZN. Nearly all prominent businessmen, participants in the aforementioned state-run projects, were arrested in May last year.

Among the arrestees was Ibrahim Nehremli, the founder of the largest and most ambitious project in Azerbaijan’s history – Khazar Island (an artificial island comprising of imported vegetation plantations and a chain of restaurants, hotels and entertainment centers).

The total project cost was estimated at $2 billion US and, quite tellingly, this project (like many others) was not completed.

Judging by the outcome, in the post-oil period, the actors influencing the decision-making processes have been preoccupied more by the rearrangement of the income sectors of the economy, rather than by rescuing it. And so far, there are no actual reasons (no actions have been taken by the state yet) to assume that the vector of the Azerbaijani economy is likely to change and become more of open and diversified.

.jpg)

Data for this material has been taken from official sources: the Central Bank of Azerbaijan – cbar.az, the State Statistics Committee-stat.gov.az; and the press-1news.az, trend.az, contact.az, day.az.

The opinions expressed in the article convey the author’s terminology and views and do not necessarily reflect the position of the editorial staff.

Published: 20.05.2016