Why are Armenian women marrying foreigners more often? Stories of three families

Mixed marriages in Armenia

Residents of Armenia have the impression that the number of mixed marriages has recently increased. This may be due to the influx of a large number of Russians since the spring of 2022, after the outbreak of war in Ukraine. However, there are no statistics to support this assumption.

The Statistical Committee does not yet provide data for 2022. In 2021, 17,165 marriages are registered in Armenia, of which only 135 are mixed marriages. In 2020, 12,179 marriages are registered, and only 97 of them are with foreigners.

These numbers were even slightly higher in the previous two years. In 2019, 520 marriages with foreigners were registered (out of 15,561), and in 2018, 495 (out of 14,822).

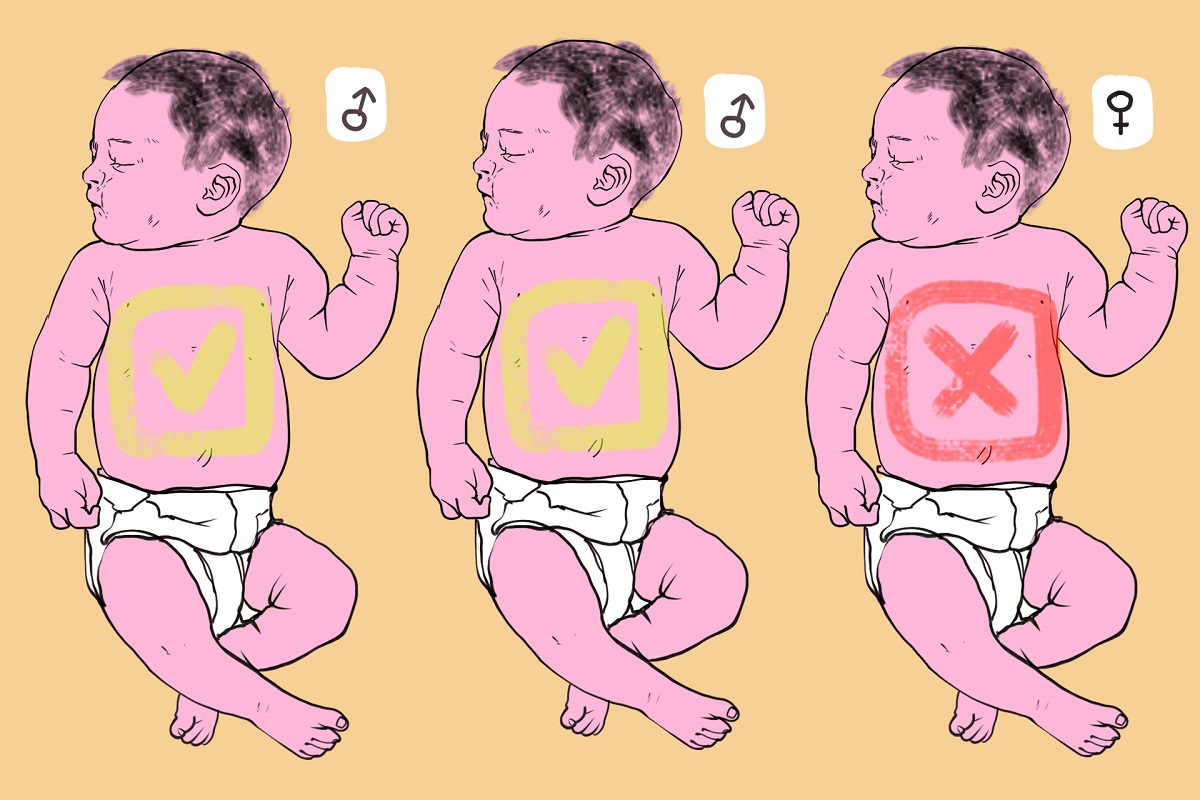

Interestingly, marriages between Armenian women and foreign men dominated the statistics in all years.

They accounted for 56 per cent of mixed marriages in 2021, 63 per cent in 2020, 55 per cent in 2019 and 52 per cent in 2018.

- How to keep labor migrants in Armenia? New EU proposal

- Construction boom in Yerevan, prohibitively high housing prices will remain for the time being

- Attempts to preserve the tourism business on the border between Armenia and Azerbaijan

Women tell psychologists about the reasons

“Young girls and unmarried women often say that it is difficult to find a suitable man to marry in Armenia today. Men, by the way, also complain that it is difficult for them to find a suitable soul mate. And this is not the opinion of one or two people, it is a widespread point of view. And people think that if they can’t find a suitable person in Armenia, they can find one abroad,” says psychologist Mirdat Madatyan and emphasises that creating a strong family with a foreigner is a more complicated process, which is not for everyone:

“In case of mixed marriages, there are much more contradictions and differences in the couple. They are conditioned by language, religious peculiarities, traditions. When a person takes this step, he should be ready to face these difficulties. And over time he should form his own family traditions – linguistic, religious, which will be acceptable to both”.

The psychologist emphasizes that many mixed marriages were created in Soviet Armenia as well. He believes that even now the majority of Armenian society has a favorable attitude towards mixed marriages.

“Armenian and Indian family models are practically the same”

Pankaj Singh from India does not share the psychologist’s view of the positive attitude towards mixed marriages in Armenian society. He agreed to the interview on the condition that the conversation would take place only with him and without a camera. He explained his position by a previous negative experience:

“Once we had a TV interview with our whole family. When I saw the aggressive comments that appeared under the video, I was very upset. They showed how little tolerance people have. From that day on, I decided that I will never allow my family to be shown on video again. I have to protect her. I don’t want people’s aggression to affect my children’s quality of life.”

Pankaj Singh first came to Armenia in 2003, when he was 18. He received his medical education in Armenia and returned to his home country. However, after a few years he returned to Armenia to specialize.

In parallel with his studies he worked in several medical centres, where he met Ani, his future wife, a nurse.

Pankaj Singh’s parents took a favorable view of their son’s desire to marry a foreign woman. But there was tension in the girl’s family initially.

“Ani’s family accepted me well as a person, but they had issues with me. Several times I went to their house literally for interviews. Her family talked to me the way they do job interviews.

The issue that bothered them the most was the question of religion. They said to me, “You’re not a Christian, you’re of a different religion. If you have children, what religion will they adopt?” I said I had no intention of forcing my child to be a Christian or a follower of Hinduism. They will grow up and decide for themselves, but I will accept whatever they decide.”

Eventually the family agreed and the couple got married.

“Since I am not a Christian, we could not get married in a church. One day I told Ani: we have a few days off work coming up, let’s get married. We gathered 10-15 people, had fun, and that was it.”

Later, the couple had a lavish wedding ceremony in India according to local traditions.

Pankaj Singh emphasizes that despite religious, cultural and other peculiarities, Armenians and Indians have the same attitude towards family matters.

“It was very important for me to have a strong family. Studying the family models of the two nations, I realised that the Armenian and Indian family models are almost identical. That’s why it’s not difficult for both of us to live in this model.

And the peculiarities of the peoples complement each other. For example, in India they cook spicier food, and I like it. When Ani started living with me and trying different Indian dishes, she liked it. And now she cooks like that too,” he says.

“There are different threads that bind me to Armenia. This country gave me an education, gave me a family. I built my home here. And I am indebted to this country. I do everything to be useful to Armenia. If life happens so that I go somewhere else, I will definitely come back,” he assures.

“Choices must be made solely by the dictates of the mind and heart.”

German Ricardo Bergman and Louise Naslian met for the first time in 2016 in Yerevan, during the European Heritage Days event. They remembered this fleeting encounter years later, looking at each other’s photos when fate brought them together again.

After a year of volunteer work in Armenia, Ricardo returned home. But after a few years he decided to return, this time permanently. He settled in Dilijan. In 2021, Ricardo met Luisa again by chance in Yerevan. She was planning to open an art studio in Dilijan. At first, this became a common theme for them.

After a while, Ricardo asked her mother for Luisa’s hand in marriage. She agreed, expecting a traditional Armenian wedding. Instead, the couple soon announced their decision to start a life together.

“My mum woke up one morning and saw me packing my things, as Ricardo and I would be living together, having rented a flat. It was a shock for her, but I left because it was normal for me. I know couples who broke up a year after a lavish wedding. So the wedding didn’t matter to me. Ricardo didn’t have a stable job at that time, he couldn’t take on such expenses,” says Luisa.

Nevertheless, her relatives warmly welcomed the groom. Luisa thinks this was due to Ricardo’s charisma and the fact that the family had already accepted another foreign son-in-law before him.

“My sister’s husband is Ukrainian. One day my aunt said: “What imported sons-in-law we have.” There were no other conversations about foreign sons-in-law,” says Luisa.

Ricardo was always treated well in the community too. Luisa surmises that this is due to language skills. Her husband speaks Armenian perfectly – and immediately became “one of our own” to everyone.

“Our couple has never been criticized, not even slanted glances. But I know mixed families who are regularly criticized,” says Luiza.

She has her own opinion on why Armenian women have been marrying foreigners more often in recent years:

“In many Armenian families, girls are oppressed and boys are privileged. As a result, boys do not learn anything, their mothers do everything for them. And girls are the opposite: they do household chores, study and work. Being abroad within the framework of various programmes, they acquire a broader outlook and become more self-confident.”

Her husband’s German poise and equanimity and her Armenian emotionality have had a positive effect on both of them, Luisa notes:

“I am a very warm person by nature, and now Ricardo has changed, he has become more sociable, more cordial to people. And thanks to him, I have become even more tolerant, more balanced and calm.”

The spouses came to a common denominator on issues of faith and religious values.

“Ricardo doesn’t particularly believe in God, but he goes to church with me,” Luisa says.

“I don’t think religion is important. If you want to do something good, you can do it without religion. There are many people who say they are Christians, but they don’t act according to their conscience, they lie,” Ricardo explains.

Luisa, who has two years of a harmonious relationship with her husband under her belt, advises girls who are faced with the choice of whether to marry a foreigner:

“If you consider any element of public opinion in your choice, you are being dishonest with yourself. Your choice should be based solely on the dictates of your mind and heart”.

“Meeting Len was a God-given blessing for me.”

Australian Len Wicks and Armineh Hakobyan got married 12 years ago. For many years they lived abroad, but in 2018 they bought a plot of land in the south of Armenia, in the village of Areni and moved permanently.

“It was never a matter of principle for me that I should marry an Armenian. I always thought the main thing was that he should be a good person. The only contradiction we had to overcome, perhaps, was the difference in attitude towards the problems that arose.

We Armenians prefer not to talk about them, we think it is better to keep silent at that moment and the problem will solve itself. Len doesn’t think so. He thinks it is necessary to talk about the problem in order to find a solution. Over time, I realised that silence is not the answer. If there is a problem, you should talk about it,” says Armine.

She lives with her foreign mother-in-law. She says there is a surprising and pleasant feature in her relationship with her husband’s mother:

“It manifests itself in female solidarity. Mothers-in-law in Armenia mostly protect the interests of their sons, try to do everything to make them feel good. And my mother-in-law tries to support and protect me more. She says to me, “Make it good for you, not only for my son”.

As for her foreign husband, she says everyone around her has always treated him very well:

“And my mum was just fascinated by him. When I first met Len, she told me it was a Cinderella story. I’ve been through a lot of difficulties and meeting Len was a God blessing for me.”

Meanwhile, her husband’s friends were ambivalent about Armine marrying Len, a sought-after and highly paid professional.

“There are women who marry foreigners for the sake of obtaining citizenship or for money. In those years, this often happened. Some of Len’s acquaintances thought I had chosen him that way too. But marriages like that can’t last long. When they saw our relationship and got to know me better, over time they realised that they were wrong,” says Armine.

“The type of Armenian woman became a discovery for me, thanks to Armineh. I started to study the history of Armenia and found out for myself that the Armenian woman is a force that connects the society, its different layers. And I wonder why the role of Armenian women in Armenia is underestimated.”

Armineh conveyed to her foreign husband her love for Armenia. Inspired by this sentiment, Len published a book, “Origins: a Discovery.” He now runs a blog and speaks weekly to English-speaking audiences on the programme “Straight Talk from the Motherland”. He talks about the most important news and issues in Armenia.

“There are many mixed families who stick to traditions, are bearers of Armenian values and patriots. We also try to be like that and be useful to our country,” says Armineh.

Len, who has extensive experience working with the governments of various countries, has even expressed his willingness to cooperate with the leadership of Armenia and the unrecognized NKR. However, he has not yet received a response.

Follow us – Twitter | Facebook | Instagram

Mixed marriages in Armenia