The Eurasian Georgia?

What’s next for Georgia? Ghia Nodia

On the evening of October 26, when the chairman of Georgia’s Central Election Commission announced the official results of the Parliamentary elections, he thus probably signaled the end of a specific stage of our history. It started approximately at the end of the 1990s or with the Rose Revolution, and its substance was advancing towards Europe.

We were not fully European in our social and political practices, but we recognized European ideas as our own and bit by bit approximated them, or tried to. Conversely, Europe gradually came to recognize us as part of itself.

Now we are moving to a qualitatively different condition, which I will call a Eurasian Georgia.

I have to make a caveat here: Like many others, I don’t believe that the election result reflected the will of the Georgian people. There will and should be protests and different forms of resistance, but they may not prove sufficient to induce the government to make principal concessions. Hence, here, I will start by saying that however unfair the official election results might be, they will stay.

If this is so, questions naturally emerge. How did we come here? What should we expect now? I will share a couple of considerations.

Why did we lose? A geopolitical aspect

The massive use of illegal methods by the government does not explain everything. Even in central areas of Tbilisi where the opposition scored its best, the Georgian Dream still (GD) got about 40 percent of the vote. That’s very much. It’s logical to presume that in other areas its genuine support was higher. Why?

First of all, the main message of the GD, “We chose peace”, proved quite effective. Yes, all their talk of the Global War War party constitutes a paranoid delusion, while banners depicting a contrast between a war-ravaged Ukraine and a flourishing Georgia were utterly immoral. But at the end of the day, this activated the most basic human instinct – the fear of war.

How could the opposition confront this? It decided not to be drawn into this debate but change the subject instead: the elections had to be about a choice between Europe and Russia. This rightly depicted what was at stake. But how successful was this as a pre-election strategy?

On the face of it, it had to be: We know that the large majority of Georgians prefer Europe to Russia. But the GD succeeded in planting an assumption in the minds of many (without actually spelling it out) that at the moment, the move to Europe implies a war with Russia, or at least a significant risk of it. It is not surprising if the fear of war beats the attraction of Europe.

Now, some reproach the opposition for not engaging in the challenge of the “war vs peace” debate. This may be a fair critique. But it did so because it did not have a simple answer to the government’s rhetorical question: “Do you want a war, then?” Such an answer had to also account for the reality that Russia was truly punishing Ukraine for its pro-western policies, as it did attack us for the same thing in 2008. The best the opposition came up with was saying that “the isolation is bad” – fair enough, but it didn’t impress enough.

I am far from suggesting that the GD thinking was right; but in a pre-election campaign, you need clear and simple messages rather than complex geopolitical analysis. The opposition critics should have suggested better versions of such messages. – which I never heard.

The election result should be seen in the context of regional geopolitical conflagrations. One of the reasons for our defeat was that, at the same time, Russia was on the offensive in Ukraine. It implied that the West was retreating as well. From the very first days of the war, Ivanishvili put his stakes on Russia’s victory; as much as I may hate saying this, at this stage this proved expedient for him. Had the war gone in favour of Ukraine, our election result might have been different as well.

Civil society against the administrative resource

All elections in Georgia imply a fight between the administrative resource and the civil society (understood broadly as public-minded people capable of self-organization). This fight is extremely uneven, as the resources of civil society are meager compared to those of the state.

Criticizing the opposition will become popular again. Some of it will be fair. However, I doubt we could have had a much stronger opposition at this point. A powerful opposition is based on a robust civil society, ultimately – on the strong middle class. We don’t have that yet.

The government, on the other hand, has a well-oiled machine of the state that it got as a legacy from the United National Movement government. It further increased its capacity to control and repress the society.

We know from our history that the opposition can still win elections if societal discontent reaches a critical point and if there are discords within the ruling elite. This was not the case this time.

The state of the economy was conducive to this. We cannot deem the welfare of our citizens satisfactory, but the economic dynamics of the last years were fairly positive, also because, in the short term, Georgia benefitted from the stand it took towards the war. The high inflation of 2022 was largely forgotten. Bread and butter issues that most people are concerned with did not play a big role in these elections; it’s hard to win without appealing to them.

What should we do in Eurasian Georgia?

The official election results turn us into a Eurasian country instead of a European one.

Why do I say “Eurasian” rather than “Russian”? Using the latter word would not be a mistake: Indeed, this election result made it final that in a conflict between Russia and the West, we are on Russia’s side (even though we don’t say this openly). But this does not yet imply that we are openly moving towards Russia. The latter has won because Georgia has effectively given up on its European aspiration. The rest is details.

I want to say that typologically, we are becoming a Eurasian country (which does not necessarily mean formal membership in the Eurasian Union). Such a country might not have a clear-cut foreign political course at all. Anti-western narratives and actions do not preclude transactional deals with the West on specific issues – if the latter agrees. This is what Bidzina Ivanishvili, the GD leader, calls “regulating relations” with the West.

The greatest benefit Ivanishvili derives from moving to the Eurasian camp is that it now can effectively ignore the Western opinion (which he has been doing in the last years already).

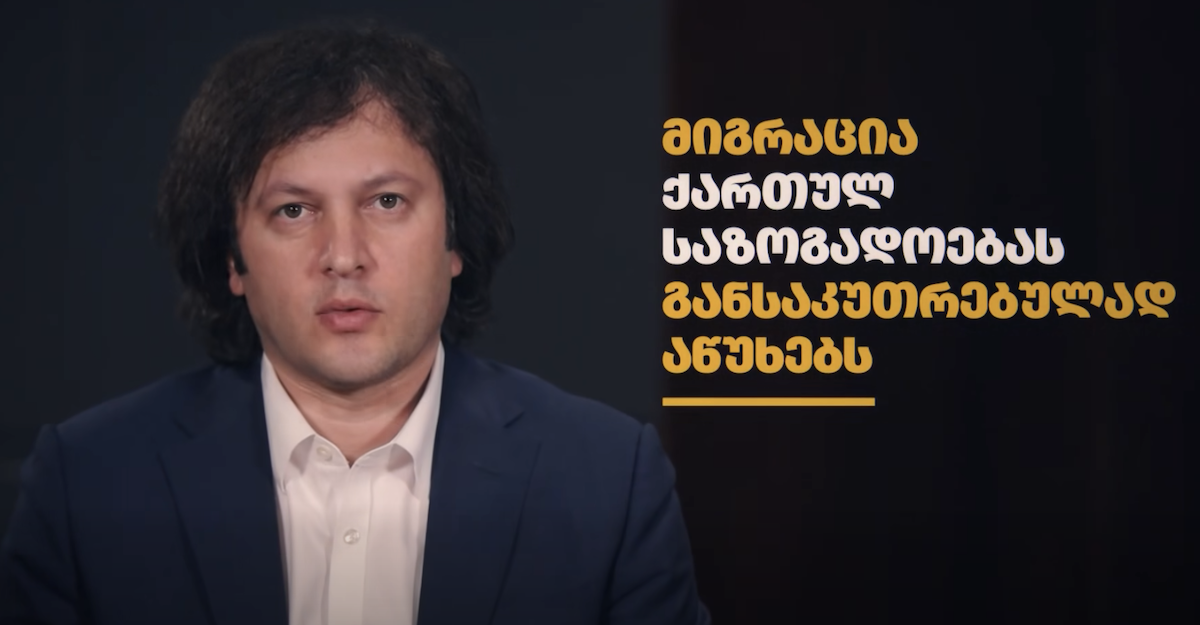

The main result will be a comprehensive offensive against institutions of civil society: the opposition parties, NGOs, independent media, and universities. This offensive is already heralded; it will probably constitute the main political content of the forthcoming years.

Ivanishvili will aim to turn Georgia into a country like Belarus or Azerbaijan. I hope it will prove difficult, but I cannot rule out him being successful in this.

If we try to define the most important thing Georgia has achieved in the last decades, it will not be the EU membership candidate status: as of today, this has zero value. The most important one was creating a real (if not singularly powerful) civil society. We got used to speaking and acting freely; it will not be easy to make us unlearn this, though Ivanishvili aims at just that.

This implies that in effect, the Georgian society moves from the offensive to a defensive stand. Today we are in a condition similar to that of the Ukrainian fighters in Donbass: we should fight fiercely to retain as much as possible, though may also retreat, in an organized manner, from certain areas. The only difference is that our means are not military.

At this point, society is confused, depressed, and, to some extent, in denial of reality. This followed an hour-and-half-long euphoria after the results of the exit polls signaling the opposition victory were announced. Staying in this stage long is very dangerous. First of all, we should regain the sense of reality. Our offensive was not successful, this round was lost. Now, we should focus on defending what we have and prepare for the new offensive when the right time comes (nobody knows when this will happen).

The role of the West in the new circumstances

In this fight, we continue to expect the Western support. However, unfortunately, we tend to overestimate its leverage and capacity in relation to Georgia.

Up to recent times, the Western leverage mostly rested on the fact that Georgia aspired to the European and Euro-Atlantic integration. The EU could reward Georgia by providing specific benefits (visa-free regime, membership candidate status, etc) or punish it by refusing to grant specific benefits. Now that the window of Western integration is closed, this leverage is gone.

We can also lose benefits we already have (canceling the visa-free travel would be especially painful), but having secured at least another four years in power, Ivanishvili’s regime will not be too deterred by this.

We also know from history that the effect of Western sanctions is limited. We could gain some satisfaction from learning that some bad guys will not be able to travel to Europe and the US, but this will scarcely change Ivanishvili’s behavior. It will be difficult to come up with sanctions that will induce him to give up power.

This doesn’t mean that he doesn’t care for Western opinion at all. He is ready to be engaged in horse trading with it. We don’t know yet how the West will react, but we cannot rule out that, as there is no longer hope of Georgia tuning around for the time being, it establishes some transactional relations with the Ivanishvili regime – but it will treat it as another Eurasian country, not as its partner.

The West will not “abandon” us, – but it will partly lose interest. This suits both Ivanishvili and Russia. Our civil society should maintain the hope for Western support but learn to depend on it less.