Kremlin’s soft power plan for Azerbaijan: “Hundreds of millions of dollars wasted”

Russia’s soft power in Azerbaijan

The Insider reports that secret Kremlin papers have raised serious alarm over the absence of organisations in Azerbaijan that defend Russia’s interests. The documents explicitly call for creating Russian-language NGOs in the country and strengthening those that already exist.

Russian president Vladimir Putin has abolished the department for interregional and cultural ties with foreign countries, replacing it with a new office for “strategic partnership and cooperation.”

The official explanation was “optimisation,” but the move has been widely seen as an admission of failure after 20 years of attempts at “soft power” across the post-Soviet space, including in Azerbaijan.

One of the key overseers of the new department is Dmitry Kozak, a senior official in the presidential administration. He supervises the “near abroad” portfolio, including Azerbaijan, and has prepared reports on regional developments. According to investigations, it was at Kozak’s initiative that plans were drawn up to strengthen or recreate NGOs in Azerbaijan to promote Russia’s interests.

The department, created back in 2005, had aimed to prevent “colour revolutions” in the post-Soviet space and shape public opinion in ways favourable to the Kremlin. Its remit covered Ukraine, Armenia, Azerbaijan, Georgia and other former Soviet republics.

“As much as a hundred million dollars was invested in friendship, but it all went to waste”

Part of The Insider’s investigation concerning Azerbaijan shows that after 2005 — following Ukraine’s Orange Revolution — the Kremlin sought to strengthen its influence in Baku through NGOs, cultural projects, the promotion of the Russian language and educational initiatives.

The secret reports recommend “reinforcing the presence of Russian NGOs in Azerbaijan” and, if necessary, creating new ones. Priority areas are listed as border regions, youth and students, education, the Russian language, cultural projects and journalism forums. The investigation also highlights the role of the relevant department within Russia’s presidential administration and its affiliated figures in carrying out this agenda.

The Insider publishes a fragment of a secret report from the “Azerbaijan” section presented to Kozak:

“It is advisable to strengthen the presence of Russian NGOs in Azerbaijan. There is clearly no genuine civil society organisation there promoting Russia’s position. Reviving existing NGOs or creating new ones in Azerbaijan would, in the long term, help build a soft power tool for projecting Russian influence.

The main focus of NGO work could be on border areas, youth, student organisations, education, the Russian language, cultural projects and journalism forums. NGO projects should not be limited to major events but must consistently ‘penetrate’ Azerbaijani society and be present in the media.

Work with organisations of compatriots must be streamlined and systematised, and, if necessary, their leadership replaced.”

A former staffer from the department told The Insider:

“By my count, more than a hundred million dollars were poured into friendship with Azerbaijan, but it all disappeared into a black hole. Much of it was done just for show or in the spirit of balalaika diplomacy. And it was always about drinking, drinking and more drinking.”

According to the investigation, Azerbaijan hosted seminars, round tables, “schools of journalism” and lavish exhibitions, including one titled Heydar Aliyev. Personality. Mission. Legacy.

But many of the projects were carried out only formally, “for the report.” This approach is often described as “balalaika diplomacy” — a mocking term for Moscow’s habit of staging concerts, cultural showcases and vodka-fuelled receptions instead of building genuine influence.

Official Moscow and Baku declined to comment.

A failed soft power policy: “For Azerbaijan it was a kind of happy corruption”

As the secret reports admit, the Kremlin’s soft power strategy in Azerbaijan failed to produce results either politically or socially. More than $100 million was channelled into “friendship and cooperation” with Azerbaijan, yet the funds created no real influence.

The Azerbaijani outlet BizimYol wrote that Valeriy Chernyshev, the official in charge of Azerbaijan for the department of interregional and cultural ties, was in fact an officer of Russia’s military intelligence agency, the GRU.

“Just imagine: the task of building and supervising Russia’s soft power towards Azerbaijan was given to GRU officer Chernyshev (!). In other words, the job of fostering ‘cultural ties’ with post-Soviet countries was entrusted to the military (?!).

And how exactly were these military men supposed to build so-called soft power in the countries they oversaw?

Of course, we are talking about NGOs, media outlets and probably political parties. Imagine civic groups, media and even politicians defending Russia and funded by Russia — all overseen by senior GRU officer Valeriy Chernyshev! He had access to information about top Azerbaijani officials, the military, civic and political figures. How? From Azerbaijan. That means Russia’s GRU, through Chernyshev, was running an intelligence network in the country.”

No less than $100 million was spent from the Russian budget. The result? Zero. Why zero? Because the money was simply stolen. Russian “curators,” together with Azerbaijani NGO figures, media representatives and others, built a straightforward corruption scheme that lulled Putin into complacency.

For Azerbaijan, this could almost be called “happy corruption.” At least Russian officials and their local agents only looted Moscow’s state funds — $100 million in total.

As one former insider told The Insider:

“A lot of it was done purely for the paperwork or in the spirit of balalaika diplomacy. It was drinking, drinking and more drinking, all the time.”

So this is what Putin’s “soft power” looked like. This is what Russian intelligence amounted to. Even “cultural” ties were built in the crudest, clumsiest way — and they were helped along by local collaborators working against their own country.

Fortunately, they failed to achieve their aims. But even so, Azerbaijani informants — “agents of influence” — were collaborating with Russian intelligence against their own country.

Now the key question is: will Azerbaijan’s State Security Service, the prosecutor’s office and other authorities act on this information?

And will the names of Russia’s Azerbaijani agents — the “soft power corruptionists” — ever be revealed?”

Attempt to influence through the media

One of the Kremlin’s soft power tools was the media. Moscow funded outlets such as Sputnik Azerbaijan and other Russian-language platforms in an effort to push its line in the country. But because of tight controls by the Azerbaijani authorities, the reach of Russian media remained limited. Pro-Russian messages were mainly relayed through state-controlled media or in official statements.

Although political relations between Azerbaijan and Russia had appeared relatively stable since the late 2010s, a series of events between 2022 and 2025 heightened tensions and underscored the futility of Moscow’s soft power. This became especially clear after Russia’s war against Ukraine in 2022, as Baku stepped up its balancing policy amid the shifting geopolitical climate.

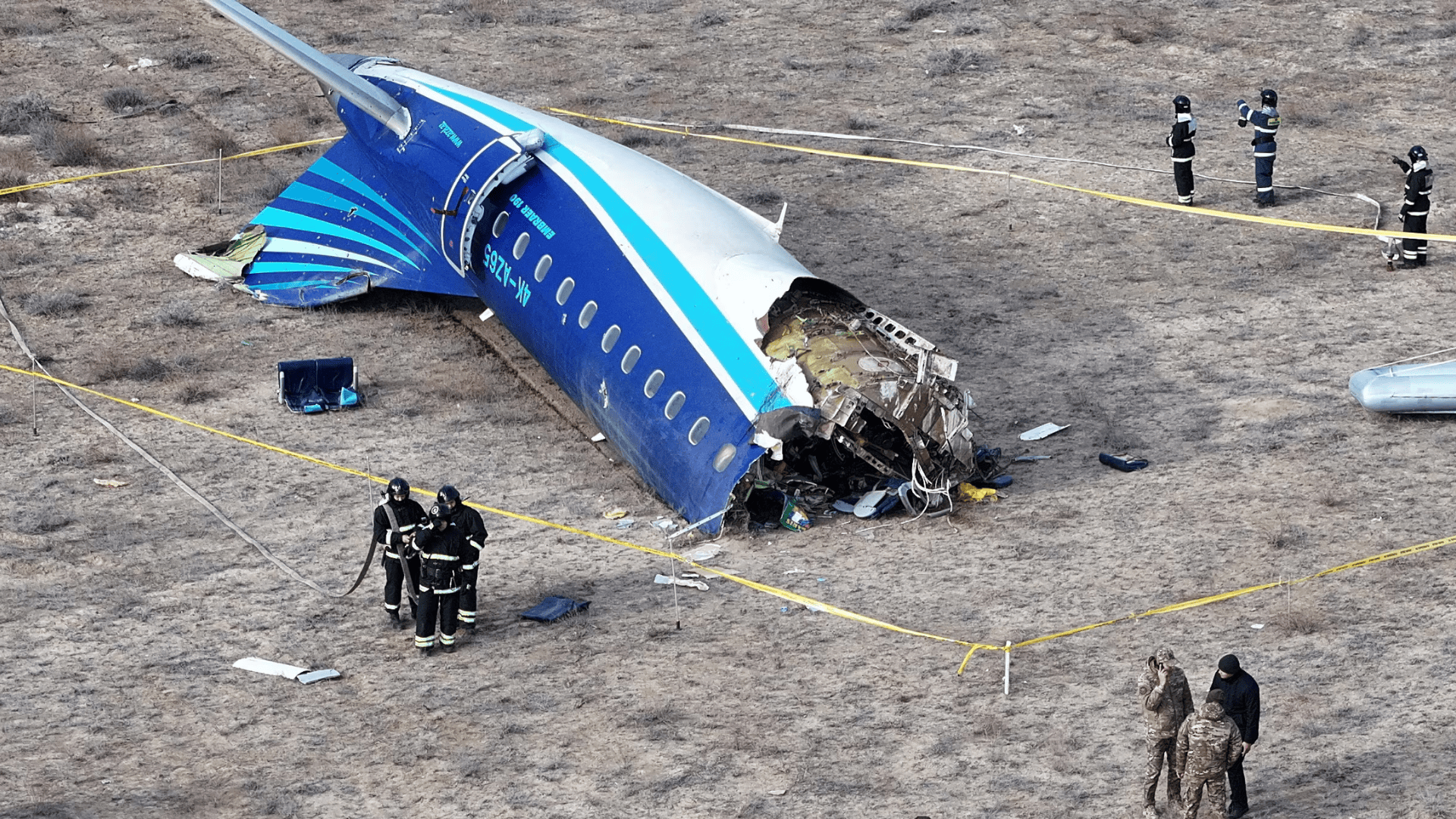

In February 2022, the two countries signed a Declaration on Allied Interaction. But in the following years, growing distrust extended into the realm of soft power. At the end of 2024, Moscow withheld the results of an investigation into an AZAL passenger plane crash, sparking strong resentment in Baku.

Then, in June this year, relations cooled further when Russian special forces killed two brothers from the Safarov family during a raid on Azerbaijani migrants in Yekaterinburg.

Azerbaijan’s response was tough: one of Russia’s key outlets in the country, Sputnik Azerbaijan, was shut down immediately, several of its employees were detained, and all joint cultural events with Russia were postponed until the end of the year. In effect, one of Moscow’s main channels of influence through the media was cut off.

Russia’s soft power in Azerbaijan