Russia-Azerbaijan tensions deepen amid arrest of diaspora leader and Crocus City Hall terror trial

Russia-Azerbaijan tensions

Amid growing tensions between Russia and Azerbaijan in recent months, two key developments have drawn particular attention: the arrest of Shahin Shikhlinski, head of the Azerbaijani diaspora in the Ural region, and his son Mutallib — with a possible prisoner exchange on the table — as well as the ongoing trial over the 2024 terrorist attack at Moscow’s Crocus City Hall.

Arrest of Ural diaspora leader and the prospect of a prisoner swap

In late June, Russian law enforcement carried out a large-scale raid targeting the Azerbaijani community in Yekaterinburg. Dozens of Azerbaijanis were detained, and two brothers — Ziyaddin and Huseyn Safarov — died under mysterious circumstances, with signs of torture on their bodies.

Baku claims the men were brutally beaten and killed by Russian police. The incident became a tipping point in already strained relations, which had worsened after Russia shot down a passenger plane belonging to Azerbaijan Airlines (AZAL) in December 2024.

The crash killed 38 people. Baku blamed Moscow and demanded accountability, while the slow pace of the investigation by Russian authorities has further fuelled anger in Azerbaijan.

Tit-for-tat moves

Following the events in Yekaterinburg, Azerbaijan issued a sharp diplomatic protest to Russia. Cultural events linked to Russia were cancelled, and several Russian nationals living in Azerbaijan were arrested.

Several Russian citizens were detained in Azerbaijan, including journalists accused of espionage, IT specialists, and tourists. Photos of the detainees were released showing clear signs of having been beaten.

After the images surfaced, some Russian bloggers described the situation as a “cruel public humiliation campaign”. In response, Russia ramped up pressure on Azerbaijanis living on its territory. As part of a special investigation, Russian authorities detained Shahin Shikhlinski, head of the Azerbaijan-Ural diaspora organisation, along with his son Mutallib Shikhlinski.

According to Russian media, the father’s arrest is officially linked to the reopening of a 20-year-old murder case. However, the broader context suggests he was targeted as part of the recent escalation. Shikhlinski was first detained on 1 July but released after questioning as a witness. When his son Mutallib was arrested in mid-July, a warrant was again issued for the father’s arrest.

Shahin Shikhlinski reportedly spent some time hiding at the Azerbaijani embassy in Moscow. In early August, as he was leaving the embassy grounds, he was detained by Russian police and transferred to Yekaterinburg. He now faces criminal charges for allegedly using violence against a public official.

According to the prosecution, during the July raid, Mutallib Shikhlinski allegedly drove a car towards a police officer in an attempt to prevent his father’s arrest, hitting the officer and causing injuries. Mutallib himself claims it was an accident and says he regrets what happened.

Speculation over a possible prisoner swap

Against this backdrop, Russia and Azerbaijan appear to be holding each other’s citizens as de facto hostages. Despite heated rhetoric on both sides, officials are avoiding open confrontation while trying to manage public opinion at home.

According to media reports, the Kremlin’s strategy is to stay publicly silent on the issue, “buy time and de-escalate tensions.” Behind the scenes, Russian authorities are said to have opened negotiations with Baku through Turkey and other informal channels.

In this context, some Russian sources — including the popular Telegram channel Nezygar — claim that Moscow is considering exchanging the Shikhlinski family for the Russians detained in Azerbaijan.

There are reports that several leaders of the Azerbaijani diaspora arrested in various Russian regions — including Shikhlinski — have already been released, and that efforts are underway to repatriate the Russian citizens held in Azerbaijan. According to official statements, Moscow aims to bring its citizens home, even if they have not “expressed a willingness” to leave Azerbaijan voluntarily.

These developments are seen as a sign that both sides are quietly seeking mutual concessions. After their initial detention, Shahin and Mutallib Shikhlinski were released, and although they were later targeted again, reports suggest this was part of an internal investigative process within Russia. In turn, Baku also moved to release or deport some of the detained Russian nationals.

For instance, several Russian journalists arrested in early July were reportedly sent back to Russia shortly after their detention. This apparent easing of measures on both sides suggests that an informal prisoner swap agreement may already be underway.

Legal mechanisms

Officially, what is known as a “prisoner exchange” typically applies between states at war or in serious diplomatic crisis. While Russia and Azerbaijan are not formally at war, the current situation may be seen as a form of crisis.

Legally, arranging such an exchange is complicated, as both sides are holding their citizens on criminal charges. In practice, however, several mechanisms exist — including amnesty, extradition, or deportation.

For instance, Moscow could reduce the charges against the Shikhlinski family and deport them to Azerbaijan by declaring them persona non grata. In response, Baku could deport the detained Russians and hand them over to Russian authorities. Both sides could present the move as an act of goodwill or frame it as the continuation of their sentences in their home countries.

There is precedent. In 2012, Azerbaijani officer Ramil Safarov, sentenced to life in Hungary, was extradited to Azerbaijan on the condition that he would serve the rest of his sentence there. However, he was pardoned by the Azerbaijani president immediately upon arrival. The move sparked a diplomatic scandal between Hungary and Armenia, but it showed that repatriating convicted individuals for national interest is possible.

Another example is the case of Alexander Lapshin. In 2017, the Russian-Israeli blogger was detained in Belarus and handed over to Baku. Although he was sentenced to three years in prison, he too was later pardoned by the Azerbaijani president.

In both cases, formal extradition procedures were followed, but the outcomes were shaped by political decisions. A similar model could be applied in the case of the Shikhlinski family and the Russians detained in Azerbaijan.

If a deal is reached, Russia could transfer the Shikhlinskis to Azerbaijan for further investigation there, while Azerbaijan could deport the Russian nationals. The laws of both countries allow the president to issue amnesties in such cases.

Diplomatic aspects

The Shikhlinski case has highlighted a deepening atmosphere of mistrust between Russia and Azerbaijan.

Some Russian commentators claim that Baku is deliberately taking Russian citizens “hostage” in an effort to undermine Moscow. In Azerbaijan, meanwhile, despite Russia’s long-standing image as a “strategic partner,” reports of violence against Azerbaijanis have fuelled growing anti-Russian sentiment.

In this climate, both governments have tried to control the public rhetoric. Russia’s Foreign Ministry has avoided making the issue public, while Kremlin representatives have issued only vague statements, saying they are “conducting an investigation.” Azerbaijan, for its part, has maintained that it will not interfere in Russia’s internal affairs, while insisting on the protection of its citizens’ rights.

There have also been signs of mediation efforts from partners like Turkiye. According to reports, Ankara has sought to calm both Moscow and Baku and prevent further escalation. If a prisoner swap does go ahead, it would signal a willingness by both sides to compromise.

Backroom deals between Moscow and Baku are not without precedent. In 2016, Russia reportedly handed over a group of Azerbaijani businessmen who had been under arrest, in exchange for certain gestures from Baku — although this was never officially confirmed.

While no public acknowledgement has been made this time either, there are indications that diplomatic negotiations are underway behind the scenes. Shahin Shikhlinski has not yet been released, but the investigation into his case has reportedly slowed down, while most of the Russians detained in Azerbaijan have already returned home.

This quiet de-escalation, without public apologies or admissions, suggests both countries have made concessions. Analysts note that with the war in Ukraine ongoing, neither Moscow nor Baku has any interest in opening a new front — making “quiet diplomacy” the preferred path for containing the crisis.

Crocus City Hall terror trial and the Agalarov family

On 22 March 2024, a terrorist attack took place at the famous Crocus City Hall concert venue in Krasnogorsk, just outside Moscow. Four armed men stormed the building shortly before a concert was due to begin, opening fire on the crowd with automatic weapons, attacking people with knives, and throwing explosive devices — setting the building ablaze.

The attack left 145 people dead and more than 550 injured. According to official data, nearly half of the victims died not from gunshot wounds, but from smoke inhalation and exposure to toxic gases caused by the fire.

It was the deadliest terrorist attack in Russia since the Beslan school siege in 2004.

The initial investigation revealed serious security violations at the venue, which significantly contributed to the high number of casualties.

Igor Trunov, a lawyer representing survivors and the families of the victims, said the theatre curtain — which was supposed to be fire-resistant — ignited in seconds. Many emergency exits were locked, and the smoke ventilation system failed to operate. As a result, people were unable to escape, and the death toll rose. Crucial safety systems that could have reduced the impact of incendiary devices either malfunctioned or were missing altogether.

Immediately after the attack, the authorities killed the assailants and detained 12 suspects. Responsibility was claimed by ISIS-K, the Afghan affiliate of the so-called Islamic State group.

However, Russian officials sought to shift blame to Ukrainian intelligence services. President Vladimir Putin called the attack a “barbaric act of terrorism carried out in Ukraine’s interests,” a claim Western governments rejected as “unfounded disinformation.”

In addition, US intelligence had reportedly warned Moscow weeks earlier about a potential terrorist threat, but, according to media reports, Russian officials failed to take the warnings seriously.

The trial and the Agalarov family

Around a year and a half after the Crocus City Hall attack, in August 2025, the criminal trial opened at the Moscow Military Court. Nineteen defendants are facing charges — four of them the direct attackers, and 15 others accused of aiding and abetting the attack.

All the accused are originally from Tajikistan and were living in Russia as migrant workers. On the first day of the trial, the four main defendants pleaded guilty — three fully, and one partially.

However, human rights groups and independent observers have questioned the validity of the confessions, noting visible signs of beatings and torture on the detainees shortly after their arrest. In one video circulated online, a captive is seen having his ear cut off and being forced to eat it.

Despite objections from the defence, large portions of the trial are being held behind closed doors at the request of prosecutors. Evidence is not available to the public or the media.

Opposition politician Gennady Gudkov said openly that “this trial looks like an attempt to cover up the lack of a real investigation.” According to him,

the authorities are scapegoating the detainees instead of identifying the real perpetrators and understanding how the security failure occurred.

Indeed, the scale of the attack pointed to serious lapses in Russia’s internal security. Despite warnings from Western intelligence services, Russian authorities ignored the threat. Just three days before the attack, Vladimir Putin dismissed the alerts, calling them “scare tactics.”

Independent media outlets have argued that the attack was made possible by the fact that Russia’s security agencies, preoccupied with the war in Ukraine, had neglected domestic counterterrorism efforts.

A key moment in the trial came when questions were raised about the potential responsibility of the owners of Crocus City Hall — the prominent Agalarov family.

The concert venue, along with the adjacent shopping and entertainment complex, is owned by Crocus Group, headed by well-known businessman Aras Agalarov and his son, singer and entrepreneur Emin Agalarov. Aras, originally from Azerbaijan, is known for his large-scale construction and commercial projects in the Moscow region. Emin plays a significant role in the family business alongside his music career.

From 2006 to 2015, Emin Agalarov was married to Leyla Aliyeva, the daughter of Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev, linking the Agalarov and Aliyev families. Due to these ties and Aras Agalarov’s close relations with Azerbaijan, the family is well known in both countries. Emin Agalarov has even been awarded the title of People’s Artist of Azerbaijan.

Following the attack, the management of Crocus City Hall released a statement in which Aras Agalarov claimed that the venue’s fire safety systems were functioning properly, but that the staff were powerless against heavily armed attackers. He said that “many employees heroically helped evacuate the audience” but had no means to resist the assailants.

Nevertheless, families of the victims soon filed lawsuits against Crocus Group. In April, a group of victims represented by lawyer Igor Trunov launched a civil suit accusing the venue’s owners of negligence regarding fire safety. The suit cites failures such as locked doors, a non-functioning smoke ventilation system, and other critical violations.

According to RIA Novosti, dozens of victims have already filed claims seeking compensation from the Agalarov family.

While Russian authorities initially treaded carefully around the issue, by the start of the trial the tone of pro-Kremlin media and Telegram channels had noticeably hardened.

On 5 August, following one of the hearings, several media outlets reported that criminal proceedings could be opened against the management of Crocus City Hall. One of the most vocal critics was Vitaly Borodin, head of the “Federal Security and Anti-Corruption” project and a figure known for his closeness to the Kremlin. He openly demanded: “The Agalarovs must be stripped of Crocus.” According to Borodin, Aras and Emin Agalarov fled the country, leaving behind massive debts to Russian banks.

Borodin claimed the Agalarovs had received large loans from Russian banks to fund construction in the Moscow region, but diverted much of the money into major projects in Azerbaijan.

In recent years, the Agalarovs have built the luxury Sea Breeze resort on the Caspian coast near Baku, which now hosts annual international music festivals.

Borodin alleged that after the terror attack, Emin Agalarov complained about being “drowning in debt,” yet continued building in Baku using funds siphoned from Russia. “The Agalarovs are already on the run,” he said. “They took out loans in Russia and fled. Soon, we’ll likely see Crocus placed under state control.”

Agalarovs leave Russia

On the eve of the trial, reports emerged that Aras Agalarov had left Russia and flown to Baku. Around the same time, his son Emin posted photos on Instagram taken at the Sea Breeze resort in Baku. Both members of the family are currently believed to be in Azerbaijan. It remains unclear whether they plan to appear in court in Russia.

At present, no formal charges have been brought against the Agalarovs, though investigators are reportedly gathering materials for a potential case of “negligence.” In effect, the family has taken refuge from the Russian justice system by remaining in Azerbaijan. Although Aras Agalarov holds Russian citizenship, Azerbaijan is under no obligation to extradite him — especially in the absence of a formal conviction.

At the same time, Russian authorities may choose not to push the issue.

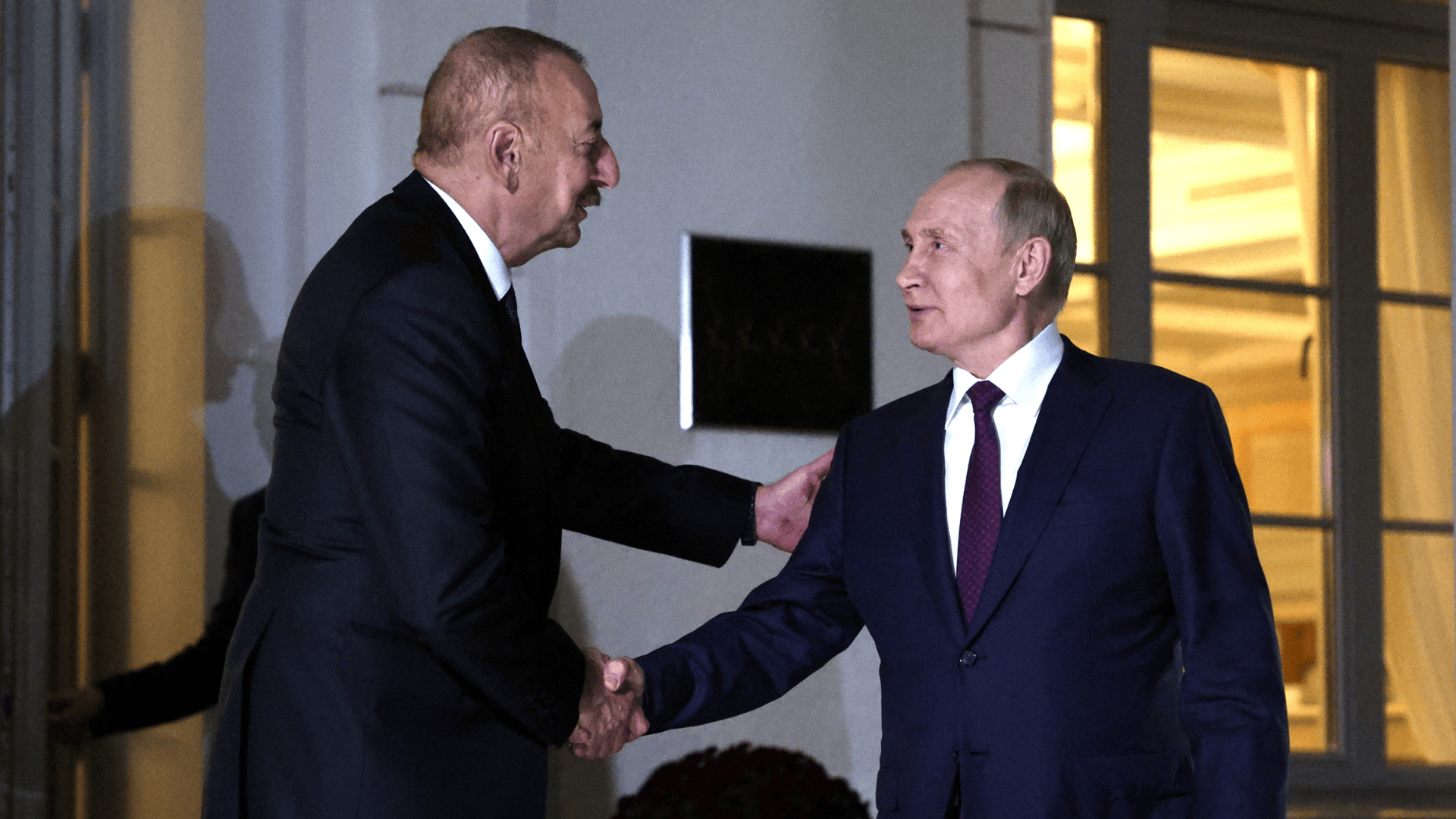

Experts note that pursuing legal action against a man who was once married into president Ilham Aliyev’s family — and is the father of his grandchildren — could seriously strain Moscow’s relationship with Baku.

This leaves the Kremlin in a difficult position: either respond to domestic pressure by prosecuting the businessmen, or keep the case quiet to avoid damaging ties with a strategic partner.

News from Azerbaijan