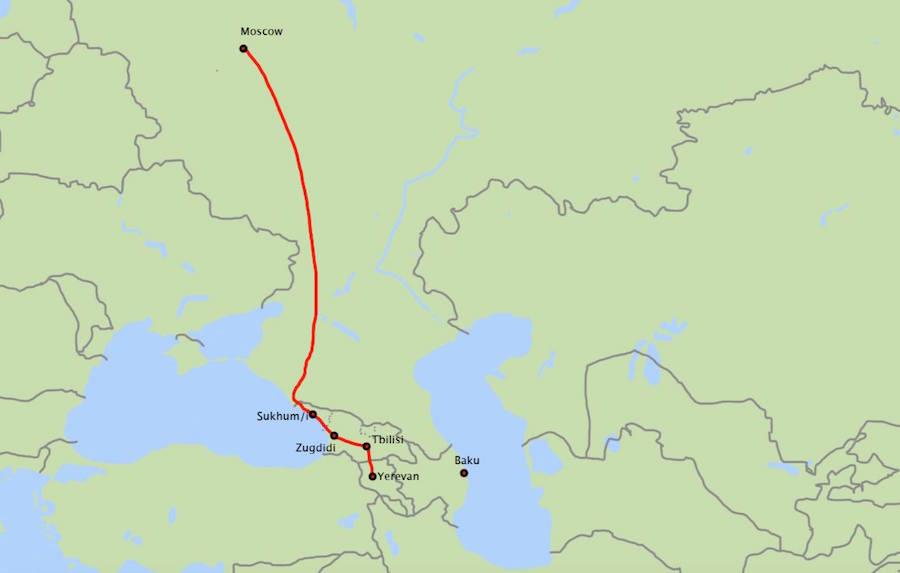

Trans-Caucasus railway: Moscow-Sukhum/i-Tbilisi-Yerevan - no beginning, no end

Trans-Caucasus railway: Moscow-Sukhum/i-Tbilisi-Yerevan

A theoretical possibility of restoration of the transit railway communication from Moscow through the Caucasus and then further to Turkey and Iran, has been periodically a subject matter of active public debates in these areas over the past few years.

The opinions fundamentally vary, from lobbying this hypothetical project to its strong and outraged rejection.

A non-existing and therefore ‘mythical’ Moscow-Sukhum/i-Tbilisi-Yerevan railway project has once again appeared to be in the thick of disputes, this time in Georgia and Armenia.

During his visit to Georgia on February 23-23, Armenian Prime Minister, Karen Karapetyan, told journalists as follows:

“If you are interested, whether there will be any alternative to Lars [a border crossing on the Russian-Georgian frontier, the only overland route from Armenia to Russia], let me assure you that there certainly will be! The details will be made public later, I’m not going to expand on it so far. We’ve reached an agreement on both, the Lars and the energy corridor.”

The Armenian Premier’s words stirred up protest in Georgian opposition, which blamed Georgian leadership for being engaged in behind-the-scenes talks on restoration of the railway traffic through Abkhazia, which opposition flatly disagrees with.

Georgian Vice-Premier, Kakha Kaladze, in turn, stated that there were no discussions on the railway issue with the Armenian delegation and the Georgian government didn’t even consider that issue. Zurab Abashidze, Georgian Prime Minister’s Special Representative for Relations with Russia, also denied the aforesaid reports.

Upon the Armenian delegation’s return home, none of the Armenian officials mentioned any agreements with the Georgian side on transit issue either.

So what’s the railway that causes scandals, enthusiasm and broad debates with varying degrees of success?

JAMnews special investigation

The Trans-Caucasus Railway: neither the beginning, nor end

Trains en route from Moscow to Yerevan stopped operating twenty-three years ago as a result of the Georgian-Abkhaz conflict. Throughout the years following, any discussion on the possible revival of railway traffic ended up in a political stalemate.

In 2012, a new government came to power in Georgia. It was on its initiative that the question-what about restoring the Moscow-Yerevan railway?-suddenly was back on the agenda. Yet, it still remains a big question mark.

Tbilisi: A premature talk

Kheta village is situated 20 kilometers from the town of Zugdidi in Western Georgia. The old railway station there looks more like ruins with broken glass, twisted shutters…and there are no doors at all. An inscription ‘Booking office’ has remained on one of the premises. A cow is strolling freely in the station area.

Tbilisi-Zugdidi passenger train passes through Kheta village twice a day.

Kheta station today

Kheta station today

‘Earlier, in Soviet times, it was a different matter-there were Tbilisi-Moscow, Tskaltubo-Moscow and Yerevan-Moscow trains. We have a big village and all of the trains stopped here. I sat in the booking office, selling tickets all day long.

About fifty people were employed at our station,’ says Lamar Janashia, who has worked here as a cashier for 40 years.

‘The young generation does not remember that. Whereas earlier, the children would line up along the railway to wave at passengers. Tangerines and bay leaves are cultivated in our village. Railcars full of them were sent from here to Russia. ‘

It all ended 23 three years ago, when the Georgian-Abkhaz armed conflict in 1992-94 began, concluding with the declaration of independence of Abkhazia, not recognized by Georgia to this day.

A dispute over the status of Abkhazia, the independence of which was officially recognized by Russia following the August war in 2008, is a major obstacle for the restoration process of the railway.

During Mikheil Saakashvili’s presidency, when Georgia’s relationship with Russia dramatically worsened, especially after the conflict in 2008, discussing the railway issue was out of question.

After coming into power in 2013, the “Georgian Dream’ party, led by new Prime Minister, Bidzina Ivanishvili, started making efforts to normalize relations with Moscow.

Just two months after his appointment as the Prime Minister, during his official visit to Yerevan in January 2013, Ivanishvili stated that the railway issue could be resolved if there “is will from all the parties. Yet, he admitted that it would be a slow process.

The Georgian Prime Minister’s aforesaid statement fueled discussions in Tbilisi.

The opposition and some experts blamed Ivanishvili for neglecting Georgia’s national interests, as well as for ignoring the interests of Georgia’s key economic partner, Azerbaijan.

Then-President, Mikheil Saakashvili, was also among the critics:

‘This railway will be the springboard for Russia to conquer the Caucasus, gaining influence over Armenia and Azerbaijan and giving it access to Iran. Why has Georgia been turned into a pawn in Russia’s cheap game?’ said Saakashvili.

‘If the Abkhaz section of the railway is restored, where will the Georgian border guards be stationed? If the Abkhaz railway is not restored at the same time as their de-occupation of Georgia, then it will just legitimize Russia’s occupation of Abkhazia.’

Saakashvili claimed that Georgia, instead, should focus on east-west railway traffic, from Azerbaijan to Turkey.

The potential economic benefits to Georgia of resuming railway communication between Russia and the South Caucasus are quite obvious.

The pipelines and railroads linking Azerbaijan, which is rich in oil resources, to western markets, already pass via its territory and restoration of railway transit with the north would strengthen its role as a regional transportation hub.

Paata Zakareishvili, former State Minister for Reconciliation and Civil Equality, underlines these advantages: ‘Everyone can benefit from this railway-Russia, Georgia, Armenia.

This will enhance the country’s role as a transport corridor and increase its geopolitical importance. Cargo will be transported not only east-west, but also north-south.’

However, many economists believe that the restoration of the railway is less likely to have a significant economic impact, since it will, first, lead to a drop in commodity turnover via the Poti port and, secondly, may theoretically take away a portion of shipments from Baku-Tbilisi-Akhalkalaki railway.

Third, it will cause Azerbaijani discontent, which could affect Georgian-Azerbaijani relations in the energy field.

MP Sergi Kapanadze, a former head of the Georgian Reforms Association (GRASS), claims that ‘Georgia’s economic, energy and even political independence depend particularly on infrastructure projects bypassing Russia and strengthen Georgia’s role in regards to the functionality of its regional transit.’

Apart from the economic benefits, the railway issue can bring Georgia political dividends, too. For example, it is possible to consider this question in conjunction with the problem of the refugees’ return to Abkhazia. However, at this stage, it completely rules out the possibility of commencing talks, since the Abkhaz side will definitely not agree to that.

Sergi Kapanadze believes that restoration of railway transit is impossible and that this idea is premature.

‘Restoration of the Abkhaz section of the railway can theoretically be profitable. But it’s too early to discuss this issue. Before that takes place, Georgian authorities should have the answers to several questions:

• What kind of cargo will be transported on this railway? Will it be military or just civil?

• What would railway traffic between Abkhazia and the rest of the territory of Georgia be like? Should there be stops along the way or it should it be non-stop transit?

• Who will ensure the safety of goods in the territory of Abkhazia?

• What parties will come to an agreement on the restoration of the railway?

• Will there be an agreement between railway companies or between the countries involved?

• How will Azerbaijan benefit from this project?

• What impact will this route have on the Baku-Kars railway line and Georgian-Azerbaijani relations, generally speaking?

• How will the traffic on this railway be organized? Where the custom officers stand? The border guards?’

Sukhum/i: Impasse Economy

If a journalist or tourist traveling in Abkhazia wants to highlight the postwar havoc, abandoned railway stations and railway tracks, overgrown with weeds, will definitely turn up in his photo report.

Although the number of deserted areas in the country has recently decreased, the Abkhaz railway infrastructure remains a sort of ‘oasis’ by virtue of the hopeless economic conjuncture.

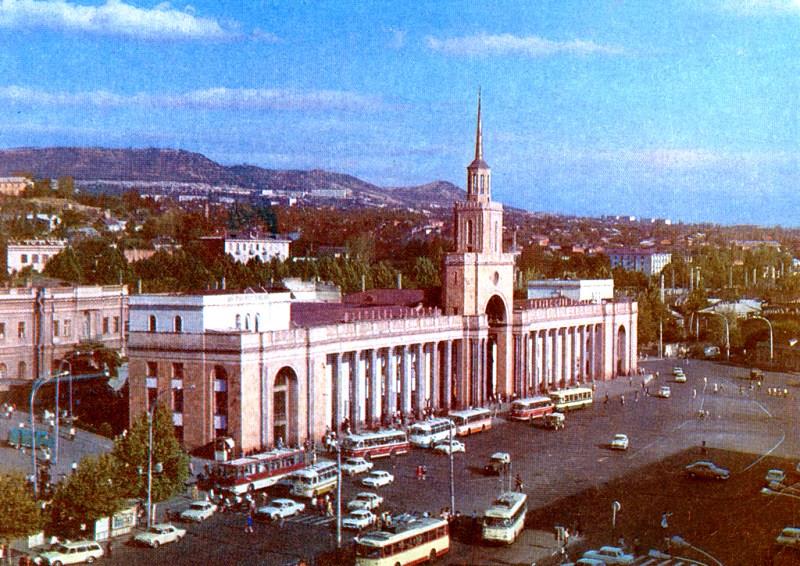

However, some of its segments may still be revived from the ashes, for instance, the Sukhum/i railway station.

Built in Stalin empirical style, this grand building seems to have drawn a winning ticket. It would have languished in poverty if it had not been for some Russian philanthropist, who, wishing to stay anonymous, recently proposed to reconstruct it at his own expense, without seeking any profit.

‘My grandchildren will be proud as they look at the station rennovated by their grandfather.’ That’s how he describes one of his incentives to participate in this quite costly project.

There is just one question that is bothering both inhabitants and officials: how can the imposing building be used and what can done with it? It can serve the railway traffic, as it does now-one daily train from Russia and a couple of cargo trains a week-a small outbuilding next to an abandoned railway station is quite enough for that.

For 23 years, that is, since the beginning of the Georgian-Abkhaz war, this railway section has been a mere deadlock. Who is interested in Abkhazia’s tiny market?

The Abkhaz railway had a spark of hope after Sochi had won the right to host the Winter Olympics in 2007. The major construction required gravel and sand in bulk and Abkhazia expected that Russia would use its building materials.

With these plans in mind, the government even took a two-billion credit from Moscow for the reconstruction of the railway from the Russian-Abkhaz border to Sukhum/i.

However, these dreams did not come true. Though the credit was received, it was utilized in such a way that the mere memory of it still makes former and new government officials alike shudder.

The time has come to pay off debts, but there is no money in the budget. An act was not signed even during Alexander Ankvab’s presidency, since executing the job amount to a mere 1.5 billion RUB, with the published stated totaling 2 billion RUB.

And the quality of repairs is far from being perfect. At certain sections a train driver still has to drive at 20 kilometers per hour–the condition of the railway track does not permit higher speed.

Guram Gubaz, the head of the “Abkhaz Railway state-run unitary enterprise, admits that the only chance to revitalize this area is to open it to through traffic with the South Caucasus nations.

‘In the late ‘80s, forty pairs of trains passed through Abkhazia daily. If the railway had even half of that traffic now, we would not have any problems maintaining such a large economy and paying salaries to employees.

The company would stand firmly on its feet. Furthermore, the state budget would be in a much better state,’ he claims.

‘Any railway can bring in some income if train traffic is frequent enough, i.e. if it is a transit railway, and also if there is a sufficient amount of exports. Unfortunately, nothing of the kind is expected today or in the near future, since it’s unlikely to presume now that Georgian will recognize us, says Akhra Bzhania, MP.

The issue of reestablishing through traffic is raised from time to time. However, it depends greatly on politicians that consideration of the problem never goes farther than discussions. In particular, there are problems with the registration of cargo documents when crossing the Georgian-Abkhaz border.

Georgia does not recognize Abkhazia and, therefore, it is fervently against Abkhaz border guard and customs officers’ involvement in inspection and clearance of goods on the territory of Abkhazia. The official Sukhum/i, in turn, is not ready to make such a concession, since it regards it as a violation of its sovereignty.

However, the main obstacle still lies within the economy. On the one hand, despite the repairs being done on Russian money, the Abkhaz section of the railway has not been fully restored. Trains can go only from the Russian border to Ochamchira.

There is no railway as such from Ochamchira to the Georgian border. Not only have the rails been taken for pieces for scrap, but rotten crossties have been stolen on certain sections. as well. In addition, it is necessary to restore several bridges, which were blown up during the war.

According to experts’ estimates, about $200 million US is required for the full restoration of through railway traffic.

In 2012, the International Alert organization studied the potential economic benefits of the through railway traffic restoration project.

“We put aside the political component and examined only the economic aspect. That is, we tried to determine which tracks could theoretically be used in railway transit would resume, says Beslan Baratelia, an economist.

“Alas, during construction, we came to an unpromising conclusion: in light of the present condition of the economy in all parts of the South Caucasus, transportation of serious volumes of cargo on this railway is out of the question.’

The production capacity of these three regions is such that even if the entire volume of their produce is exported to Russia, the railway load may be only a quarter of that of the pre-war amounts.

‘In view of the fact that the Transcaucasian republics had bordered Iran and Turkey, this railway had strategic importance in Soviet times. Substantial volumes of military cargo were transported via it. In addition, oil products were transported from Azerbaijan to Russia in bulk. Industrial giants were operating in the region.

The economic plans of those times contributed to the growth of industrial production, and consequently, there was a growth in the number of products transported by this railway. Furthermore, there was a huge number of passenger trains moving in this direction. There is nothing left now,’ says Guram Gubaz, Abkhaz Railway director.

Baku: Far from being relevant

Baku certainly does welcome the restoration of railway traffic between Russia and Armenia, but this issue is unbelievably far from the current agenda being addressed in Azerbaijan. The last time it was mentioned in the printed media was in 2014. Experts, interviewed by JAMnews, do not believe it will be restored.

Ilgar Velizade, a political analyst states: ‘This issue has not been raised since the 2008 war. It was the Georgian State Minister, Paata Zakareishvili, who brought it up for the first time in years, after the ‘Georgian Dream’ coalition had come to power in Tbilisi.’

Baku nervously responded to that statement, since the new Prime Minister, Bidzina Ivanishvili, also talked about plans to restore railway transit with Abkhazia, linking this issue with the possible introduction of direct railway traffic not only between Russia and Armenia via Georgia, but also possibly extending all the way to Iran, which would noticeably weaken Armenia’s blockade and would not exclude the possibility of the transportation of military cargo to the Armenian army.

Consequently, in view of the concerns of the Azerbaijani side, Georgian leadership repeatedly denied the allegations about taking action against Azerbaijan’s interests, including opening of the railway.

Eldar Zeynalov, a human rights activist: ‘The main problem here is certainly not a technical one. It was, in fact, by means of this railway that the 11th Red Army was able to reach Baku so easily in April 1920. That’s the reason why Georgians do not want to restore it.’

‘As for Azerbaijan, it does not want this to happen because the reconstructed railway will economically strengthen Armenia and, in the event of a war with Azerbaijan, will allow it to redeploy troops, weapons and ammunition from Russia. Light weapons could be delivered by air, whereas armored vehicles and missiles could only be delivered over land.’

Togrul Mashalli, an economist, sees the problem as follows:

‘Railway transport has played a significant role in Azerbaijan’s economy, though it started to decline as early as the 1970s. That was due to the fact that oil from Baku was being supplied more and more by sea or via a pipeline.

The imported raw materials were the products transported via the railway, roughly 28% of items transported.

Imports by rail mainly came from Russia (bauxite, various metals), but passing through Baku-Makhachkala and eventually, Georgia. Another 27% were transits to Central Asia and Armenia (some of which went to Georgia).

Railway exports accounted for 19% of this figure of which oil had the largest share. It was delivered by the Baku-Batumi railway tracks.

A significant portion of the ‘export’ (if that term could be used in Soviet times) was along the Baku-Batumi route, totaling about 70-80%. Engineering products were also exported via Batumi. The rest was transported through Armenian and Georgian railway networks.

Thus, Azerbaijan did not really depend on this route. The Julfa railway station is the only section of the Azerbaijani railway that was part of the Moscow-Sukhumi-Yerevan railway.

Before the Islamic revolution in Iran, i.e. until 1979, there was a Moscow-Tabriz train that passed through Sukhum/i. The Makhachkala-Baku-Julfa railway branch has been in use since the ‘80s. Baku-Mahachkala was the major route of that branch.

Today, the resumption of railway traffic on the route Moscow-Sukhumi-Yerevan may be beneficial for Azerbaijan only in one circumstance-in the case of strengthening economic ties between Russia and Iran. This would compensate for the potential loss of transit through the territory of Georgia.’

Yerevan: Desirable but unrealistic

In Soviet times, a passenger train heading from Yerevan to Moscow was symbolically referred to as ‘Druzhba’ (friendship). The Armenian railway old-timers reminisce about the times when a comfortable train attracted even the residents of neighboring Georgia, who were en route to Moscow. They frequently took this train to travel to the USSR capital and other cities.

From the memoirs of Osto Mkrtchyan, an engineer:

‘People primarily took the Moscow train to travel to the Black Sea on vacation. Sometimes they went on business trips to Moscow or St. Petersburg by train. The ‘Druzhba’ train was exceptional in its comfort and excellent service. A railway trip to Moscow took two days and to Sochi, almost a whole day.

Linens were carefully washed and ironed. Those who travelled to Moscow, had their meals in the train’s dining car, whereas those who travelled to Sochi had to take some food along with them. But the most memorable thing was the tea, served by the passenger car attendant.

One could have as many cups of tea as one desired. In addition, this train’s tea was noteworthy for its taste. The tea they brewed was something special.

A trip to the Black Sea or Moscow also dazzled traingoers with its scenery. Georgia’s beauty was customary for the Armenians, who went to the Black Sea almost every year.

Whereas the Russian landscapes were remembered for their pinery. One could sit for hours and watching the trees, being sped past, from the train car window.’

From Seda Arzumanyan’s memoirs:

‘The trips to Moscow by the ‘Druzhba’ train were special. I still remember the taste of pickles and Molokan cabbage, bought at a station during one of the stops, and I also remember the ruddy elderly women in Russian shawls, who were selling them and graciously inviting their clients to buy something’.

Khoren Avetisyan, an 88-year-old a second or third generation railwayman, recalls his work in the Soviet era with nostalgia. At the peak of prosperity of the Armenian railway, the Yerevan station received over 30 cargo trains, each with 50-60 wagons, in addition to 12 or more pairs of passenger trains.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union so did railway transit dwindle.

‘Today, the number of cargo trains arriving at the station has decreased to two or three, and there is only one direction indicated in the train schedule booklet–Georgia,’ he notes with regret.

It was considered prestigious to work on the railway in the Soviet times. There were many applicants, but Avetisyan, a promising young man, who had just graduated with honors from the Railway Technical School, was appointed a block signalman. Then, in 1972, due to his incredible workmanship, he headed one of the most difficult sections of the Armenian railway, the Yerevan station. It was under his leadership that it was ranked among the Soviet Union’s top three best stations by its organization of inbound and outbound traffic.

Khoren Avetisyan worked as the chief of the station until 1994, but he did not collect pension after finishing; he worked as deputy chief of the station, in charge of operations for ten more years.

After he retired, he set up a museum at the railway station, comprising the entire history of the Armenian Railway. It started in the late 19th century, with the Russian Emperor Nikolay II’s decree on the construction of a railway from Tbilisi to Kars [July 5, 1895].

The first train arrived in the present-day Gyumri, referred to then as Alexandropol, on February 7, 1899. Despite the severe cold, thousands of citizens and military men came to the railway station to get on board.

When telling the history of the origin of the railway, the elderly museum curator regrets that the railway has become decayed nowadays. He believes it is possible to revive the railway service within a day. However, for that purpose it is necessary to get the Abkhaz railway up and running.

As for the Armenian specialists, they also see no prospects for the reestablishment of railway transit with Russia via Abkhazia–with only one ‘but.’

China-Russia international transport corridor

Ara Papian, a political analyst and President of the ‘Modus Vivendi’ Center for Social Science, believes that the Transcaucasian railway will acquire importance provided that it reaches the Persian Gulf, and for that purpose it is necessary to restore railway traffic through Nakhichevan.

In his opinion, the technical problems related to the use of Nakhichevan railway could be resolved, but to overcome political obstacles the superpowers should have their own say.

It’s the interest of Russia, the EU and the USA, that can make the delivery of goods from the Black Sea to the Persian Gulf by the railway through Abkhazia and Nakhichevan a reality.

Ara Papian underlines that it makes sense to discuss only the economic component, and the revitalization of railway transit via Abkhazia and Nakhichevan should in no way be connected to the resolution of Karabakh and Abkhaz conflicts.

‘If it’s all tied into one-then it’s not worth talking about it, since these conflicts will not be resolved for at least another twenty years,’ he says.

The possible restoration of railway transit via the Caucasus without conflict resolution has been widely discussed in Armenia.

To put it short, the plan is as follows:

• The European Union, which has influence on Georgia, insists on opening the railway through Abkhazia.

• Whereas Russia, which has influence on Azerbaijan, wants makes an arrangement and counter its objections.

However, even those who consider this plan as realistic, say that the superpowers will not be interested in revival of railway transit unless Armenia is the final destination.

They say the railway should be planned as an international means of transport from Russia through the Caucasus to Iran and afterwards to China, with access to the Persian Gulf.

Vahagn Khachatryan, an economist, is less optimistic. In his opinion, it is first necessary to take into account the interests of Georgia, which will be able to accept the loss of Abkhazia. Second, it will be necessary to settle Armenia-Iran railway communication issue.

Will the railway pass through Nakhichevan, as it had before the Karabakh conflict, or will a new railroad be laid? The second option seems a little bit fantasque due to the complex mountainous terrain of the southern part of Armenia.

Russia: It doesn’t have time for the Caucasus’s ambitions

In Soviet times, the Transcaucasian railway performed a number of important tasks: it linked Armenia, Georgia and Azerbaijan to the rest of the country. It served as the major route for transportation of Baku oil. It was an important military supply line, meeting the requirements of the Transcaucasian Military District, which was at close quarters to the NATO southern flank.

But this railway had another function that was never officially recorded. It was actively used by those who were referred to in the USSR as the shadow economical operators (‘black-marketeers’ and ‘underground workshop owners’).

Sergey Georgiev, a resident of Moscow, recalls:

‘Getting a job as a passenger car attendant on the Moscow-Tbilisi or Moscow-Yerevan train was the dearest wish of any go-ahead man in those times. The bribe for that position amounted to 500 RUB, quite a huge sum, one that was earned back easily.

While on other routes the attendants received their income mainly from ‘stowaways’–fare dodgers, here the main source of income were products. There would be a seasonal product, for example, the first tomatoes and greens in spring and the Abkhazian tangerines and nuts from Georgia, in autumn. Moscow markets were the main sales outlets.

The general-purpose, off-season goods-jeans from Poland and India and some other things were transported in the opposite direction. Audio cassettes with Turkish pop music records were in high demand in Baku. Those passenger car attendants, who were so inclined, risked transporting “hash (marijuana) from the Transcaucasus to the capital.

All this commodity turnover was not a secret to anyone-everybody knew, how much and which of the police and OBKhSS (Department Against the Misappropriation of Socialist Property) officers should be paid to at each railway station.

In the late 80’s and 90’s, I discovered a lot of familiar names (of those officers) in the news-they were raised to great career heights.’

In the post-Soviet period, the restoration of rail transit with the South Caucasus was last actively discussed in the Russian media before the Sochi Olympics. Since then, interest in it has been lost and lobbyists for this could not be found.

There is a simple explanation for that.

Russia’s present-day foreign policy does not provide for large budget allocations for the development of this project, and, consequently, the major stakeholders, such as the Russian Railways or Gazprom, are not interested in this issue.

The rapid deterioration of the economic indices, the devastating state of the public sector, the fast-growing social tension, the extremely shaky situation in the North Caucasus-all this make the Russian authorities minimize their activity in the regions, where its crucial interests are not being threatened right now.

The South Caucasus is one of those regions.

This does not mean that at some point the South Caucasus issue (and the related railway transit issue) won’t all of a sudden become relevant-the Russian authorities have constantly demonstrated an extraordinary eccentricity in its foreign policy in recent years.

However, under the present circumstances, it can only be a short-term propagandist effort, aimed at solving some domestic political questions which surface.

Summary

In the opinion of Alexander Iskandaryan, a political analyst and Director of the Caucasus Institute, a railway line through the Caucasus is the mere fantasy of journalists since: a) there are too many obstacles on the path towards the implementation of this project; b) there is a rapidly developing new transportation network in the region, which eliminates any need for reviving an old one.

Much has been said above about the different types of obstacles and needs no reiteration.

As for the new transportation network:

• Georgia, which has no diplomatic relations with Russia, has not closed the road from Vladikavkaz that passes through the Upper Lars (keeping Armenia in mind, for which it now represents ‘a lifeline route’).

• The construction of the Kars-Akhalkalaki railway is almost completed.

• The ‘North-South’ highway-a road linking the Persian Gulf with the Black Sea, is being constructed in Armenia. Some of its sections have already been put into operation. It is expected that this route will become more active after the lifting of sanctions against Iran and its accounts become unblocked.

In short, Moscow-Sukhum /i and Tbilisi-Yerevan trains really seems to be an illusory prospect. However, quite pragmatic conclusions can be made:

While implementing international megaprojects the problem of investment could be solved quite easily and quickly. If a long-lasting peace is established in the region, and if there is the superpowers’ will it so, all three countries of the South Caucasus can become the key stakeholders in a number of large-scale international projects.

Toponyms, terminology, views and opinions expressed by the author are theirs alone and do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of JAMnews or any employees thereof. JAMnews reserves the right to delete comments it considers to be offensive, inflammatory, threatening or otherwise unacceptable