Separatism charges against Talysh in Azerbaijan: who is threatened by Lankon?

Problems of the Talysh in Azerbaijan

Posts by Hope Party chairman and former MP Igbal Agazade on certain place names have once again fueled public and political rhetoric targeting the Talysh community in Azerbaijan.

His questions such as “Why are Lankaran and Astara called ‘Lankon’ and ‘Ostoro’ in everyday messaging and social networks?” sparked discussions online. The main argument linked to these remarks is that “politicians acting as unofficial representatives of the authorities are testing public opinion.”

In his social media post, Agazade suggested that using these place names might be deliberate propaganda, accused some individuals of separatist activities, and noted that they stayed silent during the 44-day war and the “anti-terrorist operation.”

According to him, expressing political views through “Talysh toponyms” is intentional. These accusations illustrate how positions tied to Talysh identity are being artificially framed as dangerous.

Context and political reading

Agazade’s post has been portrayed both as a call for uniform use of the state language and as symbolic pressure denying minority identities.

By using phrases like “propaganda through toponyms” and “separatist positions,” the rhetoric goes beyond a linguistic issue. Agazade’s statements are not simply about pronunciation—they carry codes of dangerous rhetoric for Azerbaijan’s multiethnic society. Denying “the language of others” highlights not cultural diversity but a state ideology aimed at suppressing it.

Meanwhile, intellectuals and activists counter that the Talysh language and its place names are a living, historic, and legally grounded reality.

“Reed houses” and “erasing memory”

One response on social media came from Lankaran resident Enver Shahkubadbeili, who noted that the name “Lankon” in the Talysh language is historically rooted and means “reed houses.” He stressed that this is not just a phonetic difference but a cultural trace reflecting Talysh roots in the region:

“I have lived in Lankaran for 64 years. The Talysh call it ‘Lankon,’ and Astara ‘Ostoro.’ This is their native language. How do you (addressing Agazade) intend to erase that from their memory?”

He warned that rhetoric implying such bans could have serious consequences, recalling that the emergence of figures like Alikram Humbatov, a leader of the Talysh national movement, was also tied to this kind of attitude.

“Empty statism policy”

A sharper and more ironic response to Agazade came from activist Emin Nihil. He compared such rhetoric to outdated Soviet stereotypes about statehood:

“This is the face of the same generation of politicians: all like cucumbers from one patch — empty talks about statehood, the nation, and old clichés.”

Emin Nihil emphasized that such rhetoric is aimed not only against the Talysh people but also against all small ethnic groups in Azerbaijan and the very concept of pluralism. In his opinion, having an official state language cannot justify the suppression of other languages.

“Isn’t assimilation enough?”

The head of the Azerbaijani Students Association in Turkey, Seymur Agaev, regarded Iqbal Agazade’s rhetoric as “direct or indirect service to separatism”:

“Isn’t there already enough years of assimilation of the Talysh, artificially reducing their numbers in statistics? Now you are attacking the historical Talysh toponyms?”

Seymur Agaev called the rhetoric regarding toponyms an “insult” against the background that the Talysh language is not taught, there is no infrastructure in the region, unemployment is high, and the language has no official status. He also noted that equating the status of the Talysh and Armenians in Agazade’s text is “an attack on the identity of the people.”

- Tbilisi: A city where Armenians and Azerbaijanis can be friends despite the war

- How to make Lezgin ‘sun’ bread – 10 photos

Agazade’s response

After receiving criticism, Iqbal Agazade published a second post in which he tried to clarify his position. He stated that he does not hate small ethnic groups and loves the various peoples of Azerbaijan as a “symphony of the country’s colors.” However, he again emphasized the “need to write toponyms in the state language” and expressed concern that this “is taking the form of dangerous propaganda.”

This post further intensified the situation because a significant part of society no longer considers his first statement accidental, but perceives it as an unofficial test of public reaction on behalf of the state.

Status of the Talysh language: only optional teaching and only in primary school

The Talysh language does not have official status in Azerbaijan. At present, it can only be taught as an optional subject for 2 hours per week in primary schools in the region.

However, in practice, such lessons are often not conducted in many schools. There is no teaching of the Talysh language in secondary or higher education.

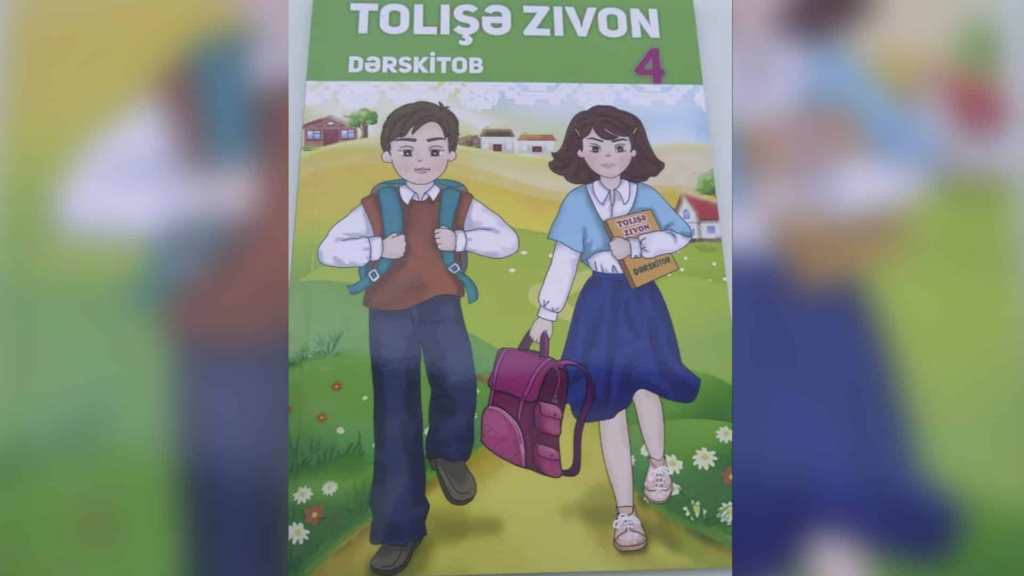

Textbooks published by the Ministry of Education are either outdated or do not meet modern pedagogical standards. A new textbook published in 2023 has also been criticized for being prepared without consulting the Talysh community.

There are no teacher training programs for the Talysh language. The lack of teaching aids, terminological dictionaries, and materials for unifying dialects negatively affects the overall level of instruction. Additionally, there is a severe shortage of teachers.

Existing teachers often lack sufficient training in grammar and the standardized form of the language. There are no state programs for training educators.

The Talysh language is divided into several dialects (Lankaran, Astara, Lerik, etc.), but there is no unified standardized form. In the 1990s, a writing system based on the Azerbaijani alphabet was adopted but did not become widely used. This complicates the development of a unified curriculum.

Talysh is the native language of the Talysh people living in the Talysh region of Azerbaijan (districts of Lankaran, Astara, Lerik, Masally, and Yardimli) and belongs to the Northwestern branch of the Iranian languages.

UNESCO classifies it as “endangered,” yet its broader teaching in Azerbaijan is often associated with separatism or foreign influence (Iran, Armenia).

These narratives are mainly promoted through pro-government channels.

Private initiatives such as language courses or clubs often face oversight and pressure. Police disperse events dedicated to the native language or prevent them from being held altogether.

The exact number of Talysh language speakers in Azerbaijan is unknown because official statistics do not reflect these data.

According to rough estimates, the Talysh make up about 2–3% of the country’s population (approximately 112,000 people), but unofficial figures vary up to 800,000.

The Talysh are generally bilingual: they use Azerbaijani as the official and educational language and Talysh in daily life and within the community. However, the dominance of Azerbaijani and the absence of Talysh in the official education system limit its functionality.

According to the Constitution of Azerbaijan, conditions should be created for the development of other languages, but in practice, the Talysh language has no official status and receives no systematic state support.

Cultural and media restrictions

Although Talysh folklore, music, and oral traditions are rich, the opportunities to express this heritage are limited. Newspapers, radio, and television programs in the Talysh language are either completely absent or heavily restricted.

Informal initiatives are regarded by the state as “grounds for separatism” and placed under control. Cultural events held locally are either conducted under official supervision or not permitted at all.

This policy affects not only culture but also collective memory. The renaming of toponyms and suspicion toward local names appear as a strategy of erasing collective memory.

Talysh activists and experiences of repression

Talysh human rights defenders and cultural activists have periodically become targets of the state:

- Novruzali Mammadov, Doctor of Philology, was arrested in 2007 on espionage charges for publishing a magazine in the Talysh language. He died in prison in 2009. Human rights defenders and Talysh activists consider his death suspicious.

- Hilal Mammadov, known for the video “Haray haray, mən Talışam” (“Hey, I am Talysh!”), was arrested in 2012 on charges of “activities against the state.”

- Fakhreddin Abbaszoda was accused of “inciting ethnic, national, and religious hatred.” Reports stated that he committed suicide in prison on May 8, 2020. The official statement said: “Fakhreddin Abbaszoda could not bear the liberation of Shusha and committed suicide.” Human rights defenders, however, considered his death suspicious.

- Iqbal Abilov, a young researcher known for his work on ethnicity, was sentenced to 18 years in prison on charges of “treason.” As evidence, authorities cited his academic publications in journals linked to Armenia and his contacts with Armenian scholars, but no guilt was proven. He is recognized as a political prisoner.

These cases have reinforced the tendency to interpret Talysh activism as a political threat.

Parallels with Armenians in rhetoric and the factor of Alikram Humbatov

Linking the discussion of the Talysh language and toponyms to Armenia is a common tactic in Azerbaijani political discourse.

In this context, the short-lived Talysh-Mugan Autonomous Republic, declared in 1993 by Alikram Humbatov and lasting two months, is often recalled. After Heydar Aliyev came to power, this initiative was shut down, Humbatov was arrested, pardoned in 2004, and then forced to leave the country.

He spent the last years of his life in the Netherlands as a political émigré.

Officially, Humbatov’s activities were classified as separatism. However, organizations such as Amnesty International and the Council of Europe recognized him as a political prisoner.

Later, his activities were mainly focused on advocating for cultural and legal rights.

Particularly controversial was the statement by party chairman Iqbal Agazade, where Talysh language speakers were equated with supporters of the separatist regime in Nagorno-Karabakh.

The topic of the Talysh-Mugan Autonomous Republic, declared by Humbatov, is still used in public discourse as a fear-mongering element, including claims of alleged Armenian support for this project.

Nevertheless, independent researchers and human rights defenders emphasize that the overwhelming majority of Talysh activism, including calls for autonomy, remains within the framework of legal and cultural rights and has no connection with Armenia.

News in Azerbaijan