Navigating the Middle: Georgia's strategic position in the Middle Corridor among EU and China

Georgia and China strategic partnership

Authors:

Nina Kheladze, Tbiisi

Natali Nemsadze, Tbilisi

In recent months, there have been two important developments along the “Middle Corridor” – an EU-China trade route that runs through Central Asia and the Caucasus, bypassing Russia. In Georgia, the controversial Anaklia deep-sea port project was finally awarded to a Chinese-led consortium. In Central Asia, an agreement was signed between the leaders of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China, on a long-awaited railway linking Western China with Uzbekistan. In both cases, developments have led to renewed hopes for the Middle Corridor, but also growing concerns about deepening links with China.

A port project mired in controversy

This is the site of the Anaklia deep sea port project – an empty stretch of sand along the Georgian Black Sea coast. The port lies just a stone’s throw from Abkhazia, a Russian-backed de facto state that nearly all countries of the United Nations consider to be part of Georgia.

If not for the push and pull of geopolitics and the chaos of domestic politics, there would already be a port here and Anaklia would be an important trade hub on what is known as the Middle Corridor.

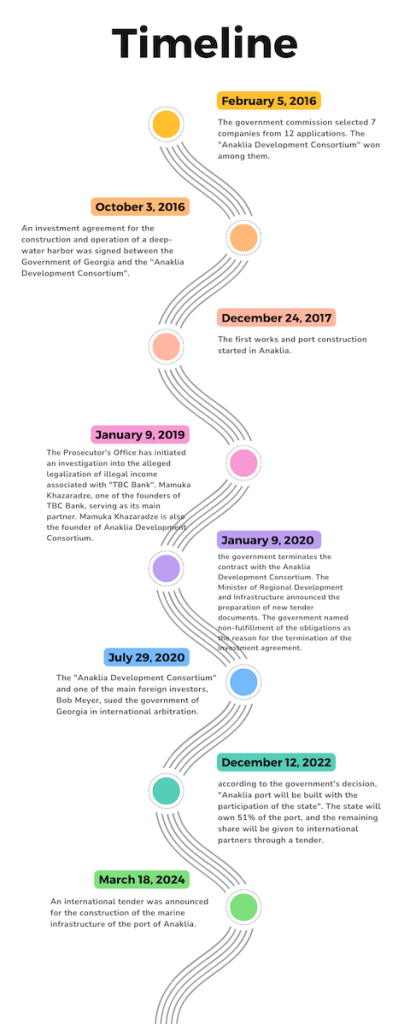

The Anaklia project dates back to 2014 under the Georgian Dream government. It was initially contracted to a consortium formed between Georgia’s TBC Bank and U.S.-based Conti International Anaklia Development Consortium (ADC), but the project was canceled amid a political controversy that saw the Georgian investors eventually facing money laundering charges.

Then, in 2022, the government re-announced plans for the construction of the Anaklia port.

There is still an ongoing arbitration dispute between the Georgian government and the previous investors but a new Chinese consortium has now been selected to complete their work.

The announcement came the day after the President’s veto on the highly controversial “foreign agent” law was overridden.

On May 29th, Minister of Economy Levan Davitashvili declared that a consortium formed of Chinese state-owned giant China Communications Construction Company Ltd. (CCCC) & China Harbor Investment Pte. Ltd, based in Singapore, would build Anaklia port, with work contracted to two state-owned Chinese companies: China Road and Bridge Corporation and Qingdao Port International Co., Ltd.

The choice of CCCC is controversial in Georgia, not in the least because CCCC is on the US Commerce Department’s “Entity List,” because of its role in building artificial islands in the South China Sea.

A Swiss-Luxembourg consortium also made an initial bid, but only the Chinese consortium submitted a final application.

The decision has led to fresh hopes that this Middle Corridor hub will finally be built, but also to new concerns about China’s growing involvement in Georgia.

A railway project at the other end of the Middle Corridor

Much further East, on the other side of the Eurasian continent, another important, Chinese-driven infrastructure project is also taking shape.

Just a week after the Georgian Economy Minister’s announcement of Chinese involvement in Anaklia, a new cooperation agreement was signed for the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway project (CKU railway). The railway will span 523 kilometers, connecting Western China with Uzbekistan through Kyrgyzstan.

This project has been “under discussion” for about 30 years, but along with Anaklia, it appears now to finally be moving forward. Over the past year, several high-level declarations have been made in support of the project, the latest being a virtual signing ceremony between the heads of state of Uzbekistan, Kyrgyzstan, and China.

This year there has finally been some progress on answering persistent questions about how the multi-billion dollar project will be funded. China has reportedly committed to a $2.35 billion low-interest loan that would cover half the project. However, details on full funding for the railway remain unclear.

According to Bakhtiyor Ergashev, research coordinator at the Tashkent-based Center for Economic Research, the railway is a welcome development, as it “would provide a cheaper option for accessing the vast Chinese market and sea ports, reducing the need to route through Russia or maritime paths through North Korea and the South China Sea.”

China and the EU’s growing interest in the Middle Corridor

According to Economy Minister Levan Davitashvili, “Anaklia port is an important project aimed at increasing the competitiveness of the middle corridor as a whole.”

The Middle Corridor, also known as the ‘Trans-Caspian International Transport Route,’ is a route for China-Europe trade. Instead of passing through Russia, along the North Corridor, the Middle Corridor traffic transits Kazakhstan, crosses the Caspian Sea into Azerbaijan, and travels through Georgia, entering the EU market via three branches: Ukraine, Turkey, or Romania-Bulgaria.

The full-scale invasion of Ukraine by Russia and subsequent sanctions against Russia have made providing an alternative to bypassing Russian territory more of a priority for both China and the EU.

According to Bakhtiyor Ergashev, “China is interested in maintaining trade volumes with the European Union, which means the Middle Corridor is essential – therefore work on the CKU railway corridor has been intensified.”

In reference to Anaklia, the Chinese ambassador to Georgia himself, points out that “the Middle Corridor is important for China-Europe logistics because we have no other choice but the Northern Line”.

At the first Investors Forum for EU-Central Asia Transport Connectivity, held in January 2024, the European Commission Vice President Valdis Dombrovskis announced that European and international financial institutions present at the Forum would commit €10 billion in support and investments towards sustainable transport connectivity in Central Asia. The ambition stated was to transform the Trans-Caspian Transport Corridor into a cutting-edge, multimodal, and efficient route, connecting Europe and Central Asia within 15 days.

However, in both the case of the CKU and Anaklia, China appears to be the driving force in building connectivity. Georgia’s decision to award Anaklia to a Chinese company will come as a blow to the EU’s Middle Corridor ambitions. Speaking to RFE/RL, Romana Vlahutin, former EU Special Representative, said: “If [Brussels] is seriously interested in the Middle Corridor, they won’t be able to do it without Anaklia.”

An infrastructure deficit along the Middle Corridor

In 2022, traffic along the Middle Corridor spiked, although it fell again in 2023. According to a 2023 report from the World Bank, the volume of cargo transported through the Middle Corridor increased by 33% in 2022, but it decreased by 37% over the first eight months of 2023 compared to the same period in 2022.

Still, the World Bank report is optimistic about the potential of the Middle Corridor. By 2030, the report claims, the amount of cargo passing through the Caspian Sea could exceed 11 million tons by 2030, almost twice its current 5.8 million tonnes of traffic. The President of Kazakhstan sounds an even more optimistic note. According to him, there is a potential for a 5-fold increase in cargo transportation in the “Middle Corridor”.

However, for this to happen, the Middle Corridor needs an upgrade.The World Bank report states that increasing volumes are conditional on infrastructure projects being implemented. – otherwise transportation demand will be 35 percent lower than the 11 million ton projection.

This decrease of traffic in 2023 is explained by operational problems and high prices. The head of the Transport Corridors Research Center, Paata Tsagareishvili, says that with the middle corridor unable to meet demand in 2023, cargo was again transferred to the northern corridor: “It partially returned to the northern corridor. According to the data from 2023, the flow in the direction of the northern corridor increased by 44 percent.”

The technical gaps in the middle corridor are also mentioned in the World Bank report. These gaps include a lack of ships, unstable prices, unpredictable schedules, and the low quality of logistics centers.

Tsagareishvili emphasizes that key connecting systems, such as Georgia’s railways and harbors, are not adequately integrated. According to the Transport Corridor Research Center, a potential opportunity to attract 10-12 million tons of cargo emerged after the war in Ukraine, but “contrary to our expectations, we did not witness the anticipated development of the corridor.”

China’s growing footprint in Georgia and Uzbekistan

With the Anaklia project now tendered, and the CKU railway moving forward, there are renewed hopes that infrastructure along the Middle Corridor will finally be developed.

However, some in Georgia and Uzbekistan are concerned about the implications of heavy Chinese involvement.

The government’s interest in a Chinese investor for Anaklia is part of a wider pattern of flirtation with the East Asian super power.

In July last year, the Georgian government signed a strategic partnership with China, upgrading Georgia’s status within Beijing’s diplomatic hierarchy. Analysts consider this move an alarming change in Georgia’s foreign policy course, especially considering China’s close support of Russia, a country that most Georgians consider an occupying force.

Tinatin Khidasheli, former minister for defense and chair of Civic Idea, claims that the strategic partnership signed by Georgia with China is part of Georgian Dream’s attempts to geopolitically blackmail the West. According to Khidasheli, by deepening relations with China, the government is saying “if [the EU] refuses us, there is always an alternative in the form of China”.

Amid the Georgian government’s growing interest in cooperation with China, Georgian experts are voicing concerns about the risks of allowing China to construct strategic infrastructure. According to Paata Tsagareishvili, China wants to “create infrastructure, load its ships, and take over the collection and distribution point.”

The choice of CCCC is also controversial, not in the least because the company is on the US Commerce Department’s “Entity List” due to its role in building artificial islands in the South China Sea.

CRBC, which is CCCC’s subsidiary and the company lined up as a contractor for Anaklia port, has also been warned in the past by the Georgian government about compliance with safety norms.

The Ministry of Economy has pushed back against concerns about sanctions. In a statement released May 30, the Ministry stated: “Neither international nor US sanctions apply to the Chinese-Singaporean consortium. This campaign is fully politicized and aims to deliberately hinder the implementation of the Anaklia port project.”

In the case of the CKU railway, there are also concerns that the project will sink the Central Asian countries involved even deeper into debt to China. According to Bakhtiyor Ergashev, “China is the largest creditor to Uzbekistan, with over $7 billion in external debt owed to Chinese banks. Both [Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan] are, in effect, held hostage by serious debts to China.”

However, Ergashev continues to note that the benefits and transit fees would be considerable – “The railway would provide a cheaper option for accessing the vast Chinese market and sea ports, reducing the need to route through Russia or maritime paths through North Korea and the South China Sea,” he says.

Whether or not the benefits outweigh the risks of cooperation with China, in both cases, Chinese engagement appears to have be the only path forward. In the case of Anaklia, the Swiss consortium failed to submit a final bid, whereas with the China-Kyrgyzstan-Uzbekistan railway, a European alternative was never on the table.

This article was published as part of the Spheres of Influence Uncovered project, implemented by n-ost.

n-ost