"We share weddings and funerals." Stories from a village in Georgia where Armenians and Azerbaijanis live side by side

Armenian and Azerbaijani villages in Georgia

Last year, in late 2023, the protracted conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, which spanned decades, finally reached its resolution.

Armenians and Azerbaijanis represent the two largest ethnic communities residing in Georgia, following the Georgians themselves. As per the 2014 census data, Azerbaijanis constitute 6.2 percent of Georgia’s populace, while Armenians account for 4.55 percent.

These communities predominantly inhabit two distinct regions within Georgia: Armenians primarily reside in Samtskhe-Javakheti, whereas Azerbaijanis are concentrated in Kvemo Kartli. However, there are districts and villages within Kvemo Kartli where these two ethnic groups coexist, living in mixed communities.

- Baku has won, Armenians are leaving NK: Opinions of all sides of the conflict

- Pashinyan proposes to establish arms control. Will Baku agree?

The Karabakh conflict has consistently influenced the lives of both Armenians and Azerbaijanis. Throughout history, sporadic ethnic-based tensions between these two communities in Georgia have been recorded, ranging from protests to expressions of support for either Armenia or Azerbaijan.

Social media platforms often served as arenas for contentious debates. Discussions pertaining to the conflict frequently spiraled into heated arguments, marked by derogatory remarks and an inundation of xenophobic sentiments from various quarters.

In an effort to gauge the impact of recent developments in Karabakh on the relations between Azerbaijanis and Armenians residing in Georgia, JAMnews undertook visits to several villages in Kvemo Kartli.

The Karabakh conflict, a protracted conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan, commenced in the 1990s. The confrontations unfolded within the territory of Nagorno-Karabakh, a former autonomous region of Azerbaijan, along with adjacent territories. In April 2016, the region witnessed the onset of significant hostilities, known as the “April War” or the “four-day war,” which endured for four days.

In the summer of 2020, tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan once again reached a critical juncture. By the autumn of that year, these tensions escalated into a full-scale war. The conflict persisted for 44 days and was subsequently dubbed the Second Karabakh War. Eventually, a ceasefire was brokered, stipulating that Azerbaijan would regain control over several districts of Nagorno-Karabakh, with Russian peacekeepers deployed to the region to maintain stability.

In September 2023, Azerbaijan declared the commencement of an “anti-terrorist operation” in Karabakh, with the objective of “restoring constitutional order” in the region. Despite this announcement, Armenia’s Defense Ministry, Foreign Ministry, and Prime Minister’s Office maintained a resolute silence. It soon became apparent that the fall of Karabakh was imminent, with the outcome expected within hours or days.

As anticipated, the operation concluded within a mere two days, ushering in a new reality for Karabakh. Consequently, on January 1, 2024, the unrecognized entity of Nagorno-Karabakh officially ceased to exist.

“We have been living and working here together for so many years” – Shulaveri village where Armenians and Azerbaijanis live together

There are only a handful of villages in Kvemo Kartli where Armenians and Azerbaijanis reside together. Among them are Shulaveri, Khojoni, and Tsopi. Our visit took us to Shulaveri.

Shulaveri, situated 54 kilometers from Tbilisi, comprises nine villages.

At the end of January, the cold weather prevails. The journey from Tbilisi to Marneuli is characterized by icy roads, interspersed with patches of snow.

Similarly, in Shulaveri, frostiness envelops the atmosphere. In the village center, contrasting with its surroundings, an old white minibus serves as a makeshift stall for selling tangerines and oranges. However, there are few buyers in sight; those who do appear often head straight to nearby supermarkets.

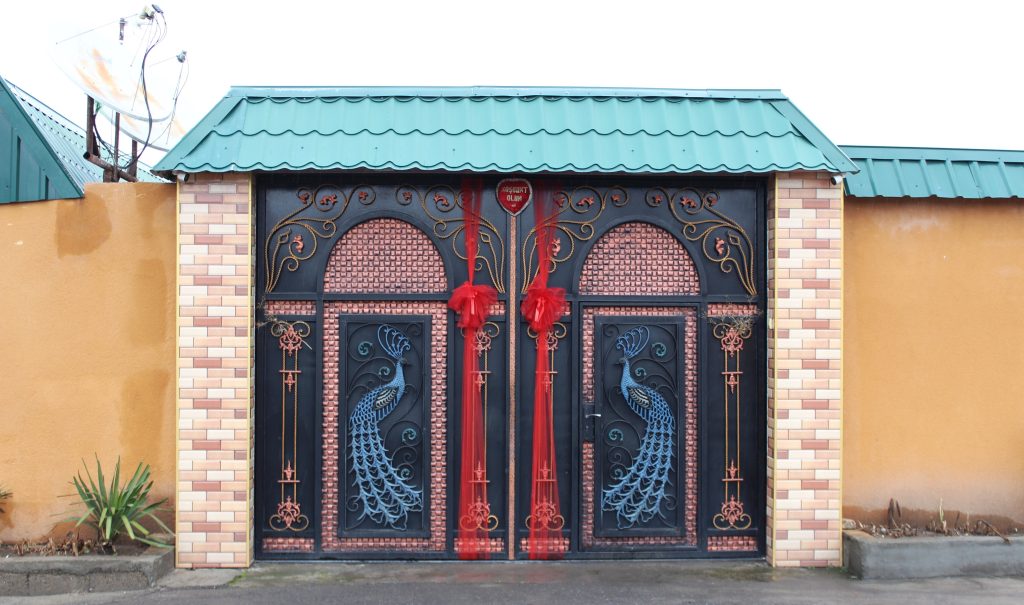

“Rio” and “Bmart” stand prominently, distinguishable from afar by their imposing presence. The resemblance in shape, color, and façades of these two enormous food markets is striking. While Bmart is owned by an Azerbaijani proprietor, Rio is owned by an Armenian. Despite their ethnic differences, both Armenians and Azerbaijanis collaborate harmoniously within these establishments.

In the vicinity, a bit further down the road within the same building, one can find an Armenian butcher shop alongside an Azerbaijani store specializing in car parts.

Shulaveri is a sizable village, bustling with activity and opportunities for employment. Consequently, individuals from neighboring villages, including Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Georgians, flock here in search of work.

Angela Veronyan, aged 44, hails from Imir village, predominantly populated by Armenians. For the past nine years, Angela has been employed at the Rio market in Shulaveri village.

At the age of 17, Angela, who was raised in Imir village, entered into marriage without prior knowledge of her future husband. She vividly recalls the day when his family approached hers to propose the union. Given their families’ acquaintance, the decision was made without Angela expressing any preferences.

Reflecting on that era, she reminisces, “It was a different time back then. I never imagined marrying someone I didn’t know. There was no internet or telephone to facilitate communication.”

Angela lived with her husband for a period until tragedy struck in 2003, when he passed away in an accident, leaving her, at the age of 24, to raise their two children alone. In the subsequent years, she intermittently traveled to Russia for employment. Initially employed as a cook, she later worked as a confectioner at a marmalade factory.

When circumstances became challenging, Angela returned to Georgia and sought work. She initially found employment at a rural pharmacy before eventually securing a position at the Rio market.

Angela remarks that the recent events in Karabakh have particularly impacted the younger generation, igniting fervent discussions. However, she recalls no instances of conflict in either her village or Shulaveri.

“We’ve been living and working together for so long that we don’t even bother distinguishing between Armenian and Azerbaijani. We share a lot in common,” Angela explains.

The story of friendship between Susana from Armenia, Ganira from Azerbaijan and Marina from Georgia

On a crisp January morning, the comforting ambiance of the Sahakyan family’s snug abode feels like a slice of paradise.

In the kitchen, Susana Sahakyan expertly prepares tolma wrapped in grape leaves, anticipating the evening’s hospitable gathering of guests.

Among the honored guests for the evening is Susana’s friend and neighbor, Ganira. But before the festivities commence, Susana and Ganira sit down over coffee, reminiscing about their youth.

Susana Sahakyan was born in the Armenian village of Damia and entered into marriage at the tender age of 17. This union placed her in a community where Armenians, Azerbaijanis, and Russians coexisted. Half a century ago, during Susana’s early years in Shulaveri, the village boasted a significant Russian population.

In Shulaveri, Susana raised three children without pursuing employment outside the home. Following the completion of eighth grade, she forewent further formal education to focus on her familial duties.

“My husband has always been a hard worker,” Susana shares with a laugh. “In the past, there were factories here. Nowadays, he’s taken up music and does what he can.”

Initially fluent only in Armenian, Susana has since learned Azerbaijani and Russian languages.

It was in this village that she met Ganira.

Ganira Osmanova was born in the Azerbaijani village of Baitalo. Her father worked at a factory in Shulaveri, prompting the family’s relocation here.

Her journey towards a broader horizon commenced during the sixth grade. Initially, she attended school in Azerbaijan before continuing her education in a Baku school. Subsequently, she pursued further studies in Kazakhstan, where she married an Azerbaijani from Karabakh. Following their time in Kazakhstan, they resided in the Republic of Tatarstan and various regions of Russia before settling in Georgia in 2009.

“In hindsight, I should have married in Georgia and stayed put. But what can you expect from a young, impulsive girl? Youth tends to cloud judgment; you don’t ponder whether he’s the right fit or how your family life will unfold. Later, I came to regret it,” Ganira shares.

Professionally, she is a doctor. She worked as a rheumatologist in Kazakhstan and as a midwife in Georgia, though she harbors no fondness for the latter profession.

– But there’s a doctor for the entire neighborhood, someone to administer injections and such,”- Susana remarks.

– Yes, but I don’t enjoy it. I do it out of necessity for the sake of others,” Ganira responds.

Ganira and Susana’s husband grew up together as neighbors. By the time Ganira returned from Russia, Susana had already become a part of their family as a daughter-in-law.

-“I’m not sure what they think of me, but to me, they’re family,” Ganira confides.

-“Do you doubt it?” Susana’s hand, still holding the tolma, pauses mid-air.

– “And for us, Aunt Galina, and for us,” adds another voice to the conversation.

In this family, Ganira is affectionately called Galina.

“When we go away for a few days, we entrust everything to Aunt Galina. She takes care of the house and the animals,” Iveta shares.

“We also have another friend, a Georgian named Svanka. She’s like our jack-of-all-trades,” Susana chuckles.

“She’s from the village of Tsereteli. Like me, she married impulsively here. She works at the water company. I remember the first time she came. It was summer, a sunny day, she was hot and tired from checking the water meter. We offered her water, she sat down, rested, and we became friends,” Ganira recalls, adding, “Now, she calls in the evening and asks what I’m doing. Then she calls a cab and comes over.”

The Sahakyan family acknowledges that the war affects everyone, and each person holds their own opinion. However, in Georgia, neighbors find no reason to quarrel with one another.

“Our children haven’t faced any problems because we don’t segregate them. If I need something from the store, I’ll just shout in the yard, ‘Children, bring it to me!’ Those who understand will run, regardless of whether they are Georgian or Armenian,” Susana explains.

Furthermore, Susana emphasizes that nobody celebrates the victory or defeat of any side. Instead, they collectively mourn the loss of lives on both sides.

“Just recently, the 18-year-old grandson of our Armenian neighbor died in the war. His girlfriend, who is married in Armenia, watched as he served in the army for two months before going to war. We all cried together, the neighbors. It’s heartbreaking that an 18-year-old lost his life—such a tragedy,” Susana expresses with sadness.

Ganira recounts an experience of sheltering an Armenian family in her home in Baku during the initial war.

“They know. I was residing in Baku at the time, having recently purchased an apartment. We had one Armenian neighbor, who served as the head of the station. However, he was away on duty when the conflict erupted, leaving his wife and children stranded. With gunfire echoing from all directions, I hardly knew this family, yet I harbored them in my house for 15 days, barring other neighbors from knowing. Eventually, they clandestinely departed,” Ganira narrates.

She maintained communication with them for a while. However, when it became perilous to converse over the phone, they ceased all contact.

“I came straight from Spain to Shulaveri. That’s how love works.”

“I’m originally from Tbilisi, born and raised there, then I moved to Europe. I met my husband on the Internet and came straight here to Shulaveri,” Iveta Markosyan, 45, the daughter-in-law of the Sahakyans, humorously summarizes her story in two sentences.

Iveta is an Armenian woman originally from Tbilisi. She was around 24 years old when her mother was diagnosed with cancer. During that time, the state lacked sufficient resources to support such patients.

The family liquidated their assets, but it did not yield the desired results. In the early 2000s, Iveta’s parents sought medical treatment in France.

Gradually, over time, all family members relocated to France, where her mother’s health significantly improved.

They never contemplated returning to Georgia.

“I’m very happy to live here,” says Iveta, who met her husband on the internet while residing in Spain herself.

She moved directly to Shulaveri to settle in Georgia. The girl, who was raised in Avlabari, had never had Azerbaijani neighbors before. Therefore, the mixed environment felt somewhat unfamiliar to her.

On the same street where Iveta’s family resides, Armenians and Azerbaijanis coexist. Iveta no longer concerns herself with distinguishing between Armenian and Azerbaijani families.

From being a teacher to becoming a cab driver, along with Ukrainian spouse and Armenian acquaintances.

Elshad Aliyev, aged 55, resides in Dashtaf, a village near Marneuli predominantly populated by Azerbaijanis.

Elshad works as a cab driver, with the bulk of his clientele coming from Shulaveri, where he spends most of his days. The distance from his village to Shulaveri is approximately three kilometers, a 5-10 minute drive.

Elshad and his family have formed close bonds with many Armenian friends, particularly with children attending the Russian-speaking public school in Shulaveri.

“We live harmoniously and cordially; there’s nothing to divide us. Even during times of unrest in the past, we maintained our friendly relations,” Elshad remarks.

In the quiet of the morning, as his first customers have yet to arrive, Elshad shares with me the story of his past, recounting his time in Ukraine many years ago and how he fell in love with a young Ukrainian woman.

After completing his schooling, Elshad began his career as a physical education teacher at the local village school. Shortly thereafter, he was conscripted into the Soviet army and found himself stationed in Ukraine.

During his time in Ukraine, Elshad crossed paths with a Ukrainian girl and began corresponding with her. Meanwhile, upon being demobilized, he secured employment as a driver for a local deputy in the city of Sumy.

By then, Elshad had already fallen deeply in love.

“It was fate that brought us together; we exchanged letters throughout our time in the army,” he chuckles when I inquire about how he managed to win over a Ukrainian girl to the extent that he brought her to Georgia.

Elshad and Lyudmila had two grand weddings. The first took place in Ukraine, followed by another celebration in Georgia. At that time, Elshad was 23 years old, and Lyudmila was 16.

It was during the 1990s when job opportunities in Georgia became scarce. Despite this, Elshad chose to remain in Georgia to support his father.

This year, Elshad and Lyudmila will commemorate their 25th wedding anniversary on October 19. Elshad always remembers this day. Although the celebration might not be as extravagant as before, it will be a small family gathering where everyone, including their Armenian, Azerbaijani, and Georgian neighbors, will be invited.

A new beauty salon and an old photo studio share a building

From afar, the old “FOTO” sign and the new “IBO BARBER” sign, both in large letters, are visible on the facade. This building houses both a photo studio and a beauty salon.

The photo studio appears aged, with yellowed walls, while the salon boasts a fresh renovation and a brick facade.

Roman Kalandarov, 40, opened this salon for men in Shulaveri two years ago.

“No one here distinguishes anyone by nationality, why should we choose our clients,” he tells me, adding that he has more Armenian friends than Azeri friends.

Farman Sharipov is a photographer from Shulaveri. His old atelier is filled with cameras, televisions and a thousand other devices. On a small shelf stand the flags of Georgia and Azerbaijan.

A green comb hangs beside a gold-framed mirror, showing signs of tarnish from time. The comb itself is also old.

Farman’s is primarily frequented by individuals needing passport, visa, or other document photographs taken.

“This morning I earned six GEL [about $2.25], and I spent 10 GEL [about $3.7] on gasoline and 10 GEL on cigarettes. But I enjoy it; it’s my hobby, so I’m not going to give it up,” Farman explains.

In his youth, he used to photograph many Armenian weddings.

However, he no longer does so; instead, he is invited as a guest. For instance, at the end of January, he was invited to the wedding of the school principal’s son in the village of Tsitelsopeli. The wedding will be Armenian.

“When I enter an Armenian village and raise my hand to greet, and I walk through the whole village with my hand raised, everyone greets me. Everyone loves me, and they don’t let me leave without having coffee with every family,” Farman says.

“There may be more conflict among younger people, but older people perceive things differently.”

Garik Gasparyan hails from the village of Tsitelsopeli, an Armenian settlement situated adjacent to the Azerbaijani village of Dashtaf and the Georgian village of Maradisi.

Garik maintains friendships across different nationalities:

“About 80 percent of my friends are Azeris. We communicate in Georgian and maintain friendships with everyone.”

A student at Tbilisi State University, Garik has been actively involved since his high school years. He engages in numerous projects and frequently leads training sessions for his peers, providing him with a keen understanding of the sentiments among young people.

“Sometimes there are minor conflicts among young people. There are some who, following this war, have developed a somewhat superior attitude. They [Azerbaijanis] may say, ‘Look, our country emerged victorious.’ However, they are in the minority. Generally, the situation hasn’t changed much,” he explained.

Garik notes that residents of mixed villages tend to be more amicable towards each other due to their longstanding coexistence. This sentiment extends to the older generation as well.

“Here, people attend weddings and funerals together, exchange holiday greetings, and generally maintain harmonious relations. No one desires discord. For instance, there’s a Russian school in Shulaveri, where children of all ethnicities study together,” Garik adds.

“I’m not surprised that these people live together. We’ve always had a very good thing going.” – Georgian pharmacy in Shulaveri

Naira Talakhadze, 61, has been working as a pharmacist in Shulaveri for several years and is well-versed in all the news of the village:

“People from all ethnic backgrounds come here, engaging in diverse discussions on a multitude of topics. Even discussions about the news from Karabakh occur without hostility. They understand each other’s languages.”

Originally from the village of Saimerlo, which was established in 1951-1952 to accommodate people relocated from Imereti to the Azerbaijani and Armenian-populated region, enabling the establishment of Georgian settlements.

“I’m not surprised by the coexistence of these people because Armenians, Azerbaijanis, Kurds, and Isorians have been coexisting harmoniously since ancient times. Wars and conflicts haven’t disrupted this region. Everyone agrees that we live together here, contentedly. What happens elsewhere doesn’t concern us; we’ve been together and should remain together,” Naira Talakhadze explains.

Armenian and Azerbaijani villages in Georgia