Female photographers compare themselves to firefighters and policemen

Female photographers who have been working in the Armenian media sector over the past decade have been breaking stereotypes just with their mere presence on the market. More than that, professional female photojournalists have raised and covered social problems, thus spurring on the development of documentary photography.

“We try to show problems that are regarded as taboo in our reality, themes that have long been concealed beyond life’s array. We are therefore often told that we capture the mire of life and bring it out into the open,” says Nazil Armenakyan, a documentary photographer. She was among the first female photographers who appeared in the media sphere in the early 2000s”.

• Women-only factory tackles unemployment in vulnerable Armenian families

• The Karabakh conflict through the stories of three women

She recalls that back in 2002, she took a job at the Armenpress news agency. There were no female photographers at the time:

“Field veterans were looking at me with suspicion; there was a question in their eyes: Can you handle the job? The first year was a rather hard one. I had to gain experience and, at the same time, prove to them on a daily basis that women can do photography,” says Armenakyan.

She openly admits that even her husband was doubtful about that, constantly reminding her that she had chosen a hard job for a woman.

“It was my father who supported my intention to get engaged in photography. He was the only one who saw my inner potential, who believed in me, who convinced my family members, who helped and supported me in every possible way,” says Armenakyan, the mother of two sons.

Anush Babajanyan, who has been in documentary journalism since 2008, notes that when she travels for photo-shoots, especially to marzer (the provinces) or Nagorno-Karabakh, she could feel that her presence unsettled the locals.

“During the April war, when I traveled to Nagorno-Karabakh where the situation was extremely dangerous in those days, I could see the question on people’s faces: ‘Is it a proper place for you?’ Or they didn’t take me seriously and would say: ‘Don’t you have a husband and children? Go home.’ And when they learned that I was married, they would tell me: ‘So, why on earth have you come here?’ People simply forget that it’s our job,” says Babajanyan.

She is the mother of two children. Babajanyan compares photojournalists’ work to that of firemen or policemen, adding that:

“Those people work exposing themselves to danger and there are many women among them. I think we should be treated the same way.”

Some female photographers note that it’s particularly hard to get a job in the mass media sector because editors usually prefer men.

Anahit Hayrapetyan, a photographer and a mother of three says that most news agencies give preference to men:

“If an employer says he would like to have a male photographer, it basically implies that a woman won’t be able to turn up to work any moment at his beck and call. Mind that there may be some unexpected circumstances. In Armenia the reality is harder for women: household, family, children, work… There are more men among the photographers worldwide.

“The world press has recently been covering this issue continuously, encouraging editors to employ female photographers so as to maintain balance in world photojournalism. Our photos are our voices. One of the photographers launched a website that presents only female photographers’ works.”

When comparing the past 10 years, Lilian Galstyan, a Panorama.am photographer notes that the stereotypes in this field are being broken broken:

“Just a few years ago everything could be felt in the cameramen’s sharp glances and attitudes. They were shoving, not giving room for one to stand and take a shot. Now they themselves reserve us places, and if it’s a protest rally or clash with the police, they try to protect us.”

Unlike documentary photographers, Lilian Galstyan captures news every day. She likes being in the thick of things:

“I don’t choose what to shoot: I take photos of everything that happens. In the rain and snow, protest rallies, pickets, protestors and police clashes. You don’t choose whether the news is dangerous or not. You just take photos. But there is one thing: men have a better understanding of how to protect themselves in those clashes. In such moments women are hindered by their emotions.”

Female documentary photographers believe they are trusted more than men.

“I think it’s easier for us as women to work in the areas of photography where human relations are of primary importance. You start your work by managing those relationships. People trust us more than male photographers. In addition, there are themes that only a woman’s camera can capture, be it violence or LGBT community problems,” explains Nazik Armenakyan.

Piryuza Khalapyan, a documentary photographer, notes that men mostly prefer taking snapshots:

“They prefer glossy photos. Their work resembles more ‘nice’ cover photos like celebrities’ photos. They are more superficial in their work. Unlike them, I can travel to a Yazidi village and talk to Yazidi children for hours before I start working,” says Piryuza.

In 2012, Nazik Armenakyan, Anahit Hayrapetyan, Anush Babajanyan and Piryuza Khalapyan united their efforts and set up the Armenian Documentary Photography Center ‘4+’.

“Our objective isn’t just to take good photos. We try to spur the development of documentary photography in Armenia. We organize training courses, master-classes and exhibitions to develop the market,” says Nazik Armenakyan.

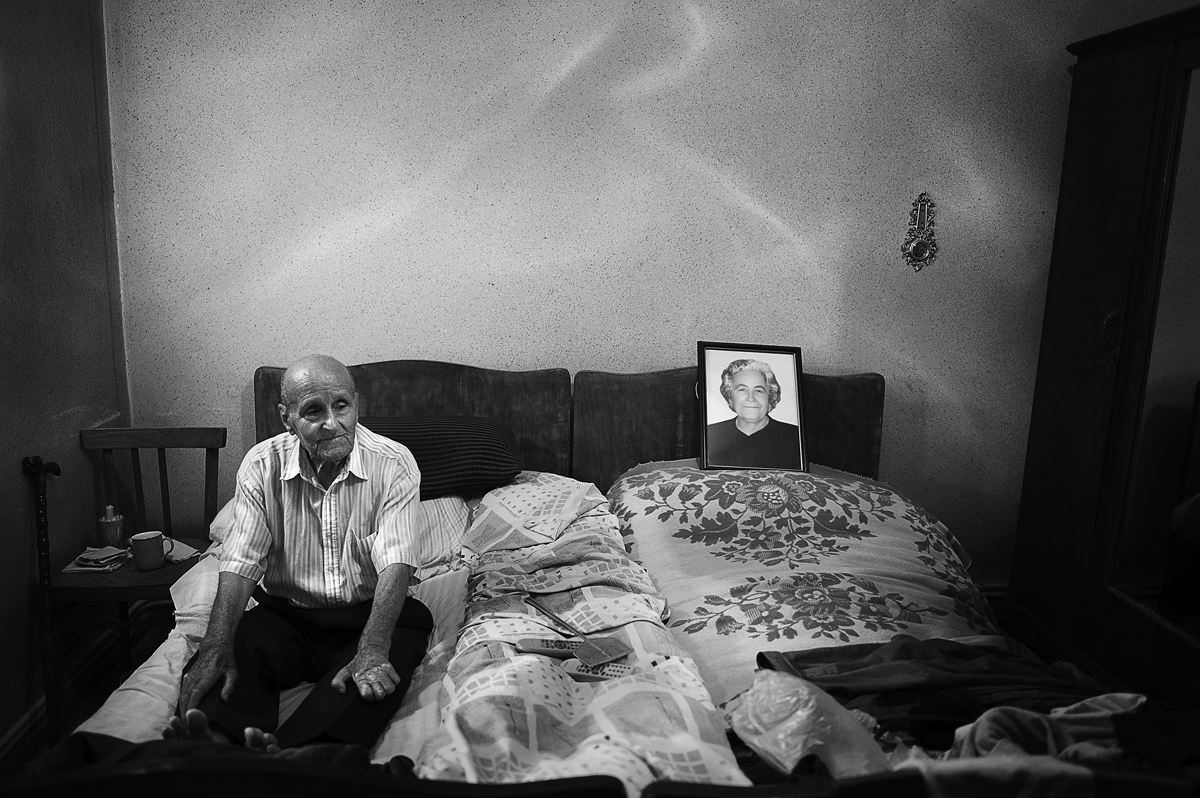

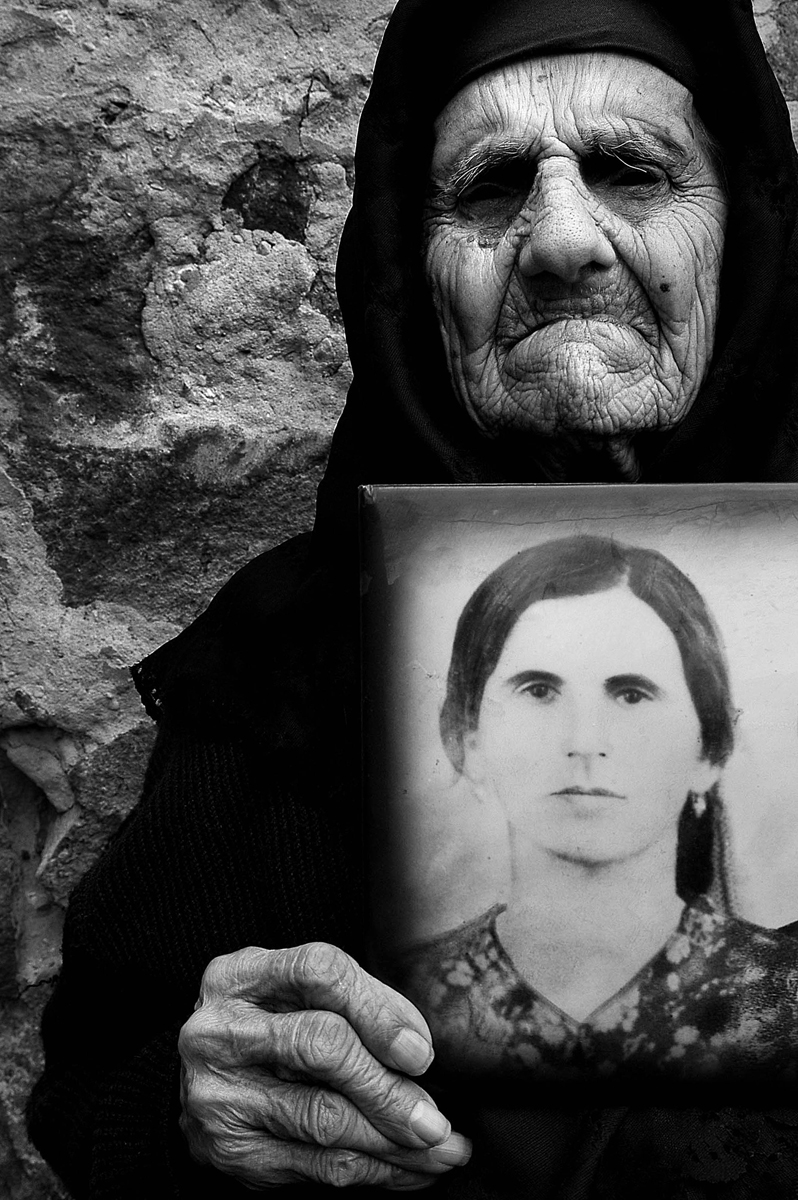

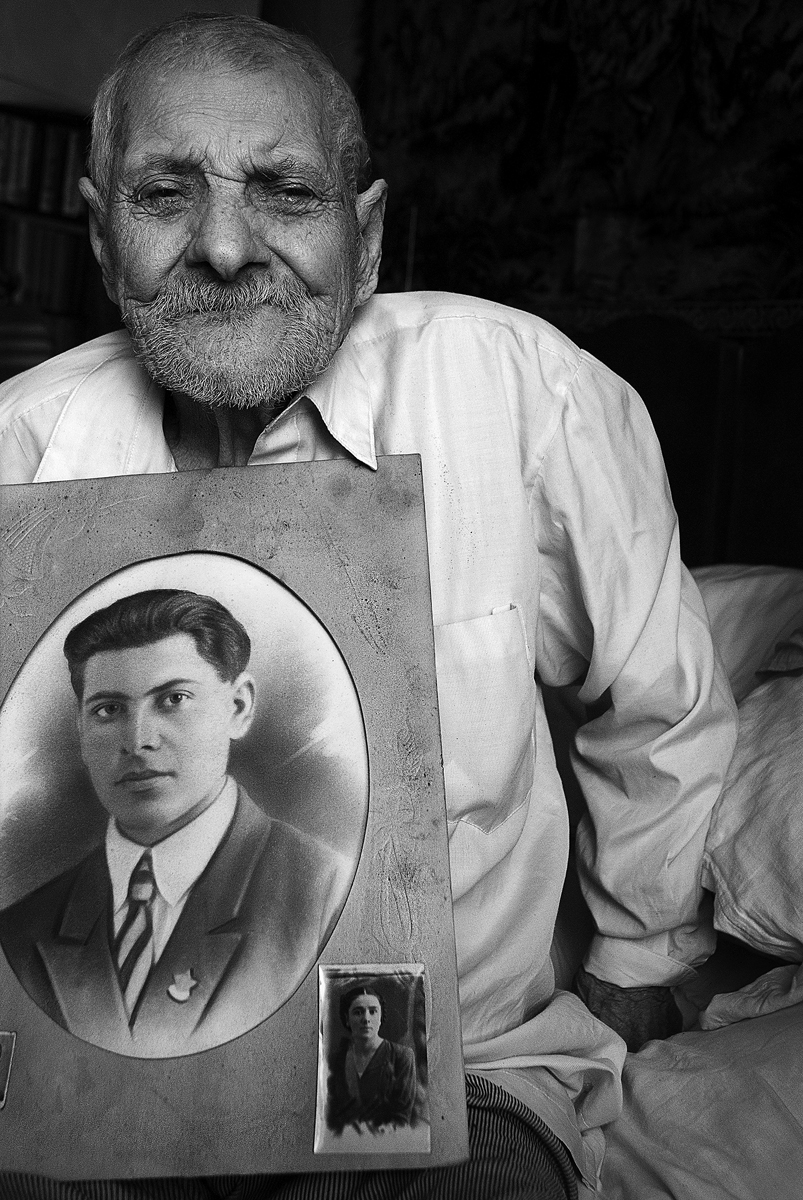

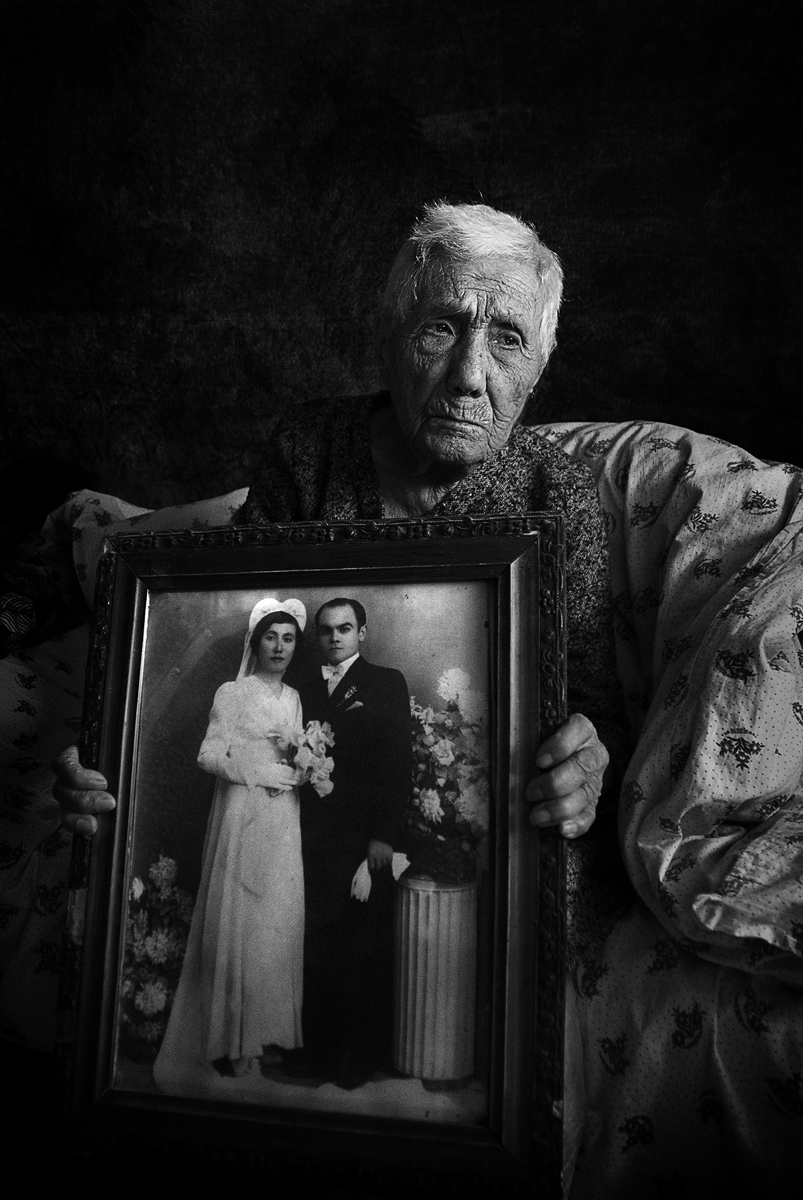

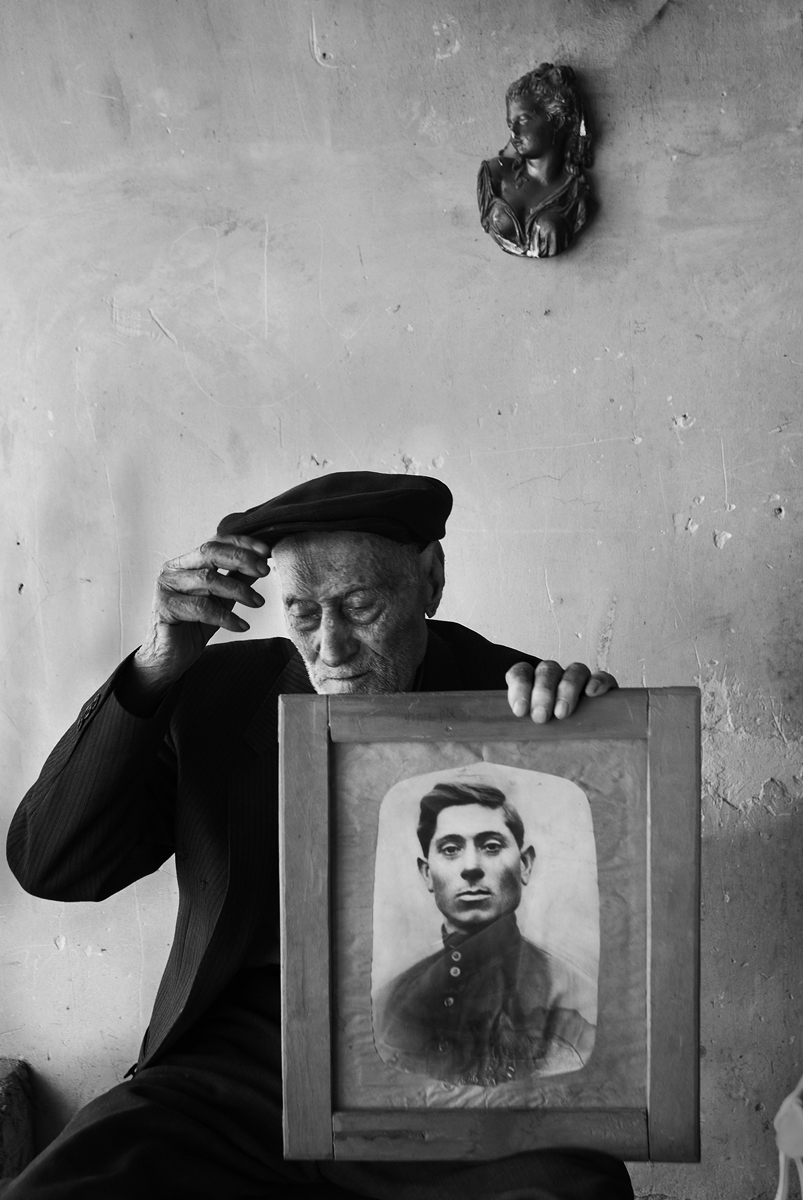

Documentary photographers believe that through their work they delve into a different strata of society and raise many socio-economic problems. They enter places where they are often not expected, trying to filter human feelings and emotions with their camera lenses and present them to the public.

“Our exhibition aptly named ‘Mother Armenia’ wasn’t a coincidence; it’s common knowledge that we have Mother Armenia, a wonderful country. But we have shown the reverse side of Mother Armenia, which is often full of uncovered problems and concerns.

“I worked with the LGBT-community for quite long and they admitted that if I had been a man, they wouldn’t have let me get so close, wouldn’t have opened up to me and wouldn’t have communicated with me. Actually, there is a problem with whom to trust and why. People understood that I wasn’t there for the sake of sensation.”

The photographer regards it as an advantage to stay in the theme for a longer period of time:

“The main job is to develop relations. Through our cameras we closely observe people’s lives day and night, we live with their concerns and hardships, we try to understand them and show all that in our photographs.”

Anahit Hayrapetyan, an author of a photo series on domestic violence issues, points out that women are more diligent in work, spending more time on it even if it’s not paid:

“As a woman, I started looking at the domestic violence problem from the same perspective. I was wondering whether my relatives and friends were facing the same problem. None of the male photographers covered that issue. I think it would be more difficult for them. It was easier for me as a woman to talk to other women – they trusted me.”

Female photographers proudly claim that they have brought world renown to Armenia thanks to their photos.

“We’ve done a very good job over the past year. Our photos have been published in the New Yew York Times and the Washington Post. We’ve been cooperating with international agents and editors and it’s a great experience for us,” says Anahit Hayrapetyan.