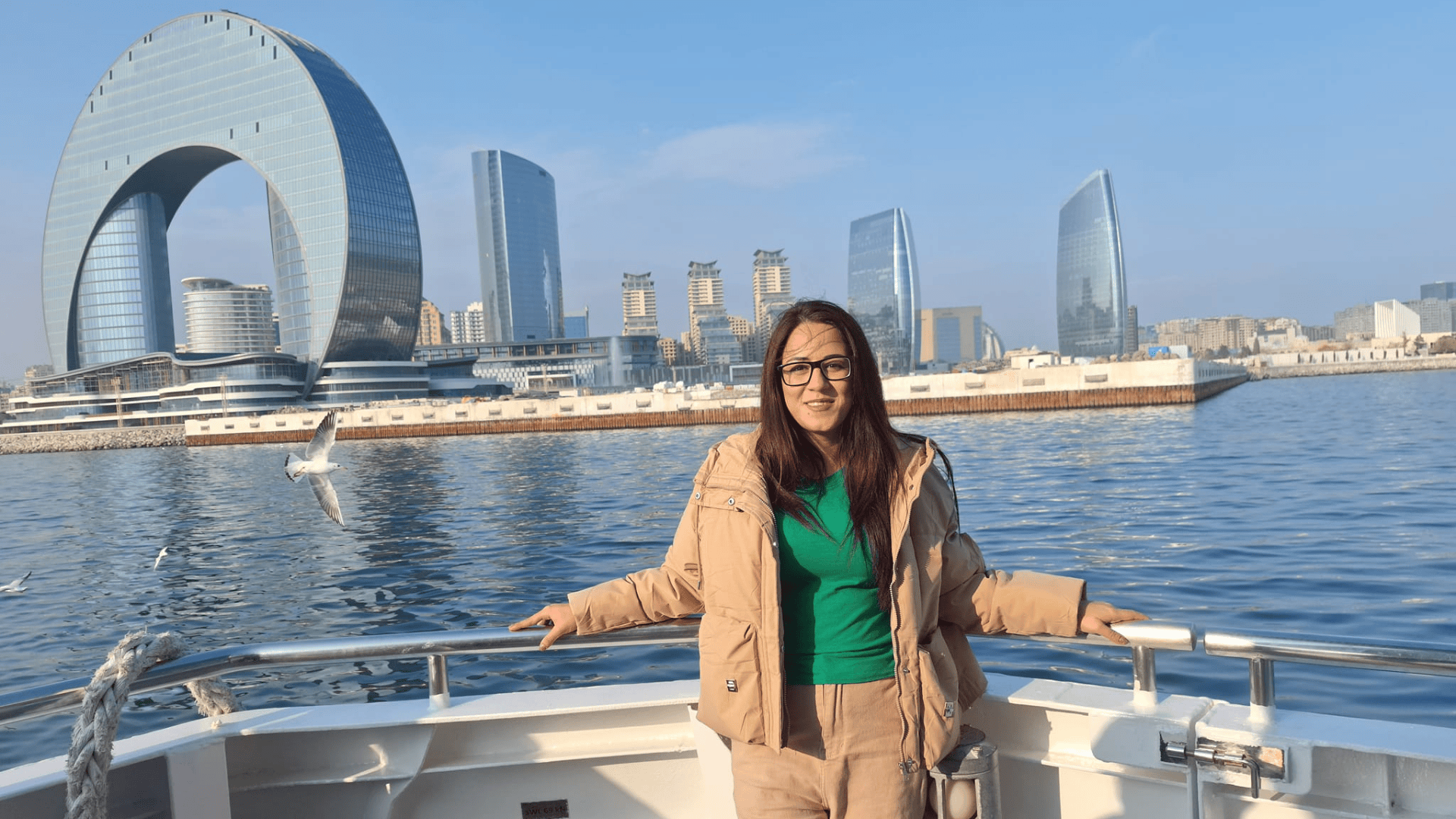

Imprisoned journalist: "You have to feel as if you’ve always been here"

Azerbaijani journalist writes from prison

Journalist Ulviya Ali, who has been in custody in Azerbaijan since May 2025, has sent a letter describing “a week in the life of a political prisoner.” She writes about her days in the Baku detention centre, the process of adapting to prison conditions, her daily routine and her feelings.

On the night of 7 May, Baku police violently detained journalist Ulviya Ali (Guliyeva) as part of the “Meydan TV case” and searched her home. That same day, the Khatai District Court ordered her to be held in custody for one month and 29 days, a term that was later extended several times.

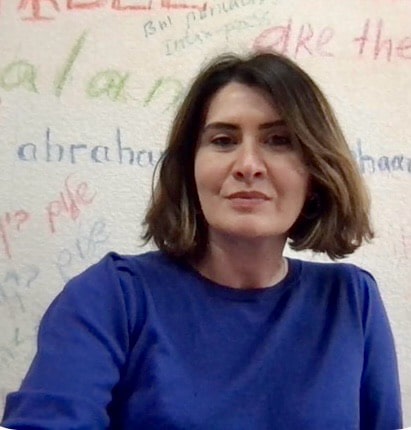

On 6 December 2024, several Meydan TV colleagues were arrested: editor-in-chief Aynur Elgunesh (Gambarova), reporters Aytaj Tapdyg (Ahmadova), Khayala Aghayeva, Aysel Umudova, Natig Javadli, and freelance journalist Ramin Jabrayilzade (Ramin Deko). They were later joined in detention by journalists Shamshad Aghayev, Nurlan Libre (Gahramanli), and Fatima Movlamli.

All were charged under article 206.3.2 of the Criminal Code — smuggling committed in a group by prior agreement. Meydan TV maintains that the arrests are linked to their journalistic work and aimed at silencing independent reporting.

We publish the full text of the journalist’s letter

One of the things everyone wonders about is how we spend our time in prison. Of course, since I’m in isolation, I can’t speak for others, but I’ll try to describe what one week looks like for me.

When I was free, I was so busy that I could never get my sleeping schedule in order and often went to bed very late. Just four days into my detention, I was already “reformed” — waking up between 9 and 10 in the morning. To be honest, it doesn’t always happen by choice.

If someone asked me what I dislike most about prison, without hesitation I’d say being woken up by someone else. But more on that later.

In prison, there are inmates known as khoz (from the Russian khozyaystvo, meaning “housekeeping”). These prisoners are paid by the state to do maintenance work. Unlike the rest of us, who cannot leave our cells, the khoz inmates can move freely inside the prison. They are easy to recognise — they wear fluorescent green jackets over their clothes. They spend their time in custody working, and their wages are sent to their families. They become, in a sense, our hands and feet: stocking and retrieving food from the fridge, buying things from the prison shop, taking care of repairs and other daily needs. Every morning, around 6am, they deliver two boiled eggs and one loaf of bread to each prisoner.

Now to the difficult part: just before 10am, female guards open the cells one by one to check if everyone is “safe and sound.” Some of them have such piercing voices that it’s impossible not to wake up, even in the middle of the best sleep. After that, I rarely manage to fall back asleep. To be honest, I was the same at home — that’s why I used to keep my phone on silent at night so no one would disturb me. Sadly, here there’s no “silent mode” for people.

The second thing I dislike is the lack of personal space.

There are usually two or three of us in the cell. Sometimes you just need to be alone, but that’s impossible. Still, having good cellmates counts as the greatest stroke of luck in here.

Once I’ve been jolted awake, I toss and turn for a while before realising I can’t fall back asleep. Then I wash my face and hands. After that, I leave the previous day’s rubbish by the cell door for the khoz inmates to collect and take to the main bins. I’ve taken on the role of handling food in our cell, so I start preparing breakfast. I try to make the menu varied, to add a little colour to the monotony of prison life.

When I was free, I used to cook meals for some of our political prisoner friends. One inmate I didn’t know told me: “I know you — you used to cook for the prisoners.” Since I love it when my food is praised, it warmed my heart that even here, my cooking had become known.

After breakfast we tidy the cell. It’s not hard to clean, since it measures just 12 steps long and 8 steps wide. We’ve also divided the chores between us. What I like most is that a sense of communal life still survives here.

Sharing is one of prison’s few redeeming features.

It saddens me deeply to see the “forgotten” prisoners. Some never get visits or food parcels, either because their families can’t afford it or have abandoned them altogether. The prison authorities do provide the standard meal, known as balanda, but I’ve never tried it. I imagine nothing can replace food from home, whose quality you trust. That’s why sharing becomes essential — you can’t eat your fill while the person next to you is hungry.

From home I only accept raw food, so I can cook myself. It fills the time and keeps me occupied.

If anyone asked how I pass my sentence, I could answer: by cooking.

I’m allowed two phone calls a week. After tidying up, I usually make one. But I don’t enjoy it much. With only 15 minutes, and for obvious reasons, I have to watch what I say. Things can be misunderstood, half-heard, or taken the wrong way — and that only adds stress.

The biggest help in passing the time is the television.

I hadn’t watched TV in ten years at home, and now relying on it feels almost ironic. I usually watch music channels. The main entertainment for prisoners, though, are Turkish soap operas, Russian films and talk shows. You’re also forced to endure Azerbaijani channels because of your cellmates — which feels like torture. Sadly, most shows, singers and presenters are mired in mediocrity.

The exception — my salvation, really — are the intellectual programmes on İctimai TV. Sometimes Mədəniyyət TV also airs something worthwhile. With the music channels on in the background, I start thinking about what to cook for lunch.

In remand prisons, there’s only a small “walking room,” and just one hour a day in it. There isn’t much chance to move, so I try to make sure I also prepare proper soups twice a week. Today, for example, the menu includes tomato soup.

Sometimes my cellmate doesn’t want to go to the walking room, so I use the chance to be alone and read. Since I read aloud, solitude feels more comfortable. At the moment, I’m reading a book about my favourite painter, Caravaggio.

By the way, for those who don’t know: besides journalism, I also paint. I try to create something here as well.

People say art knows no borders. But for now, the barbed wire keeps my muses away.

So I don’t draw much — all I see from the window are walls and wire, and even the sky is framed by iron bars.

One of the things I dislike most in prison is waiting. And I’m not a very patient person. Most of my time is spent waiting — for visiting day, for my lawyer to come. Most of all, because communication is so restricted, you can’t just pick up the phone as you would outside and ask, “Are you on your way?”

Speaking of waiting, here even hot water has its own order and schedule. On Wednesdays and Fridays we get it for an hour and a half. That time is for bathing and doing laundry. When there’s no hot water, we use a heater. Cold water, too, comes on a timetable. It flows from 7am to 3pm, then again from 6pm until 11pm. For the rest of the time we collect and store it in containers. So, in a way, most of the day goes by, leaving little room for boredom.

I try not to lose my sense of reality in the prison’s information blockade.

When I was free, I often noticed that our friends who were political prisoners started losing that sense after a while. Sometimes they would name the exact day they expected to be released. We outside would laugh, but we also felt sad, because we had a clearer view of the situation. Maybe it wasn’t about losing touch with reality — maybe it was just hope, one of the few things that keeps people going. That’s why I asked Afiaddin Mammadov, who has been in prison for nearly two years, for some advice. One of his tips was not to think about freedom. He said dwelling on the outside world only suffocates you. You have to feel as if you’ve always been here. I’ve focused on that advice and try to follow it.

Even months before my arrest, I made a list of “things to do in freedom,” so I wouldn’t have any regrets. I managed to tick off almost all of them.

On the day of my arrest, less than two hours after arriving at the Baku detention centre, I suddenly thought — as if I had no other worries — that I was going to prison this year without eating plums. And then I forgot to add them to the list of food parcels. A few days later my mother brought a package. She seemed to sense what I wanted and put plums in it.

I’ve hung a photo of my cats above my bed. Sometimes I spend time just looking at them, hoping they’ll live long enough to wait for me.

The most thrilling part of prison is waiting for lawyers. It’s exciting not only because you never know exactly when they will arrive, but also because they are often your only real link to freedom.

For me the most exciting day is Friday, because Saturday is visiting day and I spend more time preparing for it. I tidy myself up, paint my nails and go through my usual little rituals. On Saturday I meet my mother. Each time, I pick a flower in the prison yard to bring her as a thank-you. I once joked to her: it’s a good thing I was arrested, otherwise you wouldn’t be seeing me so often. When I was free, I was too busy to visit her regularly. After about an hour together, we say goodbye and I return to my cell.

Saturday after the visit follows the same routine: tidying up, cooking, watching TV. Within an hour the food parcels brought by family arrive, and I spend time checking the list and putting everything in its place. Anything that goes into the fridge has to be marked with the cell number so it doesn’t get mixed up. I’ve adapted so quickly that it feels as if I’ve been labelling food all my life.

One of the things that occupies us during the week is making a list of needs. We draw up what’s missing and divide the tasks among ourselves so we know what to ask for in the next parcel.

The dullest day for me is Sunday, because it’s neither a phone day, nor a visiting day, nor a lawyer day.

I usually spend it sleeping, giving myself a rest.

In my last months of freedom, the song I listened to most was “Proshchalsya” (“Saying Goodbye”) by the Russian rock band DDT. It’s about those forced to leave Russia because of the war in Ukraine, saying farewell to every corner of their homeland. Walking down the street or sitting in a café, I felt as though I too was saying goodbye to my last days of freedom with that song in my ears. Even here, I still hear “Saying Goodbye” playing as I try to fall asleep…

Saying farewell to my homeland,

buried under the zinc coffins of war —

saying farewell to my homeland

took so long that we’re still together.

Ulviya Ali

Baku Detention Centre