Stalin and Georgia: the history of complicated relations

Stalin and Georgia

At the beginning of 2024, a video shot in the Sameba cathedral in Tbilisi spread on Facebook – one of the icons can be seen depicting Stalin. The “Great Leader” is depicted together with Matrona of Moscow, a saint of the Russian orthodox church.

The video quickly went viral. Mainly, people were outraged and wondered how it happened that an icon of a tyrant, who killed millions, ended up in a church. It soon turned out that the “icon” had been hanging in Tbilisi’s largest cathedral for several months and was donated to the temple by the leader of the pro-Russian party “Alliance of patriots of Georgia,” Irma Inashvili.

The scandal escalated when activist Nata Peradze splashed blue paint on the ‘icon’ – Stalin immediately found defenders, including not only Stalinists but also believers.

Dozens of people in rage came to Peradze’s house, demanding to punish her for vandalism and offending the church.

As a result, Peradze was sent to a detention center for five days. The scandalous “icon” was decided to be removed from the church by the decision of the Patriarchate. However, the reason given was not that Stalin was a tyrant and a murderer of millions, but that “The Russian Church did not include Joseph Stalin’s meeting with Saint Matrona in the canonical text of her life due to insufficient evidence.”

The ruling party also lashed out at “liberals,” not Stalin, and even urgently initiated legislative changes to toughen criminal penalties for desecrating buildings and objects of religious significance.

“This is a campaign led by Georgian pseudo-liberals against the church. They are the modern reincarnation of Bolsheviks with Mausers, eager to remove the domes from the Georgian church,” stated Shalva Papuashvili, the speaker of the Georgian parliament.

The story with the “icon” revived the discussion about Stalin in Georgia. Analysts are sounding the alarm, pointing out Putin’s information war, where Stalin plays a key role, and that Georgian authorities are not resisting this campaign, but rather, supporting it.

Thirty thousand Georgians fell victim to Stalin’s repressions when the population of Georgia was 2.5 million people. Among them were the brightest representatives of Georgian literature, science, culture. Mass graves of repression victims are still being found in Georgia.

Nevertheless, recent studies show that almost 40 percent of the Georgian population has a positive view of Stalin. In a 2023 survey conducted by the CRRC for Zinc Network, 37 percent of respondents stated that “every Georgian patriot should be proud of Stalin.”

Gori, the birthplace of Stalin

The small town of Gori, with a population of 50,000, where Stalin was born and raised, is located 80 kilometers from Tbilisi and 20 kilometers from the Georgian-Ossetian conflict zone, where Russian occupation forces are currently stationed.

During the war in August 2008, when Russia attacked Georgia, Gori was particularly affected. Russian airstrikes destroyed residential buildings in the city center. In the five-day war, 228 civilians died, dozens of them from the city of Gori.

At that time, a six-meter tall statue of Stalin, erected in 1952, a year before the leader’s death, still stood in the main square of Gori. In June 2009, when Mikheil Saakashvili was the president of Georgia, authorities conducted almost a secret operation to demolish it — in the middle of the night, to avoid noise and protests from the local residents, heavy machinery was brought to the square. Stalin was removed from the pedestal at dawn and taken away.

Fifteen years later, Georgia has still not decided what to do with the monument. Currently, it lies face down on the ground in the village of Berbuki in Gori, on the territory of a reclamation enterprise — covered with blue cellophane, presumably, to protect it from rain and sun. The cellophane is now torn and dirty. Around the monument, there is trash and tall dry grass.

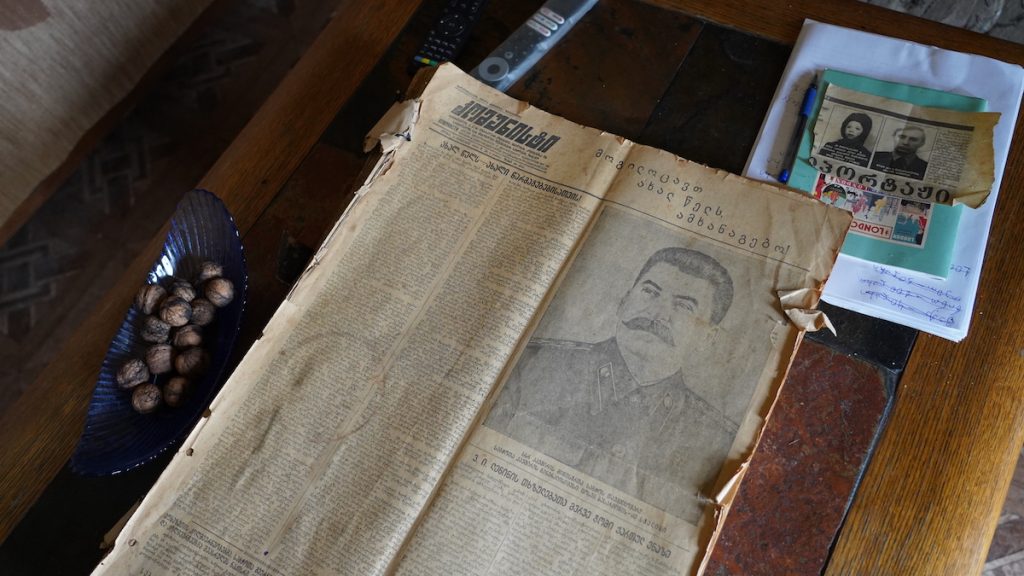

In Gori, the leader still has many admirers. One of them is 50-year-old Zuriko Zumbulidze, a member of the “Stalinist” organization. His home resembles a museum of the “great leader” — huge photographs of Stalin and Lenin, T-shirts with Soviet symbols, a yellowed issue of the “Communist” newspaper, and thousands of other pieces of memorabilia.

“Look where Gori and Stalin’s hut are, and where Moscow and the Kremlin are. He was the poorest man, and look what he achieved! Who would have been accepted in the Kremlin if he had not been a man blessed by God?!” asks Zuriko.

— How about the repressions?

— How would Stalin know that someone in Gori or Telavi was being shot? And if they were, they were bribe-takers. No one repressed scientists. And if they did, it was only those who deserved it.

You will not hear about the repressions of Stalin’s times in the current Stalin museum, which is the most popular museum in Georgia by the number of visitors. In 2023, it was visited by more than 137,000 people. Among the foreigners, the majority are citizens of Russia, China, and Thailand.

The six exhibition halls narrate different episodes of the “leader’s” life, but remain silent about the millions of people deported, repressed, and executed on Stalin’s orders. The museum has a “Repression room,” opened here in 2010 after complaints from outraged tourists. But it is the smallest room in the building with a very small exhibition.

Calls to close the museum are often heard both from local activists and from diplomatic corps representatives. For instance, the Polish Ambassador to Georgia, Mariusz Maszkiewicz, after the beginning of the Russian invasion of Ukraine, advised the Georgian authorities to make a symbolic gesture and close the Stalin house-museum in Gori. For which, as he later admitted, he received a reprimand from the Georgian ministry of foreign affairs.

“Gori was unlucky that Stalin was born here. We want to change the fact that Gori is associated with him,” says Teona Pankvelashvili, an activist and anti-Stalinist from Gori, who asserts that not only Stalinists live in her city.

Teona and her friends, young women from Gori, founded the organization “Maro” and are trying to change the identity of their hometown associated with Stalin. [Maro Makashvili, a Georgian student who volunteered to fight against the Red Army’s invasion of Georgia in 1921 and died near Tbilisi. She was the first woman to become a national hero of Georgia].

“We decided to do everything to convey the correct information to the population. We protest against everything Russian, everything Stalinist. For eight years now, we have been demanding the enactment of the ‘Charter of Freedom’. So that at least the main street in Gori would not bear Stalin’s name,” says Teona.

How Georgia (did not) fight against Stalin

After the Saakashvili government came to power in 2003, Georgia immediately began the fight against its Soviet past. The main part of the de-Sovietization was the dismantling of Stalin monuments and other Soviet symbols in various villages and cities of Georgia, including Gori.

Also, during Saakashvili’s time, in 2011, the “Freedom Charter” was adopted — a law that prohibited Soviet symbolism.

Even then, many experts warned that the de-Sovietization process could become counterproductive, as Saakashvili’s authorities did not try to explain to the ordinary citizens of Georgia why the Soviet era, which many remembered as a time of stability and prosperity, was so bad.

The process of de-Sovietization was superficial and harsh, without public discussion, educational efforts, or the involvement of the local population.

Immediately after the change of power in 2012, the conservatives seemed to take revenge and started a campaign to return the “leader.”

In 2015, the issue of returning the monument to its “rightful place” was brought before the Gori city council, but due to the fierce protest of local activists, as well as the openly negative stance of the embassies, this issue failed.

Experts believe that the ruling party “Georgian Dream,” led by a billionaire who made his fortune in Russia, not only did not hinder this process but, on the contrary, fueled Soviet sentiments.

Journalist Nino Dalakishvili, who is also from Gori, recalls the words of Bidzina Ivanishvili:

“If local residents are proud that [their fellow countryman] Stalin is a symbol of victory over fascism, don’t take this away from the people and don’t irritate them too much,” Ivanishvili says in this video.

“This war [World War II] was won by a Georgian, so it is special,” are the words of former prime minister of Georgia Irakli Garibashvili during a speech in parliament on May 9, 2015.

These statements by government officials cause significant harm to public opinion and help keep Georgia within the Russian orbit, believes historian Irakli Khvadagiani from the organization “SovLab (Laboratory for the Study of Georgia’s Soviet Past)”:

“For Russia, the figure of Stalin holds strategic importance. It uses him for political purposes, to strengthen its own influence. Its satellite regime in Georgia behaves in a similar manner.”

According to the non-governmental organization “SovLab,” which is involved in the study of the Soviet past, since the “Georgian Dream” party came to power in 2012, 12 new monuments to Stalin have been erected in various villages and cities of Georgia.

Experts attribute the rise of several pro-Russian political organizations and groups in the country in recent years to the policies of the “Georgian dream.” These organizations often travel to Moscow. While there, they pose in front of the Kremlin and declare that their mission is “to continue the great deeds of Stalin.

For instance, members of the pro-Russian organization “Alt-Info” traveled to Moscow in October 2022 and stayed for over 20 days. Although they did not meet with Putin, they used the trip to enhance their image on social networks. They posted numerous photos of themselves at prominent locations, including Red Square and Stalin’s tomb, where they were seen laying flowers.

Interestingly, the financial and ideological connection of the “Georgian dream” government with pro-Russian radicals has been confirmed more than once.

Myths about Stalin: “The great Georgian who ruled the world”

One of the reasons for Stalin’s popularity in Georgia, experts say, is his ethnic origin. The fact that someone from this small country rose so high is a source of pride, especially for the older generation.

Historian Irakli Khvadagiani says that the cult of Stalin helped generations of Georgians create a distorted model of nationalism, and modern Georgia has been unable to help overcome these complexes:

“Despite not having your own state, national attributes, not knowing and not teaching your history, being isolated from the external world by the Iron curtain, you can still be proud of your origin because a man born on your land rules such a large country, rules the world. This is how it worked during the USSR and, by inertia, it still works now.“

In Georgia, many myths about Stalin still circulate. In Gori (and not only there), you will be told about how Stalin loved Georgian culture, traditions, folklore, and how he served Churchill Georgian wine.

Journalist David Paichadze, who teaches Georgian language and literature at school, believes that the main reason for Stalin’s popularity is “insufficient education and lack of public awareness.”

The Soviet past is barely studied in schools, and state policy in this regard is not effective, say other experts. They believe that the country has not undergone the necessary process of coming to terms with its Soviet past after the dissolution of the USSR.

According to the latest survey conducted by CRRC in 2015, 35 percent of respondents said they learned nothing about Stalin in school. Meanwhile, 38 percent received only positive information.

As Irakli Khvadagiani notes, there has been no significant progress since then—the post-Soviet period is still covered in only a few chapters in Georgian schools.

“The Middle Ages are given too much time, the focus is specifically on them, while the twentieth century, which was key for us, receives very little attention. Why?! Because in the twentieth century, the aggressor was Russia, which is not convenient today, while in the Middle Ages, the aggressors were others,” says Giorgi Kandelaki, a researcher from the organization “SovLab.”

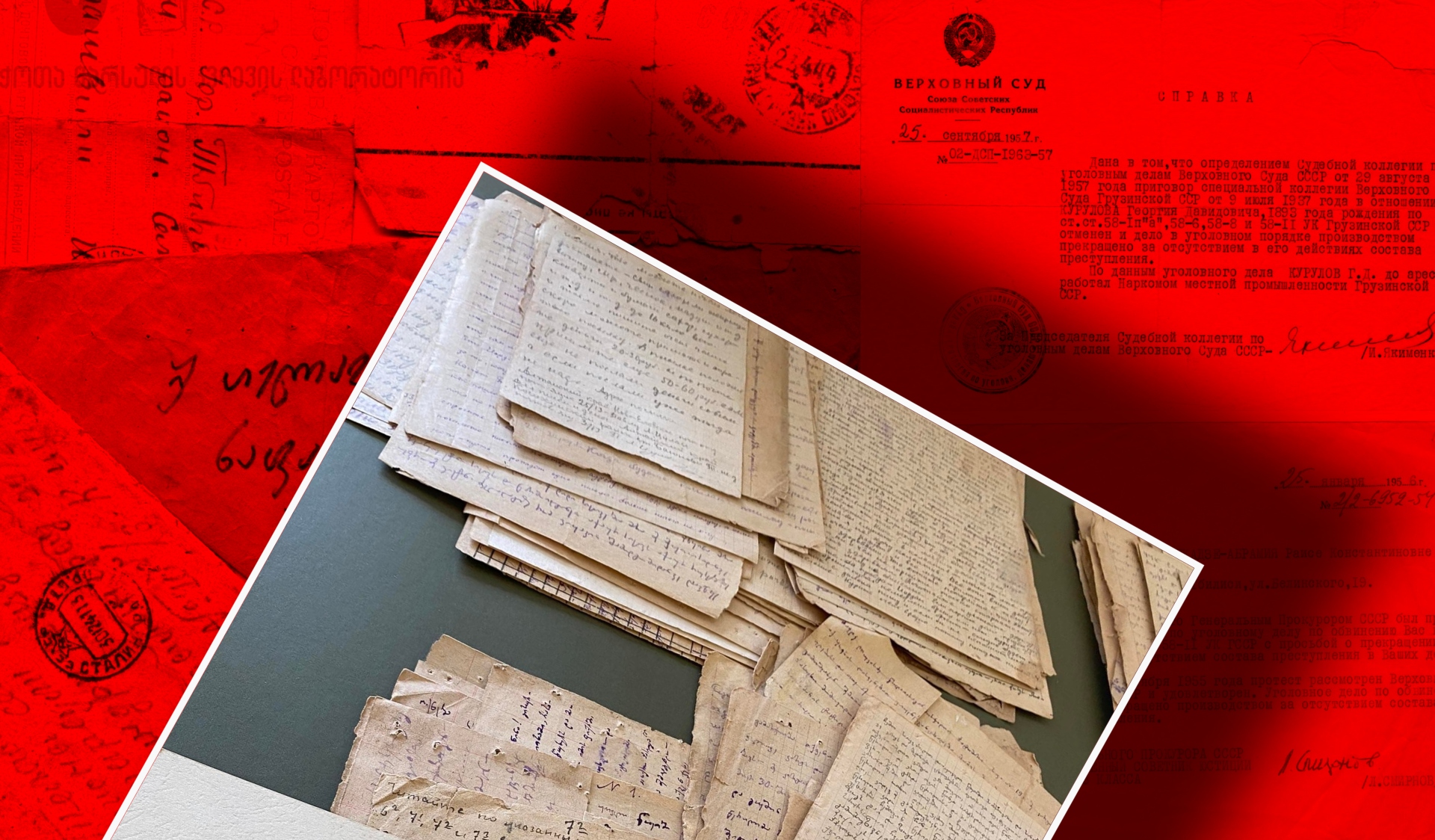

Georgian researchers of Soviet history also say that the government hinders the study of the Soviet past not only in schools.

For several months now, researchers have had limited access to the ministry of Internal affairs archive, where unique documents are stored. The archive is completely closed. The official reason is reorganization. But historians do not believe this. They think the government is deliberately making it difficult to research the Soviet past.

“What’s the purpose? The long-term goal is to disorient society in Georgia, to ignite anti-Western sentiments and increase pro-Russian sympathies, which is facilitated by ignorance of the past and a lack of information about Russian imperialism and the totalitarian past “, says Khvadagiani.

Stalin and the church

Another common myth in Georgia about Stalin is that he was a believer.

In a CRRC survey, 41 percent of respondents stated that Stalin was a religious person, although under his rule, hundreds of churches were demolished and hundreds of religious figures were repressed.

Independent theologians also say that the cult of Stalin in Georgia is developed by the orthodox clergy and the Georgian orthodox church.

Theologian Mirian Gamrekilashvili tells JAMnews that in the Georgian Church, “the majority of clergy sympathize with Stalin.”

For example, this quote belongs personally to the Catholicos-Patriarch of Georgia Ilia II: “He was Georgian by origin and knew the Georgian language, Georgian songs, church hymns well. At the time of his death, I was a student at the seminary. We all stood in the hall and cried when he was buried. Stalin was an outstanding personality; such people are rarely born. He knew, understood the global significance of Russia.”

“The church is the pillar number one of Russian politics in Georgia,” says Gamrekilashvili. “Russia very successfully uses religious ties to strengthen its political influence worldwide and, of course, in Georgia. Putin doesn’t hide this — in interviews with Tucker Carlson, he repeatedly mentioned orthodox culture. The Kremlin clings to orthodoxy as the main political tool for manipulating Georgian society.”

“Georgia against Joseph Stalin”

In February, “Sovlab” launched a new book by Georgian writer Lasha Bugadze called “Georgia against Joseph Stalin,” which draws on archival materials.

“Sovlab” researcher Giorgi Kandelaki points out that while much has been written about Stalin, his specific impact on Georgia has barely been explored. This book marks the first effort to discuss Stalin’s direct influence on Georgia’s fate.

Kandelaki finds it incredible that more than 30 years after Georgia regained independence, most Stalin-related literature merely mentions Georgia as his birthplace.

The book aims to debunk major myths about Stalin, particularly concerning the Russian occupation.

In Georgia, many still believe that in 1921, it was Lenin who ordered the Red Army to invade [Georgia], while Stalin was against the occupation. However, archival documents confirm the opposite — it was Stalin who personally issued such an order secretly from Lenin.

“Those who are ready to abandon myths and need concrete arguments about what Djugashvili did to Georgia will find them in this book,” says Lasha Bugadze.

What Georgia needs to do to defeat Stalin

Researchers studying Georgia’s Soviet past agree that Russia is trying to spread myths about a common past and thus maintain its influence in the country.

The “icon” of Stalin in the Sameba Cathedral is one such example, but not the only one.

For instance, in 2022, several actors from the Batumi State drama theatre refused to perform in a play based on Mikhail Bulgakov’s “Batumi” about the life of the young Joseph Stalin. The play, which portrayed not Stalin’s cruelty but his “heroism,” was directed by former member of “Georgian Dream” Nukri Kantaria. The staging of the play about the dictator is one of the elements of promoting Russian propaganda, human rights defenders claimed at the time.

“The entire Soviet state machinery worked for decades to deprive people of critical thinking, and they succeeded. But restoring moral guidelines is not an easy process,” notes psychologist Jana Javakhishvili.

According to researchers, there are two things that Russia uses most effectively to influence Georgia — religion and the phenomenon of Stalin.

“In this years-long information war, which cultivates anti-Western, ethno-religious nationalism, the figure of Stalin serves as a kind of unifying center, an umbrella. Today, Russian propaganda tries to present Stalin to Georgians as a symbol of patriotism, as a national symbol,” says Kandelaki.

What does Georgia need to do to rethink its Soviet past?

First and foremost, this requires political will and a change in state policy, experts believe.

“There is no state policy that opposes Soviet myths and Russian propaganda. And the work of small organizations like ours cannot fill the entire space and counter disinformation and propaganda,” says Irakli Khvadagiani from “Sovlab.”

“We need knowledge, knowledge, and more knowledge. We do not know much about our own history, and propaganda takes advantage of this,” says Giorgi Kandelaki.

“Open archives, a new concept of education… we need critical thinking and freedom. A free educator. Because a teacher tied to politics cannot teach a child freedom,” says journalist David Paichadze.

*Supported by the media network