Ponichala, a country on its own

An Azeri boy politely gave up his seat for me on bus #44, at the Collective Farm Square. A conversation in Armenian can be heard from behind me and someone to my left is speaking in Russian. A small bus, packed to the brim with people, is slowly heading towards the southern part of Tbilisi, deep into the outskirts of the city.

An Azeri boy politely gave up his seat for me on bus #44, at the Collective Farm Square. A conversation in Armenian can be heard from behind me and someone to my left is speaking in Russian. A small bus, packed to the brim with people, is slowly heading towards the southern part of Tbilisi, deep into the outskirts of the city.

Ponichala belongs to the Krtsanisi district of Tbilisi. Until now it has been regarded as a non-urban settlement. Earlier, it was part of the Gardabani district, where the local population primarily cultivated vegetables and bred livestock. As time passed, a number of factories were put into operation here at the same time as when the Rustavi highway was being constructed. In the early 1970s, multi-storey residential buildings were constructed with the aim of encouraging work and development in the area.

There are no longer any large enterprises such as former electric welding plants or fisheries that remain in operation.

Now, there are some small businesses emerging in their wake. Some have adapted the waste area of the former factory into a furniture workshop, while others have used it as a packaging plant or a scrap metal collection point.

Thus, Ponichala is gradually undergoing an industrial rebirth.

It looks like a separate world – equally isolated from both Tbilisi and Gardabani.

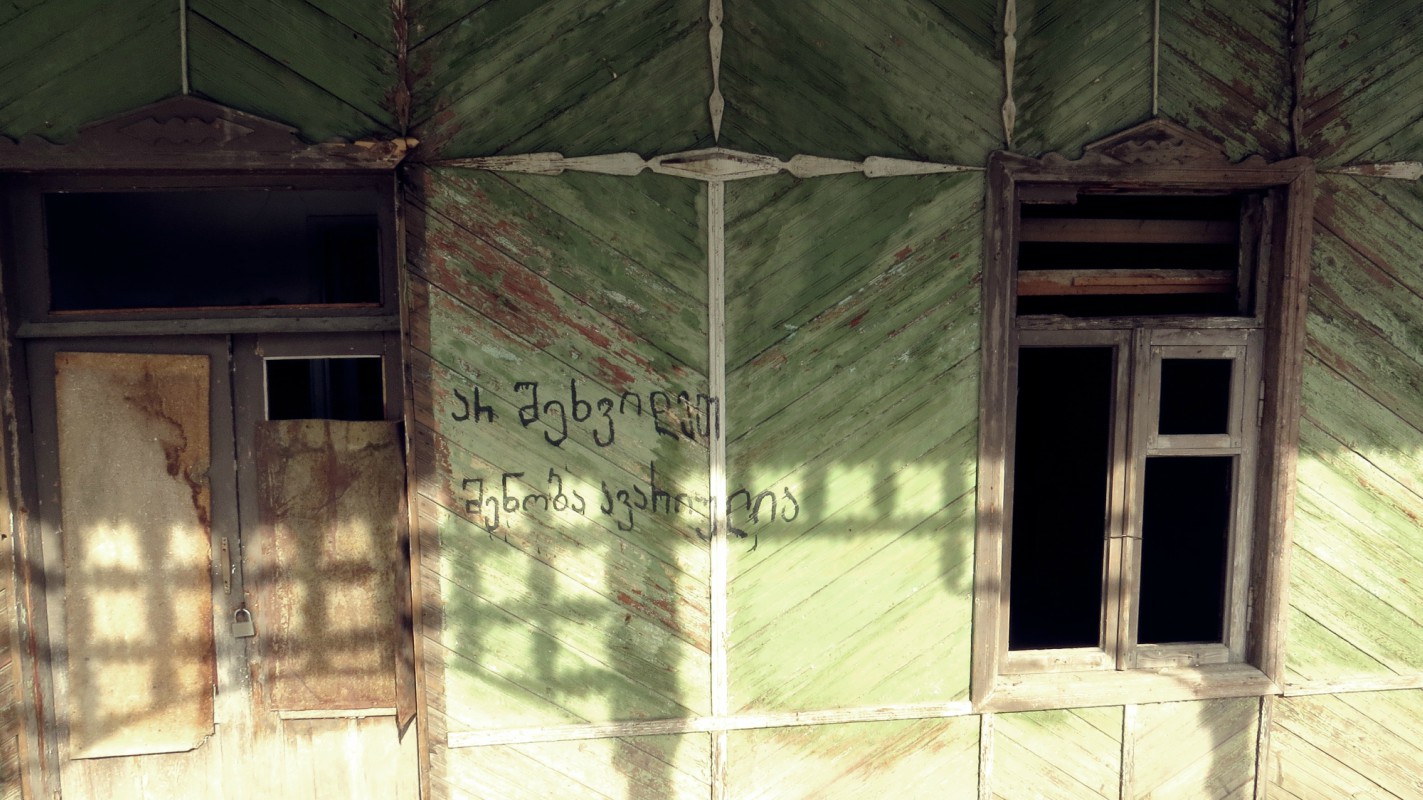

The bus terminal in upper Ponichala is the starting point of my ‘journey.’ It’s not far from here to the ‘Ponichala’ railway station. Its platform is functioning, but the station building with carved decorations is now virtually moribund. A sleepy station employee tells me that a district ‘commuter train’ and a train to Armenia will pass by here.

Georgians, Greeks, Armenians and Azerbaijanis have been living side by side in upper Ponichala for years. There are Greek and Armenian districts which are situated near the railway station. Ali Ajibekov, an elderly resident of Ponichala, walked down the narrow road of the private settlement, telling me about the old days. As he told me, the Greeks left this area in the 1990s.

“That’s where the Greeks used to live,” he pointed with his hand. “They sold their houses and left the area. We got on well with each other and we never quarreled.”

Ali says Georgia is a country where people consider it to be their homeland, irrespective of their ethnicity and religious belief.

All blocks of flats in Ponichala look very much alike and this monotony unconsciously brings one back to the Soviet era.

Women wearing headscarves are selling second-hand clothes which hang from a rope near the pre-kindergarten. There are numerous ‘booths’ selling sundries and alcohol similar to those in Tbilisi back in the 1990s. One of them is called ‘Broadway.’

He pointed out the plain locked building of the banquet hall. The local men in a cafe with a plastic interior were scowling at me, a stranger in these parts, wondering if I happen to be from the district administration.

Ponichala was a real gangster area in the 1980’s to 1990s. Drugs were freely sold here and matters were settled using firearms.

Now, things are not going too well either. Ponichala rarely gets shown on the central TV channels’ news programs and even if it does, it’s only about the crime.

“An attack in Ponichala – a 47-year-old man received multiple injuries to his chest”

“A mother was found with her throat cut, a child burned to death – massacre in Ponichala”

“Samira Bayramova, 17, kidnapped from Ponichala”

“Pikrat Akmedov, 23, killed in Ponichala,” reads the report on Rustavi 2’s website, published in 2016.

Locals say that the young people have lost their interest in life and the government has forgotten about them.

Nina became a widow during the August war. Her pension was hardly enough to make ends meet, so she has started a small business – she sells vodka in shot glasses in a dilapidated vending booth. She has a lot of clients. As she tells it, people live in extreme poverty and they try to wash away their sorrow with alcohol.

Nina recounts in detail and with great enthusiasm about her 19-year work experience at the electric welding plant, about how good life was and how things have changed.

The doldrums of the social routine can be sensed at every turn in Ponichala: in the family of Karlo Zardiashvili, 98, residing on Surguladze street, who have their daily meals at a canteen for the underprivileged; in the poorly dressed teenagers playing in the yard, as well as in the rusty color facades of the private houses.

Early in the morning, Ponichala residents rush en masse ‘to the city.’ Many of them work at merchandise or food markets. After eight o’clock in the evening the public transport is fully packed with people. The new Rustavi taxis are a great relief for the population. They work till late at night and pass lower Ponichala.

The city’s blare and bustle hardly reaches upper Ponichala. Once you come here for the first time, you have a strange feeling like being outside of the city, but not quite in the village. This feeling is further intensified by the plots and vegetable gardens, expertly furnished in the paved courtyards between the blocks of flats. Here, no one will be surprised at seeing cows stately wandering down the road or an antique ‘Zhiguli’ car trick-riding in the street.

It’s getting dark. I am travelling from Ponichala via the Rustavi taxi. The passengers are sitting in silence. A cheerful group of tourists in the manicured streets of Old Tbilisi attracts the passer-by’s attention and, for some reason, the contrast of Tbilisi’s outskirt ‘country,’ Ponichala, and the city itself becomes twice as distressing.

Published:25.04.2016