Stalin and the only prehistoric trilobite in Georgia

Stories about Tbilisi and Sukhumi

Vazha Kakabadze, a geologist, economist, writer and artist, regards himself as an indigenous resident of Tbilisi, though he was born in Abkhazia. But most of his memories are related to Tbilisi. And that’s what this story is about.

Many people think that this house at #95 Aghmashenebeli Avenue in Tbilisi was built at the cusp between the 19th and 20th centuries, or even earlier. It look so. But it was actually built in 1950 and has acquired its present-day appearance following the avenue reconstruction in 2011.

This house was built for the officials of the Central Committee of the Communist Party of Georgia. But in 1963, when Vazha Kakabadze’s family moved from Abkhazia, the party workers had no longer lived there.

When Vazha’s family moved from Gudauta to Tbilisi, he was in his 3rd grade. All houses were state-owned at that time and it was impossible to sell or buy an apartment. So, they swapped the apartments, which was a rather complicated process:

“Initially, there was a single, Jewish woman residing in my apartment. She wanted to move to Moscow. Whereas in Moscow there was an Abkhazian family that intended to move to Abkhazia. So, we swapped our apartments and all of us were satisfied.”

Today, 50 years after those events, there is no one left from Vazha’s former neighbors. He himself would like to move to a new place. But he can’t finally make up him mind about leaving his neighborhood, house and street, that was called ‘Plekhanov’ during his childhood.

“Our immediate neighbors were the Enukashvilis, an amazing family that worked at the Young Spectators Theatre and they often invited us to the performances. All the neighbors gathered and went to see the performance together. I watched some performances several times and I still remember nearly all mise-en-scenes.

Mass repatriation of the Soviet Jews started in the ‘70s and the Enukashvili family left for Israel. We, all the neighbors, were very upset. And they wrote later that they missed us a lot and that they were even think about buying back their former apartment – they were going to come every year and stay there. But that idea could be hardly fulfilled in the Soviet regime conditions.

This 6-storey building was designed just for 6 families. The neighbors had such close and warm relations that even some relatives could have envied them: birthdays were celebrated at home, they stayed in the yard till late hours in summer and if anyone had any problem, the neighbors were always there, ready to help.

Today, such way of life and relations between the neighbors is already a thing of past.”

“There is a niche in the arch at the house entrance. Nobody needs it nowadays. Whereas in my childhood, a watchmaker-Kurd was accommodated there. I don’t remember his name, but I still could see his face before my eyes. He was an extremely energetic man.

Then his competitor appeared on the other side of the street, and he turned out to be more successful. And ‘our’ watchmaker just started up a new business – he was refilling ink in ballpoint pens, which was a rather costly innovation at that time and this service was in high demand. At the same time, he did not charge the children from our yard the money for refilling.

I also remember another Kurd from my childhood. He was walking around with a box, selling ice-cream. His heart-rending scream ‘Ice cream!’ shook the district. I was a little boy then, and I used to approach him and put on an unhappy face. And he often gave me ice cream.

And also, there was an incredibly kind Kurd, a shoemaker named Gabo, who worked in a booth near my school. If he noticed a poor child, he would always toss him a few kopeks. There was an orphan in my class, whose last name was Kikoleishvili. His grandmother raised him. Once Gabo saw him wearing shabby shoes and he sewed him a new pair for free.”

“I was baptized by a Russian scientist, Slava Mukhin. He actually lived in Kuybishev, Russia, but he often visited Tbilisi and stayed at our place.

My parents met him when they lived in Gudauta. He and his mother came from Kuibyshev on vacation and they were looking for an apartment to rent for a couple of days. Although our family didn’t rent out rooms to visitors, but when my mother came to find out that they had nowhere to stay, she invited them to stay at our place overnight. They dined and communicated. And my parents liked them so much that the next morning they didn’t let them go.

So Slava and his mother stayed at our place for two weeks, and my mother warned them that they shouldn’t dare talk about payment. They went to the seaside together, my mother cooked delicious meals, in the evenings they would take a walk along the embankment together.

Then, one day, they suggested to baptize the children. Any links with church were not approved those days and they could pose a real risk to one’s career. My mother sent the father off to the village for a couple of days, to make things look like he was unaware of what was happening, and we, the children, were stealthily taken to church. Slava baptized me, and my sister was baptized by his mother. That’s how our families chummed up.”

(courtesy photo)

“My father’s name was Vladimir Kakabadze. He was an officer. During the WWII, he served in Keda village, Samtskhe-Javakheti, where the Soviet military base was stationed.

It was there that he met Rusudan Gagua, who was a German language teacher at the village school.”

“They got married and the war finished by that time. My father left military service and the family moved to Gudauta, Abkhazia. He was appointed for the Education Center director’s post by the party, that’s how things were done at that time. I, the 5th child, was born to them in Gudauta.

Gudauta is my homeland in every sense of this word. Our house was located at #14 Kiarazi street. When my parents moved there, there wasn’t even the water supply system. There was a wonderful Abkhazian family, Tarba, living next to us. They had a private house with a large yard and a water tap. So, we were allowed to come to their yard for water anytime. And they even removed the fence so as to shorten the distance to the water tap.

That’s how friendship between our families began. When my parents left for work, they would sent me to them, since there was always someone at home. I stayed there for days on end. I was on friendly terms with the youngest boy, whose name was Aslan.

He also had a brother, Lulu, who was much older. He was 24-25 years old then. There is a tragic story related to him, which occurred in the late ‘50s.

The matter is that close relatives of the Tarba family were forcefully displaced to Turkey in the Mohajir period, during the war with the Russian Empire, in the 19th century. This story made Lulu restless. He didn’t like the Soviet system, and he wanted to flee to Turkey, to those ancient relatives. Adults were talking about it in a whisper and I overheard it.

So, one day Lulu disappeared. Later, the family was notified that he had drowned in the sea. It turned out that Lulu had got a boat, put it out to the sea and headed for Turkey. People said that a tragedy happened because it was impossible to sail the sea on an ordinary boat. But another version that was also mentioned, that he had been caught by border guards, sounded more plausible. Moreover, the body was not handed over to the family. The family couldn’t openly mourn for their son. They were afraid of punishment. Presumably, he was shot dead.”

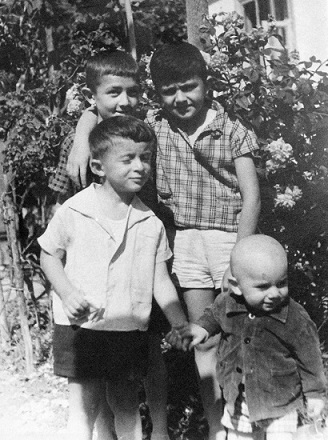

with the neighbor children

(courtesy photo)

Vazha Kakabadze’s paternal ancestors were representatives of the clergy, the natives of Kukhi village, Khoni district:

“Once my father took me to the village, to grandfather Arsen. I was about 8 years old then. And so, I decided to impress him with my success and I recited a poem about Lenin in an expressive manner.

And then my grandfather grabbed his stick and hit me with it, saying: ‘Bad cess to you and your Lenin, and also to your teacher!’

I didn’t realize what happened then. It all became clear to me only later.

Before the Soviet regime, Arsen Kakabadze served in church. One evening, a stranger knocked on his door and asked to let him stay overnight. Arsen let him into the house, laid a table, poured a glass of wine and the traveler fell into talk.

It turned out that he was a rebel, hiding from the Tsarist secret police. He talked about how the Tsar throttled freedom, about inequality and the class struggle. Although my grandfather didn’t share revolutionary ideas, but he didn’t object and just listened. But then the guest stretched a point and started developing the idea of confiscating land from people and the need for reprisals. My grandfather Arsen got angry and kicked the guest out.

Whereas 1 year later, he discovered that his unbidden guest was a new Soviet leader. It was Joseph Stalin.”

“When I was a 4th-year student at the Faculty of Geology and Geography, we were taken for field practice to the mountains, to Bubi Gorge, Racha region. It’s approximately 3,000 meters above the sea level. We were tasked to find rock crystal (pure quartz) at the Bubistskali River source.

So, once, as I was working there, I noticed an unusual, small piece of something on the river bank. I looked around, made sure that no one could see me, and put that thing into my pocket.

Only a year later, when I started working at the Geology Department, I decided to finally figure out what it was. It turned out that those were fossilized remains of trilobite. It’s a marine animal of the Paleozoic era. In other words, it lived some hundred million years ago! This trilobite generally confirms the scientists’ assumption that the Black and the Caspian Seas constituted a single whole.

To put it short, I finally reported about my discovery, get it off the chest. But this unique trilobite, the only one in Georgia, has been left at my place.