Who is challenging the ‘last dictator in Europe’ – Belarus heads to the polls in presidential elections

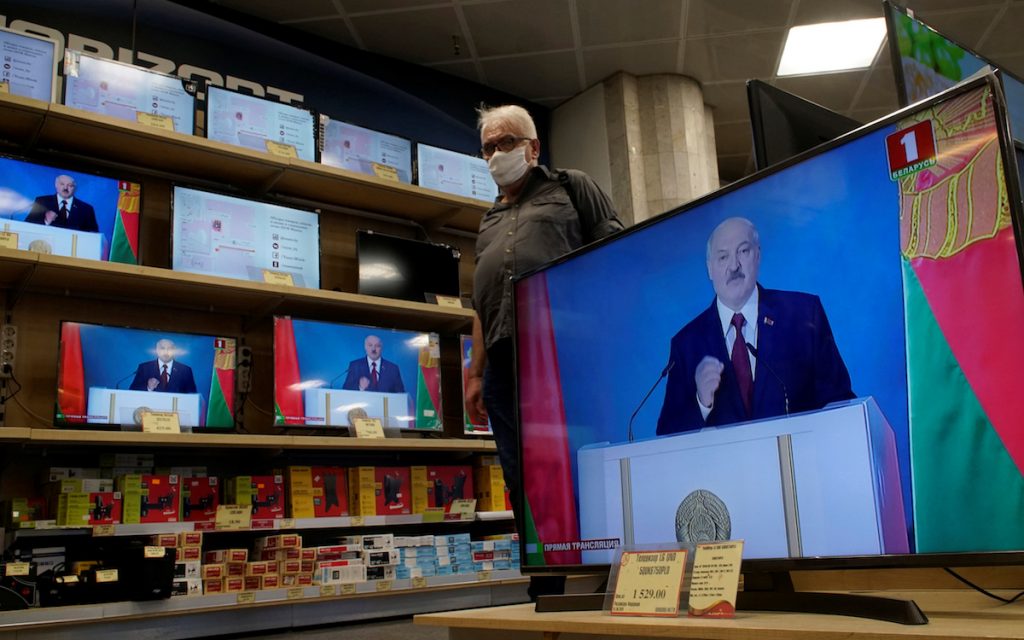

Belarus is set to elect a new president on August 9. Current president Alexander Lukashenko, who has been in power for the last 26 consecutive years, faced serious challenges during his election campaign — the opposition took to the streets en masse, and the authorities arrested both demonstrators and presidential candidates. And just one week before the elections, “Russian mercenaries” were discovered and arrested.

Who exactly is challenging the “last dictator in Europe” and what are the possible ways the election might turn out?

Tsikhanouskaya – the non-political candidate

37-year-old Sviatlana Tsikhanouskaya is the only openly-announced opposition candidate on the ballot.

Aside from her and Lukashenko himself, the other presidential candidates are Anna Kanopatskaya, Sergei Cherechen and Andrei Dmitriev.

However, those dissatisfied with the regime are rallying around Tsikhanouskaya.

• Belarus: mass arrests, clashes with the police, “foreign mercenaries” ahead of elections

• How coronavirus forced Belarusian officials to be more communicative

She has no previous experience in politics, but her election rallies pull in crowds of thousands – something never before seen in Belarus. In her speeches, she asks people to vote for her not because of her political platform, but for the potential change she could bring and the opportunity to restore people’s right to elect their leader.

Tsikhanouskaya became a reluctant candidate after her husband, popular video blogger Sergei Tsikhanousky, who was going to run for president, was not allowed to participate in the elections and then was arrested.

In addition to Tsikhanousky, popular opposition candidate Viktor Babariko was also arrested. Another candidate, Viktor Tsepkalo, was forced to leave Belarus. But their campaign teams are supporting Tikhanovskaya with their resources.

Arrests and Repression

The Belarusian authorities have responded to the active opposition among the public by arresting demonstrators, activists and journalists on an almost daily basis.

DJs Kirill Galanov and Vladislav Sokolovsky were detained on the evening of August 6 during an event organized by the authorities for playing the song “We are waiting for change” by Viktor Tsoi. They were sentenced to 10 days in jail for petty hooliganism and disobeying the police.

On the afternoon of August 7, Current Time TV journalists — citizens of Russia and Ukraine Irina Romaliyskaya, Ivan Grebenyuk and Yuri Boronyuk — were detained at the Minsk Hotel in the center of the Belarusian capital. They were forced to leave Belarus.

Police continued to arrest picketers in several cities around the country. Drivers passing by were fined for honking.

Lukashenka compared these demonstrations to the Ukrainian Euromaidan Movement: “I want to warn all these protesters that there will be no Maidan in Belarus”.

Has the regime lost to the coronavirus?

Lukashenko used his security officers to force Belarusians to come to terms with his endless presidential term. Political apathy was running rampant in society, so no one expected anything from the 2020 elections. But the situation has changed, explains political scientist and journalist Valery Karbalevich to news source Zaborona.

“In 2006 and 2010, a traditional democratic electorate oriented towards European values opposed Lukashenko. Now the other part of the population that holds different ideals is expressing their dissatisfaction, but they also do not like Lukashenko.”

They played Lukashenko’s main trump card against him — the stability, which has turned to stagnation during his time as president. But Lukashenko dealt a powerful blow to his own image with his rhetoric and actions during the COVID-19 pandemic. At first, the President denied the coronavirus, convinced that because he did not see it, it does not exist at all, then suggested that “tractor therapy” and working in the fields would cure coronavirus, and also accused doctors of spreading COVID-19. People expected no assistance from the government, writes the Belarusian journalist Liza Moroz.

In the pre-election polls conducted by Belarusian Internet publications TUT.BY and Onliner, Alexander Lukashenko received only 3–6%. The nickname “Sasha 3%” stuck, although, of course, his rating is higher.

In April, the Institute of Sociology reported that 24% trusted Lukashenko to head the country. By the end of June, some media published information stating that Lukashenko’s rating was at 76%, although experts expressed doubts about the reliability of these figures.

Is the romance with Russia over?

During this election campaign, Lukashenko focused for the first time not on “Western puppet masters”, but on the Russian ones. He used this rhetoric in relation to the candidate Babariko, who headed the Belarusian branch of the Russian Gazprombank for 20 years.

Since 2018, the seemingly ironclad relationship between Russia and Belarus has deteriorated. Lukashenko wanted a preferential price for gas and to continue receiving oil supplies from Russia at Russian domestic prices, which was of great importance for the country’s economy. However, they never managed to come to an agreement with Russia on gas and oil, as Moscow demanded deeper integration from Minsk.

Officially, Belarus and Russia form a Union State. However, the parties have yet to agree on a single currency or unified political structures.

Lukashenko himself has publicly rejected the idea of unifying with Russia and forming one government more than once.

“Lukashenka has formed pretty good relations with the West in recent years. And with Russia, on the contrary, there have been consistent conflicts the last year and a half, including in the energy sphere. It is very convenient for him to use this issue as context. This allows Lukashenka to position himself as a defender of sovereignty,” explains political observer Artem Shraibman.

On July 29, the Belarusian state media reported on 200 soldiers from a foreign private military company. Of these, 32 were detained who are associated with the so-called Wagner group. Some soldiers from this company even fought on the side of pro-Russian militants in Donbass.

What to expect after the elections

Journalist Valeriy Karbalevich believes that the election campaign has become a catalyst for forming a civil society in Belarus. But it is not known whether this process will continue after the elections.

Karbalevich does not exclude the possibility that we may see a repeat of 2010, when tough repressions quashed citizens’ enthusiasm.

“Society cannot remain in an active politicized state for long. I fully acknowledge the possibility that if the authorities crush the opposition on August 9-10, then the situation may come to a standstill for the next 5 years.”

Artem Shraibman draws two scenarios for if Lukashenko remains in power. If on August 9 and 10 everything goes smoothly, without mass arrests, and the current government’s trauma heals quickly, the government may not tighten its grip for many years.

“In a more pessimistic scenario, they may tighten their fist by exerting pressure on the press. Lukashenko has already mentioned withdrawing accreditation from foreign media sources. The pressure on bloggers will continue, as well as the traditional criminal and administrative pressure on politicians and activists.”