Could Azerbaijan join the Abraham Accords?

Azerbaijan and the Abraham Accords

The diplomatic initiative known as the Abraham Accords, launched by the United States in 2020, has not yet been signed by Azerbaijan, despite its close ties with Israel.

The Abraham Accords, a diplomatic initiative launched by the United States in 2020, were framed by the Trump administration as a historic peace effort. Donald Trump emphasised that the inclusion of more Middle Eastern and Central Asian countries would bring greater peace and stability to the region. One of the administration’s key goals was to ease tensions in the Middle East (or Western Asia) by promoting the normalisation of relations between Israel and what it called “moderate” Arab states.

As part of the initiative, countries that join are promised access to advanced technologies and new trade opportunities. The main factor bringing the sides together is their shared perception of Iran as a common threat in the region. In this context, Trump’s initiative aimed to bring Israel and Arab countries closer together through common interests — primarily countering Iran — and to reshape the regional balance of power.

Although Azerbaijan is one of the few Muslim-majority countries with strong ties to Israel, it has so far stayed out of the Abraham Accords.

So why does official Baku remain on the sidelines? What political and strategic considerations are behind this decision?

It’s these questions that Azerbaijani political analyst and head of the Atlas Research Centre, Elkhan Shahinoglu, seeks to answer. Shahinoglu breaks down why Azerbaijan hasn’t joined the Abraham Accords and what’s really driving that decision.

Azerbaijan’s position and Shahinoglu’s analysis

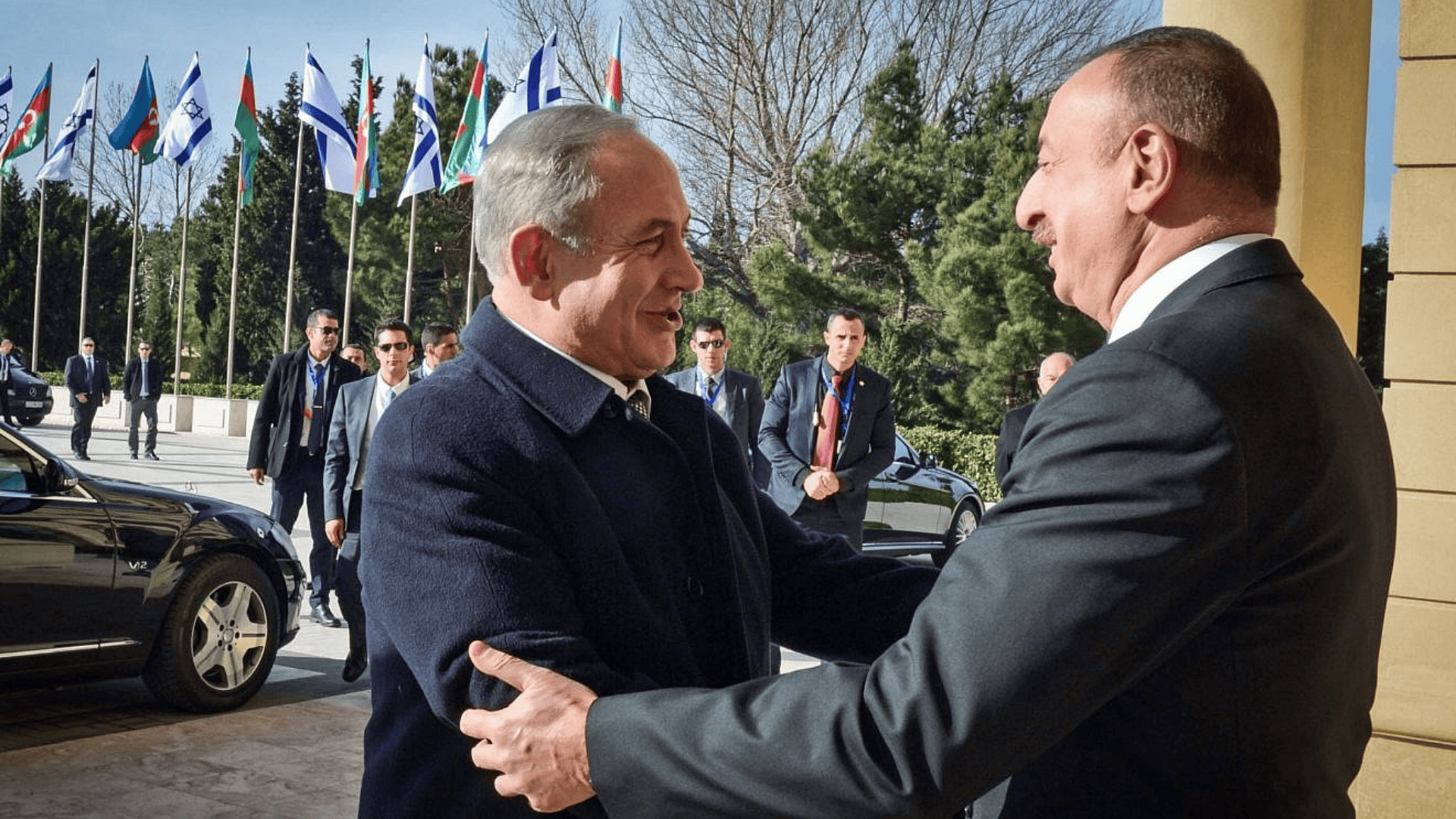

Azerbaijan has pursued an independent foreign policy for years, maintaining a strategic partnership with Israel while also keeping strong ties with the Islamic world. Its cooperation with Israel spans defence, energy, and security, but at the same time, Baku has remained an active member of the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation and consistently backs Palestinian rights. Relations with neighbouring Iran, rooted in historical and cultural ties, also remain a priority.

Within this delicate diplomatic balance, the question of joining the Abraham Accords requires careful consideration.

When the accords were signed in 2020, there was speculation that Azerbaijan might be next. Reports suggested that US officials held talks with Baku at the time, but the government avoided public commitments and stayed cautious.

So why this reluctance?

According to Elkhan Shahinoglu, Azerbaijan currently sees no practical need or political advantage in joining the accords.

According to Shahinoglu, Azerbaijan already has extensive ties with Israel, so signing up to a separate agreement would be little more than a symbolic step.

“Azerbaijan has diplomatic relations with Israel. And beyond that, there are deep connections across multiple areas,” he says. “In this context, does Azerbaijan really need the Abraham Accords?”

In fact, Azerbaijan recognised Israel back in 1992, and official ties have only grown stronger since. In 2023, Baku opened an embassy in Tel Aviv. The two countries trade billions of dollars’ worth of goods each year — mainly oil exports from Azerbaijan to Israel — and Baku purchases advanced weaponry from Israel for its defence sector. Senior officials from both sides regularly exchange visits.

In practical terms, Azerbaijan is already benefiting from everything the Abraham Accords offer, on a bilateral basis. Shahinoglu underlines this point, arguing that with such a close partnership already in place, joining a broader framework agreement would be largely symbolic.

What are the Abraham Accords?

The term refers to a series of diplomatic agreements signed in 2020. On 15 September that year, at a formal ceremony in Washington, Israel signed official normalisation deals with the United Arab Emirates and Bahrain. These Gulf states became the first Arab countries since Egypt and Jordan to recognise Israel and establish diplomatic ties.

The name “Abraham Accords” refers to the prophet Abraham, a shared patriarch in Judaism, Islam and Christianity, symbolising peace and common heritage.

At the heart of the agreements is the establishment of official diplomatic, economic and cultural relations between Israel and the signatory Muslim-majority countries, marking an end to decades of hostile rhetoric. Under the accords:

- Israel and the Arab signatories recognise each other and agree to open embassies;

- deals are signed to expand cooperation in trade, investment, tourism, aviation, security and technology;

- the US acts as a mediator, offering incentives such as lifting sanctions on Sudan or recognising Morocco’s sovereignty over Western Sahara.

The accords signalled a shift in the region, with some Islamic countries effectively recognising Israel and opening a new chapter in regional diplomacy. The move was widely seen as a landmark achievement. The Trump administration described it as a “new dawn” for the Middle East (or West Asia) and framed it as a major step towards peace.

Since mid-2025, the US has been pushing to expand the scope of the Abraham Accords. Countries such as Saudi Arabia, Oman, Kazakhstan and Azerbaijan are now being floated as potential next participants. But joining is not straightforward — each country has its own political landscape and strategic interests to consider.

Trump’s initiative and goals

US president Donald Trump, the architect of the Abraham Accords, introduced a new approach to the Middle East during his first term in office (2017–2021), breaking from traditional peace negotiation models. His son-in-law and adviser, Jared Kushner, led the development of an economic plan called Peace to Prosperity, which was presented at an international conference in Bahrain in 2019.

The plan was built on the idea that geopolitical conflicts could be eased through geo-economic incentives. In other words, even with the Israeli-Palestinian conflict at a stalemate, countries in the region could still normalise ties with Israel in exchange for economic benefits.

Trump argued that the more countries in the Middle East (or West Asia) establish official relations with Israel, the better the chances of lasting peace in the region. He went further, calling on all Muslim-majority countries to join the initiative.

In a 2025 statement, Trump declared that the Iranian nuclear threat had been eliminated and said:

“It’s very important to me right now that all countries in the Middle East join the Abraham Accords.”

He claimed this would be the key to lasting peace in the region.

By mid-2025, Trump had renewed his push, aiming to bring more Muslim-majority states, including Saudi Arabia, into the fold.

But there are also key factors making it harder for Azerbaijan to sign up.

Elkhan Shahinoglu points to several geopolitical issues Baku needs to weigh carefully.

The Turkey factor

“Azerbaijan’s strategic ally, Turkey, isn’t likely to join the Abraham Accords under current conditions,” says Shahinoglu.

While Turkey has taken steps to rebuild ties with Israel — including military cooperation until the late 2000s and the restoration of diplomatic relations in 2022 — the government of Recep Tayyip Erdoğan has stopped short of forming a deeper alliance. Since the 2023 war in Gaza, Ankara’s stance towards Israel has become increasingly critical, both politically and across Turkish society.

In this context, Turkey’s decision to stay out of the Abraham Accords gives Azerbaijan further reason to hold back.

Ankara and Baku tend to move in step on key regional issues, and Shahinoglu points out that taking part in an initiative that excludes Turkey could create a sense of imbalance.

He adds that coordination between the two countries is essential in any regional framework — and when it comes to the Abraham Accords, Baku prefers to remain aligned with Ankara.

The Palestinian issue and the war in Gaza

Another major factor, Shahinoglu says, is the ongoing Israeli-Palestinian conflict.

“As long as the humanitarian crisis in Gaza continues and Israel refuses to recognise Palestinian statehood, it will be difficult for Azerbaijan to join the accords,” he explains.

The 2023 war in Gaza, which killed thousands of civilians and devastated local infrastructure, sparked strong reactions around the world — including in Azerbaijan. While some in the country voiced support for Israel, many were deeply angered by the scale of the destruction.

Officially, Baku condemned attacks on civilians and reaffirmed its support for resolving the Palestinian issue through a two-state solution based on UN resolutions. In this climate, forming a formal alliance with Israel — especially under US sponsorship — risks provoking domestic backlash and damaging Azerbaijan’s standing in the broader Islamic world.

Shahinoglu argues that Baku is right to be cautious. Taking such a step without progress on Palestinian statehood or an end to the crisis in Gaza could be widely misinterpreted and harm the country’s image.

Azerbaijan has also consistently emphasised Islamic solidarity — partly due to longstanding support from the Organisation of Islamic Cooperation over the Khojaly tragedy. As a result, the Palestinian question remains especially sensitive, making it politically difficult for Baku to sign a new multilateral deal with Israel while the conflict remains unresolved.

The Iran factor

While Shahinoglu doesn’t mention Iran directly, it’s clear from the context that Tehran is a major geopolitical consideration for Azerbaijan.

The two countries share more than 700 kilometres of border and deep historical and cultural ties. Although tensions have flared in recent years — particularly between 2021 and 2022 — Baku has tried to avoid open confrontation with Iran. At the same time, the Abraham Accords are widely seen as forming the basis for a regional bloc aimed at containing Iran. Both the US and Israel have made no secret of their intention to isolate Tehran through these agreements.

Against this backdrop, any move by Azerbaijan to join the accords would almost certainly trigger a hostile response from Iran. Even now, Iranian officials and state media regularly criticise Azerbaijan’s close ties with Israel, accusing Baku of cooperating with the “Zionist regime.”

If Azerbaijan were to formally sign on, tensions with Tehran could escalate sharply, with the risk of retaliation.

This uneasy neighbourhood makes Iran a major factor in Baku’s cautious approach.

Shahinoglu also points out that while Washington is keen to bring Azerbaijan into the fold, joining simply to please the US would be a mistake — especially if the potential fallout outweighs the benefits. In this case, the costs would likely include a serious deterioration in relations with Iran and greater risks to national security.

Central Asia and the Turkic world

Elkhan Shahinoglu notes that Azerbaijan is not alone in its cautious stance. Other countries, such as Kazakhstan, are in a similar position.

“Astana is also taking a wait-and-see approach to the Abraham Accords,” he says.

Several Turkic and Muslim-majority countries — including Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan — maintain good relations with Israel but remain wary of joining the initiative. Despite this, Washington is applying similar pressure on them, aiming to bring Central Asian republics into the fold.

The broader goal is to expand the ring of containment around Iran while keeping these states within the US sphere of influence and away from Russia and China.

But so far, neither Astana nor Baku is rushing in. This suggests that Turkic states are broadly aligned in their approach. As a member of the Organisation of Turkic States, Azerbaijan is aware of its geostrategic weight and prefers not to act alone. On the contrary, it has been strengthening its ties with Central Asia, seeing the region as a political bridge. If a decision is made, Shahinoglu suggests, it’s likely to be a coordinated one.

Israel’s position

Israel, for its part, is not pressuring Azerbaijan to join the Abraham Accords.

As Elkhan Shahinoglu puts it, “Tel Aviv is primarily focused on bringing in Arab countries and hasn’t made any specific demands of Azerbaijan.”

This is reflected in public statements by Israeli officials. In one interview, a former Israeli ambassador to Azerbaijan described the country as a strategic partner and said that there was no need for Baku to sign a multilateral agreement to prove it.

Azerbaijan is already considered a close friend of Israel, and Tel Aviv sees no reason to push Baku into a move that could expose it to unnecessary risk.

The current bilateral arrangement works well for both sides, and that cooperation is valued.

Shahinoglu echoes this view: “Azerbaijan and Israel don’t need anything more than continued bilateral partnership.” In other words, even without joining the Abraham Accords, the relationship is already strong — and doesn’t require an additional framework.

At the same time, Shahinoglu suggests that Azerbaijan isn’t closing the door completely. If circumstances change — for example, if there’s real progress in the Israeli-Palestinian peace process or if key allies like Turkey shift their position — Baku may reassess. In fact, it appears Azerbaijan is even trying to play a quiet role in facilitating reconciliation between Tel Aviv and Ankara, which could help lower regional tensions.

For now, though, a cautious wait-and-see approach remains the most pragmatic option. Azerbaijan continues to send friendly signals to both Washington and Tel Aviv while maintaining a delicate regional balance. This strategy allows Baku to sustain its strategic partnership with Israel while preserving its credibility in the Islamic world.