Azerbaijan: selective punishment for financial violations - what “culture of corruption” looks like. Opinion

Corruption reports in Azerbaijan

The Audit Chamber of Azerbaijan’s report for the first six months of 2025 shows that structural problems in the use of public funds remain relevant.

As a result of audit inspections, financial violations totaling 65 million manats (about $38.3 million) were identified. It was stated that direct damage to the budget amounted to 17.8 million manats (about $10.5 million).

These figures once again confirm the weakness of financial discipline in the country. However, the most notable issue is neither the scale of the violations nor their nature.

The main question is this: why, despite such obvious cases of abuse and corruption, is responsibility borne only by “selected individuals”?

This topic is not limited to the current reporting year. It has long become a symbol of a recurring structural problem year after year.

From corruption scandals involving the presidential family to embezzlement by heads of executive authorities — those involved in these local and international corruption cases mostly remain unpunished.

Those who are punished often find themselves free again soon after.

Audit Chamber reports: figures, structures, and lack of consequences

The 2024 annual report by the Chamber of Accounts of the Republic of Azerbaijan revealed widespread misuse of public funds. According to the report, which was discussed in a parliamentary committee, more than 80% of the 42 audits carried out uncovered violations of budget legislation and other legal provisions.

Particularly serious breaches were found in the area of public procurement. The Chamber’s conclusion states that 57% of all public purchases in 2024 were made without tenders, through direct contracts — a major violation of transparency principles. In total, financial irregularities worth nearly 575 million manats (approx. $340 million) were identified, of which around 113 million manats (approx. $66.5 million) were classified as direct damage to the state budget.

These findings point to deep-rooted problems in how public funds are allocated and spent. According to the Chamber, in several cases, funds were used for purposes unrelated to their original intent, including excessive spending on transport, gifts, and international events. Violations also included the failure to publish procurement plans and delays in fulfilling contracts.

A similar pattern emerges in the Chamber’s latest semi-annual report, released in July 2025. According to the data, in the first six months of 2025, violations totaling 65 million manats were uncovered, with 17.8 million manats in direct losses to the state budget. Again, there were instances of misallocated funds, inflated spending on transport services, gifts, and international travel, as well as procurement irregularities.

The semi-annual report does not name the institutions responsible for these violations.

It only states that irregularities were found across various government bodies.

Institutions

According to the Chamber of Accounts’ 2023 report, evidence of violations uncovered at several state institutions was handed over to the General Prosecutor’s Office. These institutions included the Sumgayit Medical Centre (under the Administration of the Regional Medical Divisions, TƏBİB), Nakhchivan State University (Ministry of Education), the Ministry of Youth and Sports, the now-dissolved Baku Transport Agency, the Cultural Heritage Protection Service, the Film Agency, Ganja City Hospital (also under TƏBİB), and the state broadcaster AzTV.

In addition, documents related to violations in urban planning and architecture in the Nakhchivan Autonomous Republic were forwarded to the State Security Service. Overall, the head of the Chamber noted that in 2024, materials from eight oversight investigations were submitted to law enforcement bodies, and the Chamber supported steps toward stronger legal action.

As a result, some investigations were launched. For instance, based on audit materials from the Chamber covering 2020–2023 at the Azerbaijan National Academy of Sciences, the General Prosecutor’s Office’s Anti-Corruption Directorate opened a criminal case into large-scale embezzlement and abuse of office.

Lack of consequences

Despite the findings, high-ranking officials are rarely held accountable for such violations. The leadership of the Chamber does not disclose the names of those responsible, and in most cases, the materials are simply forwarded to the Prosecutor’s Office for legal procedures. In other words, the violation is acknowledged — but no one is named.

So far, there is no public information indicating that any minister or senior official has been dismissed or prosecuted as a result of the Chamber’s findings. It is only known that certain cases, such as the one involving the National Academy of Sciences, are under investigation.

A climate of impunity: Legal gaps and selective political will

On paper, Azerbaijan has mechanisms in place to fight corruption. In practice, however, their enforcement remains selective and ineffective. The Anti-Corruption Directorate under the General Prosecutor and other agencies tend to focus on lower-level officials, while senior figures often remain untouched.

Since 2020, the heads of local executive authorities in districts such as Neftchala, Imishli, Bilasuvar, and Shamkir have been arrested on corruption charges. Yet many of them later made headlines for receiving reduced sentences or being released early. Meanwhile, although a criminal case was opened following the audit of the National Academy of Sciences, the process has not led to any meaningful public consequences.

Legal gaps

In Azerbaijan, criminal cases for bribery and embezzlement have been brought against officials at various levels. Anti-corruption operations targeting regional executive heads have received the most public attention.

Since 2020, the State Security Service has carried out special operations across a number of regional administrations. As a result, the heads of executive authorities in Neftchala, Bilasuvar, Imishli, Jalilabad, Aghstafa, Yevlakh, Kurdamir, and Shamkir were arrested. Most were prosecuted for bribery, embezzlement of public funds, and abuse of office. For example:

- Vilyam Hajiyev, former head of Imishli district, was arrested in May 2020 and sentenced to 12 years in prison (reduced on appeal to 8 years and 6 months). Investigators presented evidence of bribery and abuse of power.

- Mahir Guliyev, former head of Bilasuvar, was sentenced to 11 years for bribery (later reduced to 8 years and 3 months).

- Ismayil Valiyev, former head of Neftchala, was detained by the State Security Service in 2020 and sentenced to 10 years (reduced to 6 years and 2 months by the Supreme Court in 2024). Investigators found he and his team issued permits in exchange for bribes and embezzled budget funds.

- Alimpasha Mammadov, former head of Shamkir, was arrested in 2021 and sentenced to 11 years and 6 months for abuse of office, embezzlement, bribery, and money laundering (later reduced to 10 years and 6 months). His case included allegations of looting the district budget and awarding state contracts to relatives.

- Nizameddin Guliyev, former head of Aghstafa, was sentenced to 9 years in prison in 2020 but died in custody in 2021 due to COVID-19.

- Goja Samadov, former head of Yevlakh, was sentenced to 7 years and 3 months for corruption. His sentence was later eased, and he was conditionally released in 2023.

- Jeyhun Jafarov, former head of Kurdamir, was sentenced to 8 years and 6 months for bribery in 2020. After appeals, the term was reduced to 4 years and 6 months, and he was released in early 2025.

These are only a few examples. In total, over the past few years, more than 10 regional executive heads and senior local officials have been prosecuted for corruption-related offences.

Some former ministers have also come under scrutiny. For example, Salim Muslumov, former Minister of Labour and Social Protection of the Population, was arrested in 2021 on charges of accepting large bribes while in office. Investigators claim he established a systematic bribery scheme within the ministry in exchange for awarding tenders. He is currently under house arrest, awaiting the outcome of his trial.

Earlier, in 2015, a major corruption scandal broke out at the Ministry of Communications and High Technologies. Several deputy ministers and department heads were arrested, and the minister at the time, Ali Abbasov, was dismissed from his post — though he was not arrested himself.

In 2013–2014, a large-scale extortion scheme was uncovered at the now-defunct Ministry of National Security, where a group of generals allegedly extorted millions from business owners. Several senior officials, including a deputy minister, were arrested as part of the investigation.

Findings from international investigations

Leaks such as the Panama Papers (2016) and the Paradise Papers (2017) also included information linked to Azerbaijan. The Panama Papers revealed that President Ilham Aliyev’s daughters, Leyla and Arzu Aliyeva, held shares in Azerbaijan’s telecommunications sector through offshore companies.

Investigations into former investors in the mobile operator Azercell found that the Aliyeva sisters indirectly owned stakes in the company. The Paradise Papers leak also included data suggesting that the son of Deputy Prime Minister Yagub Eyyubov owns companies abroad. These claims were neither denied nor officially commented on by the Azerbaijani government.

Following the exposure of the Azerbaijan Laundromat scheme, several legal investigations were launched in Europe. In Italy, it was confirmed that former PACE member Luca Volontè had received bribes from Azerbaijan, and in 2021 he was convicted of corruption. In Germany, former Bundestag MP Eduard Lintner was found guilty of accepting large bribes from Azerbaijani sources and received a suspended sentence in 2024. Transparency International described the ruling as a “landmark court decision” in the Azerbaijan Laundromat case.

It also emerged that funds from the scheme were used to boost Azerbaijan’s image in international organizations such as UNESCO.

These events revealed how Azerbaijan’s ruling elite sought to advance their interests abroad through corruption.

Money from the Laundromat also financed luxury purchases, real estate acquisitions in Europe, and personal enrichment by businessmen close to the government.

The so-called Azerbaijan Laundromat was an extensive money-laundering and bribery scheme uncovered in 2017 by the Organized Crime and Corruption Reporting Project (OCCRP). The investigation showed that between 2012 and 2014, individuals close to Azerbaijan’s leadership created a secret fund worth $2.9 billion to expand influence in Europe and launder money.

Using four British offshore companies, the network moved more than €2.5 billion over two years through hundreds of transactions, funding a range of undisclosed purposes.

The Azerbaijani government has never explained how the Aliyev family came to own such vast property through offshore networks. The president’s family declined to comment on the allegations. The Pandora Papers later provided further evidence that the ruling family had amassed vast overseas assets, legalised through hidden financial structures.

These revelations have made the immense wealth of the Aliyev family plainly visible — wealth long criticised by both domestic and international watchdogs. British media even reported that the UK Crown Estate had purchased a £90 million London building from the Aliyev family.

A total of 17 properties were linked to anonymous offshore companies connected to the family.

One of the most striking findings was that Heydar Aliyev, the president’s son, was listed as the owner of four prime properties in London’s Mayfair district — while still only 11 years old. For instance, a building valued at $44.7 million, initially bought in 2009 in the name of a family friend, was transferred to young Heydar just a month later.

Selective political will

All of these developments highlight the selective nature of anti-corruption efforts within Azerbaijan. Law enforcement agencies typically target officials with little political clout or those who have lost influence.

Meanwhile, corrupt activities involving members of the country’s highest leadership remain untouched by the legal system. For instance, despite revelations in the Pandora Papers — including the Aliyev family’s purchase of luxury London property and the transfer of billions through the Laundromat — not a single criminal case has been opened in Azerbaijan.

There has been no official response to such international investigations. In its 2024 Corruption Perceptions Index report, Transparency International noted that high-level corruption in Azerbaijan remains unpunished, and anti-corruption efforts are ineffective due to the immunity of the political elite.

Indeed, although President Ilham Aliyev has named the fight against corruption a priority since taking office in 2003, his family and close associates are frequently cited in international reports as being at the very top of Azerbaijan’s corruption pyramid.

Crackdown on independent media and the collapse of public oversight

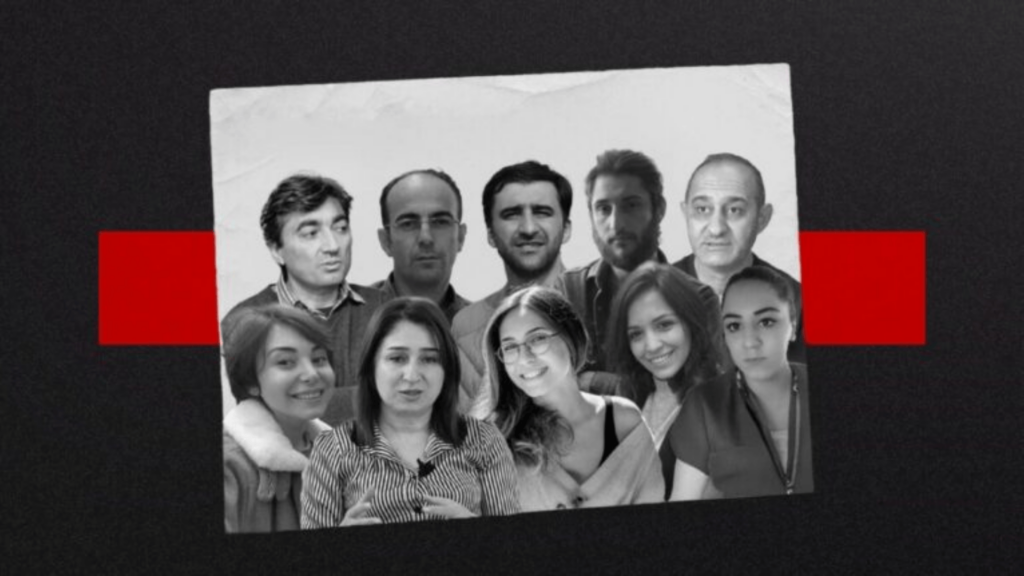

Since late 2023, pressure on government critics and independent media in Azerbaijan has intensified sharply. Independent outlets such as AbzasMedia and Meydan TV, known for their anti-corruption investigations, have faced sustained and systematic persecution. They are routinely denied state registration without justification, their offices are raided by police, and staff are arrested on fabricated charges. The personal bank accounts of journalists — as well as those of their family members — have also been frozen.

Among those targeted were Ulvi Hasanli, director of AbzasMedia, editor-in-chief Sevinj Vagifgizi, and reporters Hafiz Babaly, Nargiz Absalamova, Elnara Gasimova, as well as deputy director Mahammad Kekalov and economist Farid Mehralizade. They were charged with currency smuggling, tax evasion, money laundering, and document forgery — and sentenced to prison terms ranging from 7.5 to 9 years.

Amnesty International has stated that the charges brought against the journalists are baseless and that not a single piece of credible evidence was presented during the trial. Detained media workers face harsh prison conditions and health problems, with reports of being denied necessary medical care. Some have also reported physical abuse and threats.

In December 2024, on a single day, several journalists linked to Meydan TV were also detained — Aynur Ganbarova, Aytaj Ahmadova, Khayala Aghayeva, Natig Javadli, Ramin Jabrayilzade, and Aysel Umudova — along with Ulvi Tahirov, deputy director of the Baku School of Journalism. All were placed in pre-trial detention. The investigation remains ongoing.

Although all of these arrests have been formally presented as economic crimes — such as smuggling and tax evasion — both the public and international organizations believe they are politically motivated, aimed at silencing independent voices that criticize the government and expose corruption.

Retreat of international organizations

Through legislative changes and administrative measures adopted in 2014–2015, the Azerbaijani authorities effectively shut down the operations of many international NGOs or imposed severe restrictions on them. Anti-corruption organizations were among those particularly affected.

One of the most striking examples was the local partner of Transparency International — the civic association Transparency Azerbaijan. Since the early 2000s, the organisation had provided legal assistance and public education on corruption-related issues. But beginning in 2014, new government-imposed barriers to registering foreign grants brought its activities to a halt.

In August 2017, the organization announced the closure of its Baku office. It was reported that the USAID-funded “Azerbaijan Partnership for Transparency” project — including both the main office in Baku and regional anti-corruption centres — would cease operations. The reason was that a new grant had not been registered by the Ministry of Justice.

The closure of Transparency Azerbaijan further weakened civil society’s role in the country’s fight against corruption.

As a result, today, almost no international anti-corruption organisations or donors remain actively engaged in Azerbaijan. This has severely undermined independent public oversight and international support for anti-corruption efforts.

Transparency International’s Corruption Perceptions Index reflects this reality: in 2024, Azerbaijan scored just 22 points, ranking 154th out of 180 countries (0 = highest corruption, 100 = lowest). The result highlights the systemic nature of corruption in the country — and the climate of impunity that has taken hold in the absence of independent voices.

Conclusion: Corruption as the norm, impunity as the rule

The scale of financial misconduct in Azerbaijan continues to grow year by year — yet those responsible remain untouched. Public reports do not translate into real mechanisms of accountability.

With an independent press dismantled, international organisations sidelined, and a judiciary under political control, anti-corruption efforts exist only in official rhetoric.

Meaningful change is only possible with genuine political will, an independent judiciary, and strong public oversight. Without these, corruption will remain a routine feature of Azerbaijani life.

For now, what remains is a judiciary that follows political orders, a silenced civil society, and a political will that serves only the ruling elite.