Thirty years later: the Lata tragedy

Lata tragedy thirty years on

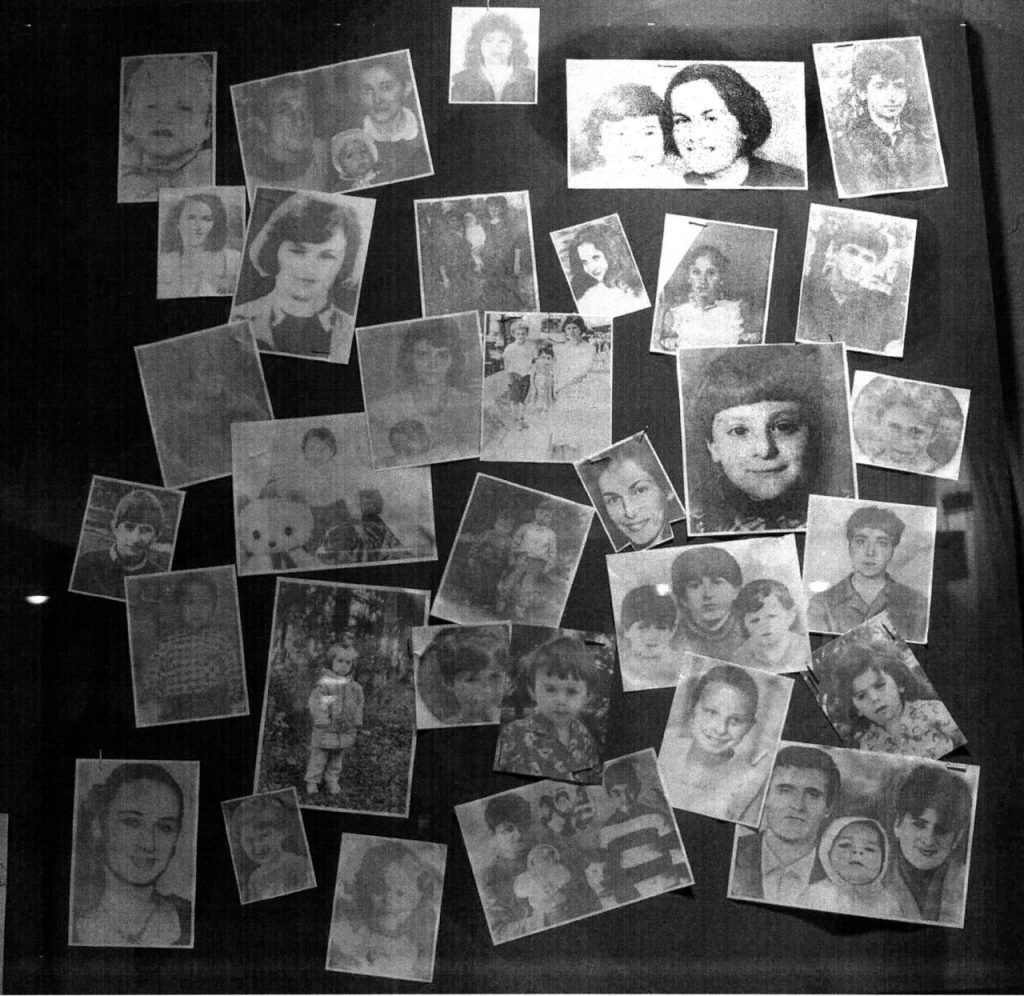

December 14 marks thirty years since the Lata tragedy occurred during the Georgian-Abkhaz war of 1992-93, when a Russian MI-8 helicopter was shot down in the course of transporting women and children from the Abkhaz city of Tkuarchal to Gudauta.

The Abkhaz and Russian sides blamed the attack on the helicopter on Georgia; Georgia in turn denied the accusations and stated that Russian manipulation was the cause of the tragedy.

There were 87 people on board the helicopter, 35 of whom were children and eight pregnant women. All passengers and crew members were killed.

These are stories of those who survived the Lata tragedy.

Arif Adzinba: personal story

Arifa Adzinba was three years old during the war. She was the eldest sister of her family; her middle brother was two years old at that time, and the youngest was born during the war. Her family lived in the village of Dzhgerda.

- Dual citizenship in Abkhazia: not a luxury, but a means of transportation

- August, 2008. Chronology of the war over South Ossetia in facts and photos

- Separated by the dividing line: My father will never leave Abkhazia. Video blog

“Our village was shelled because there was a hospital and a garage where tanks were repaired. So my father, his brother and second cousin decided to send women and children to Gudauta where it was safe.

And so we – three families from the same clan – went to Tkuarchal. Our uncle brought us. We stayed with our grandmother’s sister. Then my uncle arranged to take us to Gudauta, but when we got into the car to go to the helipad, the car simply wouldn’t start. No matter how much my uncle tried to start it, it just wouldn’t start,” Arifa says.

“Before they could get on the helicopter, the family returned to our grandmother’s sister’s apartment. And soon someone knocked on the door. Her brother asked: “Where are those who came with you? Where are they?”

Arifa says that many simply did not know for sure whether their relatives and friends had gotten into the helicopter or not: “At first, they didn’t know anything. And the next day in the garage, the radio was broadcasting the news. It was there that my father heard that the helicopter had been blown up.”

Esma Pilia

Esma Pilia encountered the war in Akuaska, her father’s ancestral village, where her family often spent their summer holidays. In August 1992 Esma’s mother, along with her youngest son, went to vacation in Kislovodsk. Her father, a deputy of the Supreme Council, left for Sukhum. Esma was left their with cousin Naala to look after her.

“I remember that it was very scary in Tkuarchal. I was terribly afraid of shelling, but did not dare to tell my dad about it.

It was very difficult to get into the helicopters carrying out humanitarian flights – the lists were compiled in advance, it was physically difficult to get through the crowd to the doors. People never knew if a helicopter would come that day. On December 14, 1992, it should have worked out.

“That day my parents were going to the village, and we had to fly away. But I got stuck. She said that I would not fly anywhere and also wanted to go to the village. Naala said that without me she would definitely not fly away. So the day passed – we went to the village and returned, and Naala was in Tkuarchal,” recalls Esma.

“In the evening, guys from the headquarters began to come to us and ask where we were. We said here we are, at home. They did not believe us and asked again, although we were standing in front of them. We couldn’t understand what had happened, and only at night a neighbor said the Georgians had blown up the helicopter,” she says.

“There were screams from every house. I will never forget them. The whole city was screaming. The man who sent away his wife and three children, including a newborn, was just walking around the city lost. It was terrible.

I adored my hometown Tkuarchal. But when the helicopter was shot down, it seemed to me that I would die in this city, that it did not want to let me out. I hated Tkuarchal so much that after the war I was not there for fifteen years. And now, only now, when I’m well over 40, I go there with pleasure. The fear that settled in me then, at the age of 14, it is over only now,” Esma says.

On January 11, 1993, the Pilia family managed to leave Tkuarchal and fly to the North Caucasus.

Runaway child

When the war began, Temur Dzhapua was a graduate student at the Institute of World Literature in Moscow. On August 14, 1992, he was supposed to fly home for the holidays. His son, 11-year-old Gudisa, had been in Abkhazia since the beginning of summer, in the village of Chlou.

The flight on which Temur was supposed to fly home was delayed, and he was told that “in fact, a war broke out at your home.” Temur went to Abkhazia by land and he got there within a week; eventually he got to the front.

On December 14, Temur Dzhopua brought his son and a four-year-old neighbor to Tkuarchal. There were no agreements that the children would be taken, but they still found a place on board.

“The children said they would not fly without me. I told them: “Okay, you are small, first they will put you in, then I will sit down too.” Naturally, I did not plan to sit down. I persuaded them, we put them in the helicopter.

But at the last moment, when the doors were already closing, the neighbor’s kid suddenly saw that I was staying outside.

They jumped out of the helicopter, the blades were spinning. They were so small, it was hard to catch them. They jumped over and ran away from the airfield. I couldn’t send my son alone. I got my son out of the helicopter.”

Temur and his son stayed in Tkuarchal. The next morning, they got ready to go home early to report that the children had not flown anywhere and were alive; unlike 35 other children.

“I knew a lot of people who got on that helicopter. There were people from my village. When we were driving home from Tkuarchal, we were met on the way by our neighbor, a grandfather on a tractor. He stopped me and asked if I saw his family, if they had gotten onto the helicopter. And I saw and knew for sure that they landed and flew away. But I couldn’t admit it to him.”

Terms, place names, opinions and ideas suggested by the author of the publication are her / his own and do not necessarily coincide with the opinions and ideas of JAMnews or its individual employees. JAMnews reserves the right to remove comments on posts that are deemed offensive, threatening, violent or otherwise ethically unacceptable.

Lata tragedy thirty years on