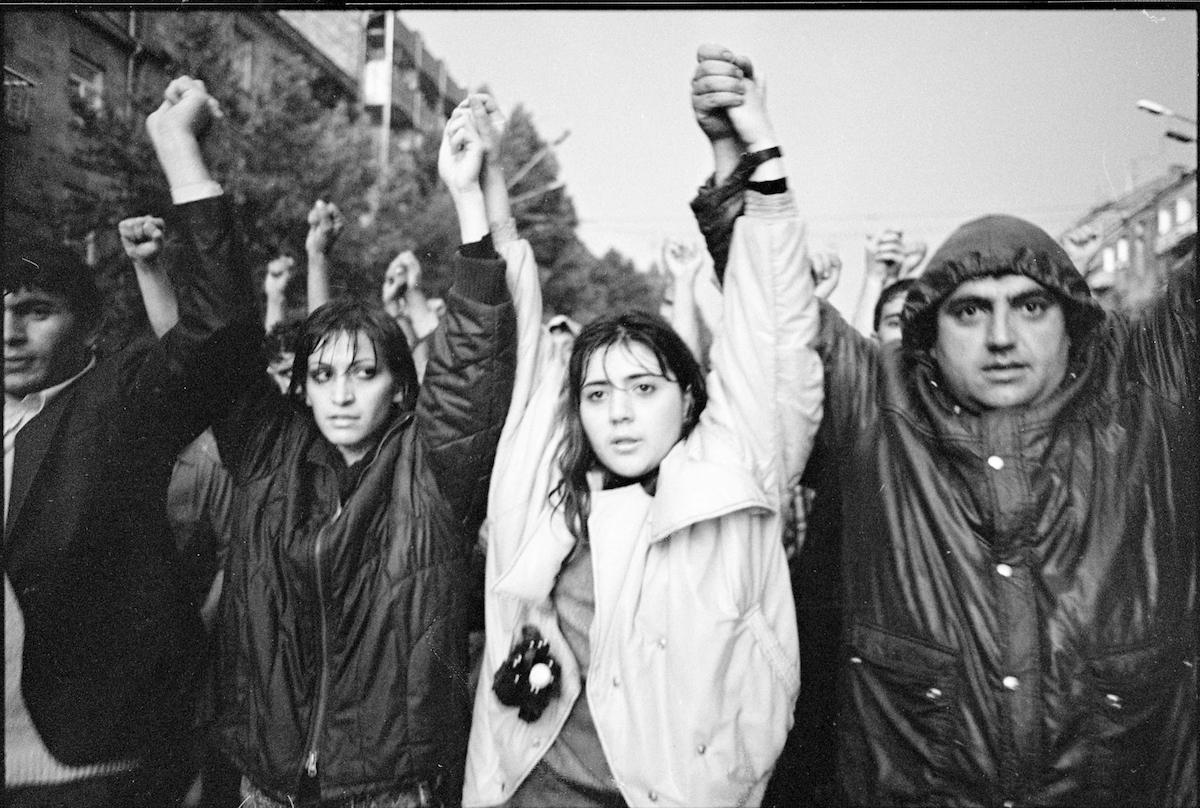

My Karabakh - Part III: Summer of 1988 - Yerevan demands that Karabakh be returned

This is the third story in the ‘My Karabakh’ series written specially for JAMnews by Armenian journalist and writer Mark Grogorian.

Karabakh stories, all parts here

was 1988, the Karabakh demonstrations were in full force in Armenia, and all of my friends and acquaintances had been dragged into it in one way or another.

But as time passed, I noticed that they all had different points of view on the matter.

Some saw the conflict as a purely territorial dispute about the right to land in Karabakh: as if it was a region where there were no people, and people weren’t important, but the land was.

Others saw a religious standoff – the ‘eternal’ argument between Christians and Muslims.

Some others said that it was namely Karabakh that would decide the fate of European civilisation, because it was Karabakh that was the last stronghold of pan-Turkists on the road to world domination.

And the pan-Turkists, as everyone knew, thought only of destroying Armenia, which in turn was supposedly bent on preventing them from doing so with their evil plans and conspiracies.

Like many in Armenia, I saw the issue of implementing historical justice as a matter of overcoming the inheritance of Stalinism. And if that’s the way things were to be, then it was Moscow that had to act, and act quick, because that’s what real perestroyka [lit. restructuring; perestroyka was a political movement within the Communist Party] is.

In those days, they started talking about the national liberation struggle, about the ‘Leninist’ right of the nation to self-determination. The slogan ‘Lenin-Party-Gorbachev’, and its antithesis, ‘Stalin-Beria-Ligachev’ became popular (the latter being a symbol of a conservative politician at the very top of the Communist hierarchy).

Evidently, these slogans were a way for the Karabakh committee – which was at the helm of the demonstrations – to let the Kremlin know without a doubt what its position was: we’re loyal to Moscow, but Karabakh must become a part of Armenia.

Karabakh movement, which had become for me and many others in Armenia and Azerbaijan one of the most important symbols of 1988 and which began as a series of pro-Moscow demonstrations, soon turned out to be the first nail in the coffin of the Soviet Union. And it changed forever the lives of not only our two republics. In fact, this year changed the entire country.

And consequently the entire world.

‘Nstatsuyts’, or the sit-in demonstration

But let’s get back to the beginning of the summer – or rather, to the end of spring.

The demonstrations on the opera square had become an everyday event. They took place regularly, and generally brought together – what seemed to me – from six to fifteen and sometimes up to twenty thousand people.

At the demonstrations, people received information and exchanged opinions. What was said at the meetings quickly became the truth for many Yerevantsis.

The television ceased to be a source of trusted information. However, every programme on Moscow television which spoke about Armenia or Azerbaijan or Karabakh was thoroughly discussed and found lacking.

It was rare for societal opinion to assess a programme as ‘not bad’ and even rarer for someone to say ‘good’.

Gradually, the addressees of the demonstrations changed. In February, the demands of the demonstrators concerned Moscow, the Center, the Kremlin and the Central Committee of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union.

But by the time summer had come around, the demonstrators were addressing the leadership of Armenia.

The logic was such: if the Council of People’s Deputies of the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, in complete accordance with the legislation of the USSR, were to address the Supreme Councils of Azerbaijan and Armenia with the request to agree to the transfer of the entity from one ‘brotherly’ republic to another, then why should the Supreme Council of Armenia not examine this request?

Consequently, it should be examined and accepted. And when Armenia accepts it, Azerbaijan will of course object, at which point Moscow will have to join in the fray as an arbiter and, well, we’ll just have to see what it decides.

Nota bene: in the first months of the Karabakh movement, Azerbaijan was not even addressed at the meetings. There was no attempt to strike up a dialogue, not with Baku nor with the democratic forces or dissidents in Azerbaijan.

Instead, the protesters first sought Moscow’s solutions, and then Moscow’s decisions, but as a response to the actions of Yerevan.

How can this be explained? Well, on one hand, the demonstrators believed there was no way a conversation would work out. And on the other, there was a common understanding: “What is there to talk about [with Azerbaijanis]?”

There was yet a third element: there was no tradition of holding a dialogue through official channels between neighbouring republics. Everything went through Moscow. However, there were of course contacts between officials, and for the ordinary people often entirely friendly relationships. Mixed marriages were common, Armenians and Azerbaijanis visited one another and peacefully lived in the same neighbourhoods.

They sold and bought things from one another. And of course, they fought and beat one another. How could things be otherwise?

But let’s get back to the opera square.

monotonous flow of demonstrations were broken up, if my memory serves me well, in the middle of May, when a group of students sat down on the steps of the opera and announced that they would not get up until Armenia would make an official decision and accept the request of Karabakh.

The number of students that joined in on the sit-in strike soon grew to about 200 people.

This was a rather unexpected form of protest which gave the Yerevan demonstrations a well-needed streak of youth.

People started gathering around the students. They were visited by well-known singers and actors, who came to entertain and chat with them. The musicians came with their instruments and played for them.

Those on strike were fed by all of Yerevan. It was considered good form to go to the square, having taken something tasty from home to give to the protesters, or at least to bring them a thermos with tea or coffee.

The sit-in protest was a rare case in the USSR of a large-scale protest achieving its aim. The recently appointed First Secretary of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Armenia Suren Harutyunyan gave way to the demands of the protesters and on 15 June the Supreme Council of the Armenian Soviet Socialist Republic passed a resolution to make Nagorno-Karabakh a part of Armenia.

That period, May – June of 1988, is remembered even now as ‘the time of the sit-in protests’. A number of those who emerged from those student protests as leaders even now play a significant role in the life of Armenia, having become state officials, diplomats and journalists.

But for one of the students, Nairi Hunanyan, the strike was a defining moment. After the strike he disappeared, and next appeared in the eye of the public 11 years later, on 27 October 1999, when he headed up an armed group of five people who stormed the parliament.

They killed the Prime Minister of the country, the chairman of the parliament, two deputies, several members of the parliament and a minister. They brought about a deep political crisis by striking at the very core of Armenian statehood.

Hunanyan is now serving a life sentence in prison.