Multipolar world: the US, China, Russia, SCO, BRICS and peace between Azerbaijan and Armenia

Peace process between Azerbaijan and Armenia

In recent months, talks on a peace agreement between Azerbaijan and Armenia have visibly intensified. Several meetings have been held with Washington’s mediation, while China has invited the leaders of both countries to high-level events and military parades in Beijing.

These parallel initiatives suggest that the local confrontation in the South Caucasus is becoming a point of competition between global powers. The “unipolar world order” that emerged after the cold war has been gradually shifting in recent years.

Power centres such as Russia and China are seeking to reshape the international order, using platforms like the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation and BRICS to balance Western influence.

“Azerbaijan’s interest is not political; it is solely an effort to strengthen economic ties”

Reuters notes that the security-focused Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO), once a bloc of six states, has expanded in recent years to 10 permanent members and 16 partners and observers. Its activities have gone beyond security and counterterrorism to cover economic and military cooperation.

Beijing has given these platforms strong ideological backing. President Xi Jinping has called BRICS “a pillar in building a multipolar world,” highlighting its role in promoting inclusive globalisation.

In practice, BRICS has gained weight after expanding to include Egypt, the UAE, Iran, Argentina and Ethiopia.

Today, the bloc represents about half the world’s population and up to 30% of global GDP.

With its growing significance, more than 30 countries — including Azerbaijan — have expressed interest or filed official applications to join.

This reflects the international system’s gradual move toward a multipolar model.

Yet local experts argue that Baku sees these geopolitical shifts less through an ideological lens than through pragmatic interests.

Political analyst Elkhan Shahinoglu said: “Russia and China want to use the SCO and BRICS to challenge the unipolar world order. That is not our concern. Azerbaijan’s interest in these organisations is solely about strengthening economic and trade links, and ensuring that member states make use of Azerbaijan’s transport potential.”

In other words, Baku’s main goal is to draw geo-economic dividends from great power rivalry rather than take sides in ideological blocs.

Nevertheless, the peace process in the South Caucasus is already clearly within the sphere of interest not only of the countries in the region but also of several major powers.

How does superpower competition affect this process? What “cards” are the US and China playing in the region, and where do Baku and Yerevan position themselves in this balance of power?

The answers to these questions are key to understanding the prospects for a peace deal.

The U.S. is presumably seeking to neutralize the influence of Russia and Iran in the South Caucasus

Washington has recently become an active mediator in the peace process between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Since 2023, US officials have organised several meetings with the leaders and foreign ministers of both countries.

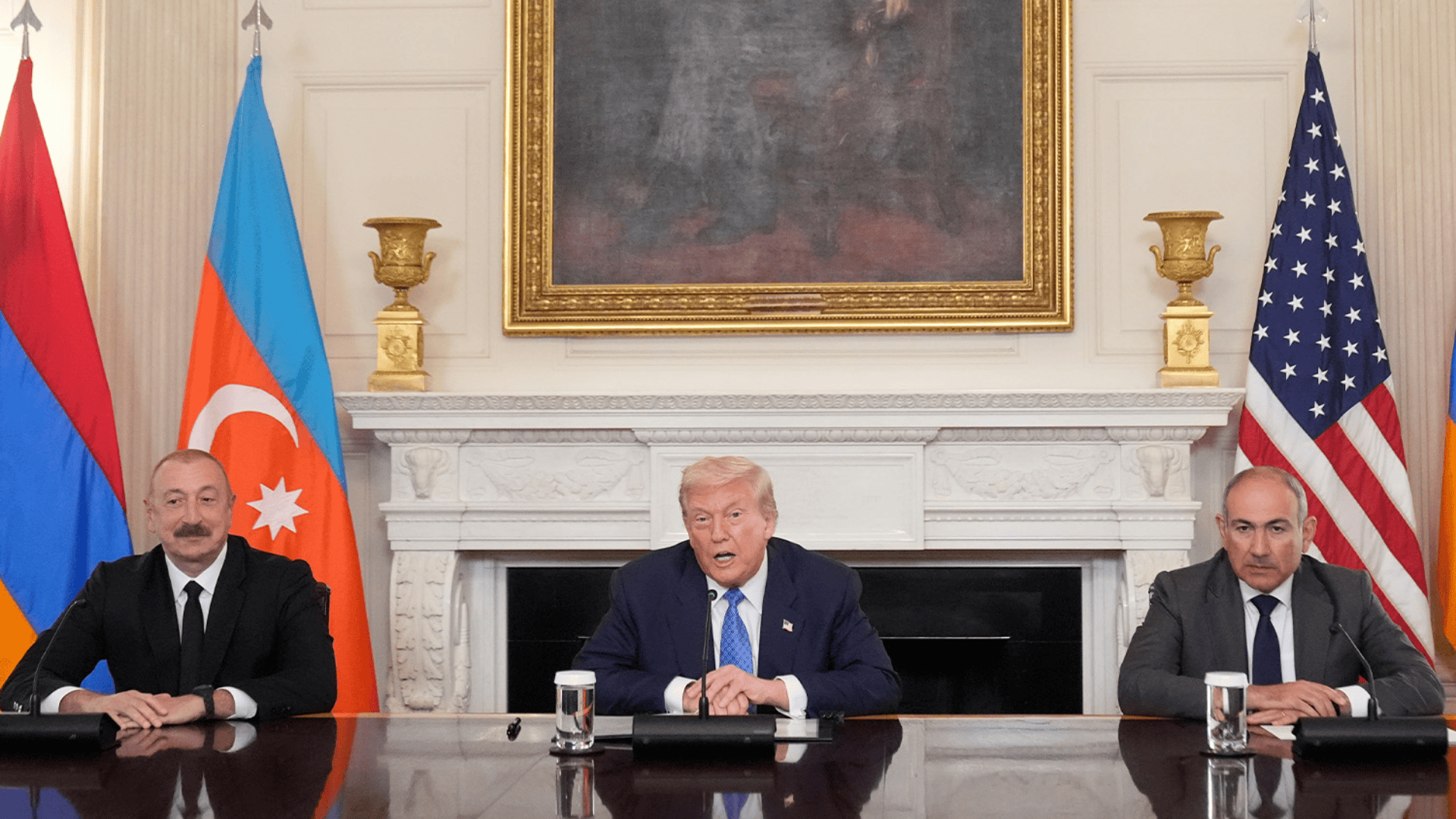

Talks held in Washington, and the signing of a preliminary peace declaration in the US capital in August 2025, point to America’s growing influence in the region.

Prime minister Nikol Pashinyan’s close contacts with the West — including joint military drills with the US and agreement to host an EU monitoring mission in Armenia — have created conditions for open backing from Washington.

The US’s main goal is to weaken Russia’s influence in the South Caucasus and protect strategic routes by strengthening regional stability.

For example, American diplomats have repeatedly expressed support for the opening of a transit route that would connect Azerbaijan with its autonomous region of Nakhchivan and further with Turkey through Armenian territory.

In Azerbaijan, this route is called the ‘Zangezur Corridor.’ At the meeting of the leaders of Azerbaijan and Armenia in Washington on August 8, attended by Donald Trump, an agreement was reached to open this transit route with the involvement of American companies, and the road was named the ‘Trump Route’ – TRIPP.

The main U.S. interest in this project, apparently, is to weaken Russia’s position in the South Caucasus by strengthening intra-regional economic integration.

American peace initiatives also send a signal to Iran and other outside players.

In the joint statement signed in August 2025 with US support, Washington stressed “the importance of opening transit corridors” in the region and pledged to “counter any harmful influence of third parties” in this area. In other words, the US aims to spur economic development in the South Caucasus, consolidate its influence over the proposed transit routes, and neutralise the negative interference of both Russia and Iran.

Washington’s mediation gives Pashinyan’s government the opportunity to obtain security guarantees from the West that Russia was unable to provide to Armenia. In Armenia, it is widely believed that Moscow failed to protect the Armenian population of Karabakh and cannot (and perhaps does not want to) meet Yerevan’s defense needs.

Pashinyan has admitted that “relying solely on one country (Russia) for Armenia’s security was a strategic mistake.”

Armenia has therefore deepened its security cooperation with the US and Europe.

Azerbaijan, for its part, has long worked with the US and NATO on areas such as energy security and counterterrorism.

On diversifying Europe’s energy supply, Baku and Washington share the same interest: the Southern Gas Corridor is a prime example of this strategic partnership.

The US supports a peace agreement in the region both for geopolitical reasons — reducing Russia’s influence — and for economic security. Washington sees conflict resolution as a way to reduce risks to trans-Caspian energy and transport projects and to speed up the South Caucasus’s integration with the West.

To pursue these goals, the US relies on political mediation (organising talks and high-level contacts) and limited military support, such as small-scale training programmes for Armenia. Ultimately, Washington is seeking to shape the peace process in the region through soft power and diplomatic leverage.

China: Support for both the ‘Zangezur Corridor’ and the ‘Crossroads of Peace’

Beijing’s role in the South Caucasus has grown noticeably in recent years, though in a different dimension — mainly through economic and infrastructure projects.

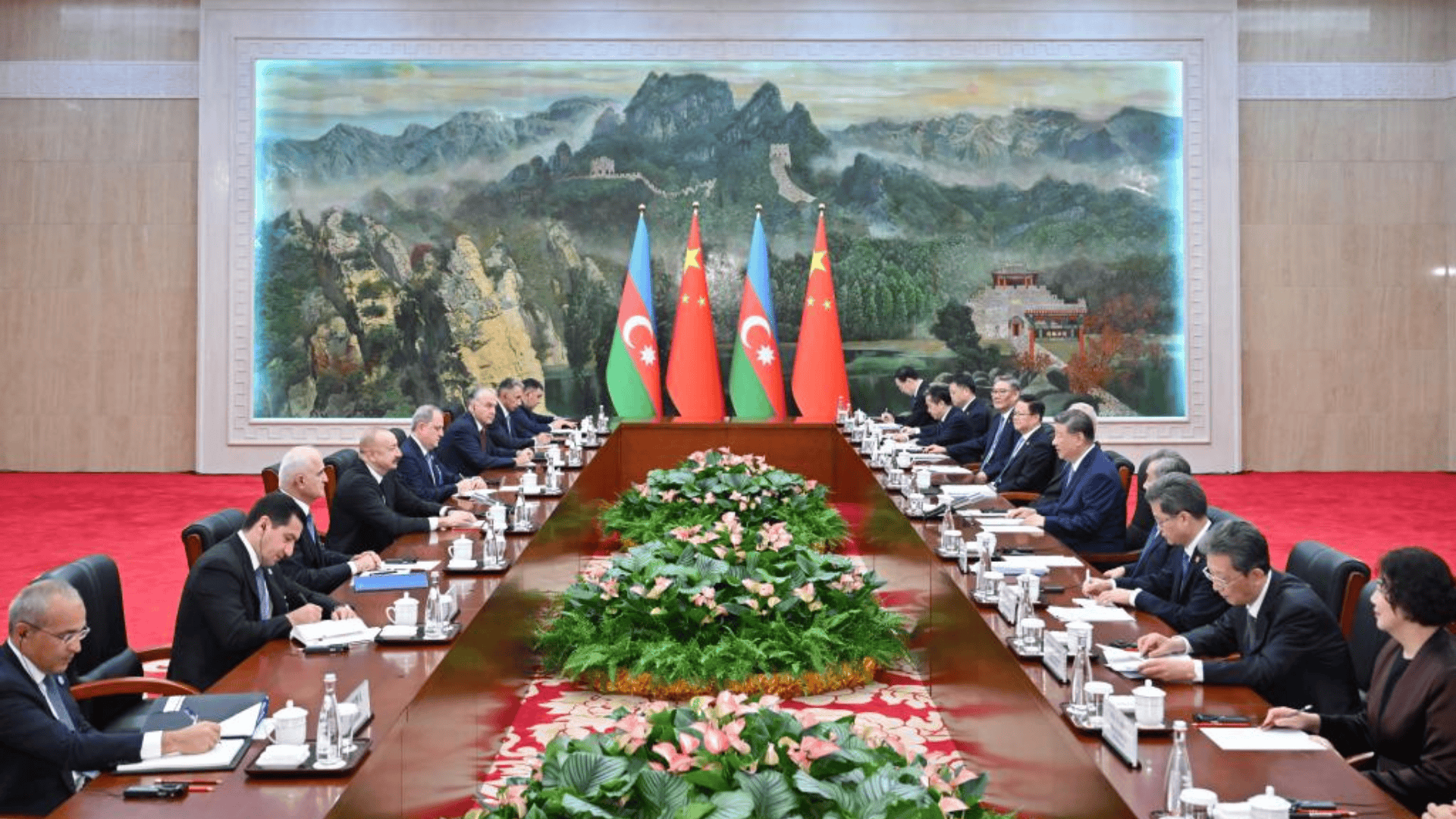

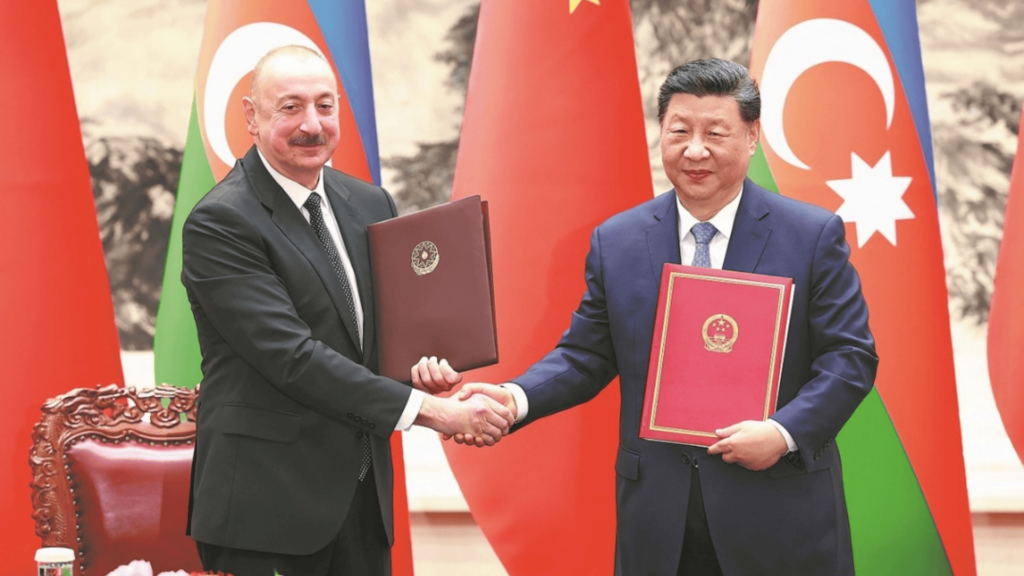

Between 2023 and 2025, Azerbaijani president Ilham Aliyev made several visits to China. He took part in Beijing’s Belt and Road Forum and, in August and September 2025, was an honoured guest at the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation summit and a military parade.

China presents itself as a neutral mediator: Beijing officially stresses its respect for the territorial integrity of both countries and avoids taking sides in the conflict.

At the same time, China shows a strong interest in integrating the South Caucasus into its wider Eurasian infrastructure plans.

The Middle Corridor, linking Central Asia with Europe, runs through Azerbaijan and is of strategic importance to China as an alternative trade route bypassing Russia.

Since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, cargo flows along the corridor have grown sharply. With the traditional northern route through Russia becoming less reliable under sanctions, the trans-Caspian route has gained appeal for logistics companies. This trend has pushed China to invest more actively in developing the Middle Corridor.

Chinese officials have put forward concrete initiatives to expand Azerbaijan’s transit potential. During a visit to Baku, Liu Jianchao, head of the international department of the Chinese Communist Party, said: “Azerbaijan has supported the Belt and Road Initiative from the very beginning, and Beijing is grateful for this.”

At the meetings, Chinese representatives particularly emphasized the importance of building the ‘Zangezur Corridor,’ noting that it would ‘further strengthen the link between Europe and Asia.’

Liu Jianchao, in particular, stated: ‘The Belt and Road Initiative and the construction of the Zangezur Corridor are important elements of the strategic cooperation between China and Azerbaijan.’ He added that Chinese companies should play an active role in the development of this route.

This shows that Beijing views the route as a geo-economic project. By using it, China would be able to shorten the Middle Corridor and secure another alternative route.

Armenia viewed the ‘Zangezur Corridor’ – and the very term ‘corridor’ – as a threat to its sovereignty and promotes its own alternative, the Crossroads of Peace.

Significantly, China has also officially endorsed this initiative and declared readiness to align it with the Belt and Road framework.

Beijing is therefore keen to build ties with both South Caucasus states.

Its main goal is for the region to be seen not as a source of problems but as a reliable transit hub.

To achieve this, China relies not on hard power but on the tools of the Belt and Road Initiative.

A series of strategic economic agreements between Azerbaijan and China have also been signed recently.

● In July 2025, the two sides concluded a comprehensive strategic partnership, under which China pledged to support the development of the Middle Corridor.

Baku hopes the deal will bring increased Chinese investment in Azerbaijani infrastructure, make the route more competitive, and strengthen the country’s role as a logistics hub.

● Chinese companies have already received proposals to take part in projects to build a new cargo port in Azerbaijan, develop the digital economy and expand metro lines.

Beijing has also begun showing soft power towards Armenia.

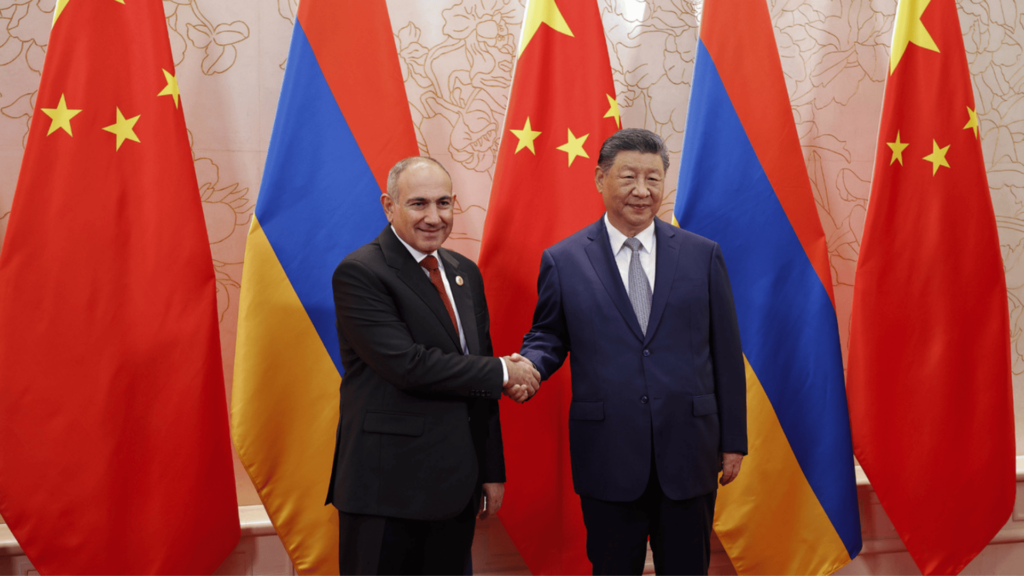

● A few days ago, during the SCO summit, Armenia and China signed a strategic partnership agreement.

● China has also said it welcomes Armenia’s participation in the SCO.

Even so, the Chinese factor is not yet decisive for Yerevan. China’s share in Armenia’s foreign trade and investment inflows remains limited.

Relations between Beijing and Yerevan are largely at the level of political gestures – for example, Armenia’s government backed China’s territorial integrity in a statement against Taiwan’s independence, while Beijing in turn stressed its respect for Armenia’s sovereignty.

In other words, China’s main focus for now is on Baku.

Overall, China pursues a policy of “soft neutrality” in the South Caucasus.

Without openly taking sides, it draws both countries into cooperation through major economic incentives.

Regional stability and the opening of transport routes form part of China’s wider global projects. For this reason, Beijing avoids steps that could harm the peace process; instead, it sees a possible agreement as an opening to advance its own initiatives.

The growing role of China gives both Baku and Yerevan an extra lever to reduce dependence on Moscow, offering them an alternative major partner. In the longer term, as countries in the region expand their room for geopolitical manoeuvre, they will be able to make more independent decisions in the interests of peace.

Azerbaijan’s position

For years, Azerbaijan has pursued a balanced foreign policy. President Ilham Aliyev’s strategy of maintaining parallel ties with Russia and Iran, on the one hand, and with the West and emerging power centres on the other, has given Baku room to manoeuvre.

This “multi-vector” approach allows Azerbaijan to reap benefits without tying itself fully to any single pole. It has enabled the country to shift closer to or further from different powers as circumstances required, while preserving its own interests.

In practice, this has meant promoting energy projects with the West in the 2010s, signing a declaration on allied cooperation with Moscow in 2022 and stepping up military ties, yet at the same time remaining neutral over the war in Ukraine — refusing to join sanctions but sending humanitarian aid to Kyiv.

Such flexibility helps Baku avoid risky alliances and preserve independence in decision-making.

Azerbaijan’s new direction

In the past year, Azerbaijan has deepened its ties with China and other fast-growing economies. In summer 2024, Baku applied to upgrade its status in the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation (SCO) from dialogue partner to observer, and soon after formally applied to join BRICS.

At the same time, Azerbaijan continues to chair the Non-Aligned Movement and maintain an individual partnership programme with NATO.

Baku is working to align the interests of both the US and China without letting them clash. It is a strategic energy partner for the West, supplying gas to Europe and oil to Israel, while also serving as a transit route to Asian markets.

For example, Azerbaijan is both part of a new “green” energy corridor project with Europe — transmitting electricity from the Caspian to the Black Sea — and a participant in China’s “Digital Silk Road.” Its infrastructure, including the Baku port and the Baku–Tbilisi–Kars railway, is open to both Western and Chinese projects.

Azerbaijan seeks backing from both Washington and Beijing for the Zangezur corridor, while signalling to Moscow that it now has many alternatives and that Russia’s leverage is weaker than before.

Russia’s decline due to sanctions and the war in Ukraine has given Baku more room to manoeuvre. After 2020, Russian peacekeepers were deployed in Karabakh, but in 2023 Azerbaijan reasserted full control over the region without their involvement — showing Moscow could no longer dictate outcomes. Pashinyan himself remarked that Russia was “gradually leaving the region.”

This environment allowed Azerbaijan to take key steps, such as controlling the Lachin road and disarming armed groups in Karabakh, without Moscow’s consent. Still, Baku avoids appearing openly anti-Russian: it continues coordination with the Kremlin, for example by informing Moscow during peace agreement talks with Armenia.

Ultimately, Azerbaijan aims to use the rivalry between the US and China to secure a peace deal that maximises its sovereign interests, strengthens its role as a regional centre and avoids open confrontation with any major power.

Armenia’s position

In recent years, Armenia has undergone a sharp geopolitical shift. Prime minister Nikol Pashinyan came to power with the image of a reformer oriented toward the West, but after the 2020 Karabakh war he initially tried to lean on Russia. That alliance fell short of expectations: after the 2020 ceasefire Moscow failed to fully defend Armenia’s interests, and in 2022–23 it offered no real support in border clashes with Azerbaijan — pushing Pashinyan to look for new options.

By 2023, Armenia’s leadership had moved to openly criticising Moscow. Pashinyan admitted that excessive reliance on Russia was a strategic mistake and announced a diversification of security approaches. Against this backdrop, Armenia improved ties with the US and Europe and began seeking new partners in the region.

The country’s rapprochement with the West has taken several forms. First, since 2022 Armenia has hosted an EU civilian monitoring mission on its borders, later extending its mandate until 2027. This was a clear signal of departure from the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO), which had disappointed Yerevan during the border crisis of 2021–22.

Second, in September 2023 the Armenian army held joint exercises with the US — the first large-scale drills of their kind, which drew sharp protests from Moscow.

Third, Pashinyan’s government ratified the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court, creating legal risks for visits to Armenia by Russian leaders, including Vladimir Putin. Together, these steps pointed to Yerevan moving out from under Moscow’s security umbrella.

At the same time, Armenia has sought stronger political and diplomatic backing from Europe and the US. A visit to Yerevan by then US House speaker Nancy Pelosi and a trip by the French foreign minister to frontline areas raised hopes in Armenian society of greater Western support.

Pashinyan has placed particular emphasis on negotiations in the Brussels format mediated by European Council president Charles Michel. In his view, Russia-led talks tend to foreground Kremlin interests, whereas Western mediation is more respectful of Armenia’s sovereignty.

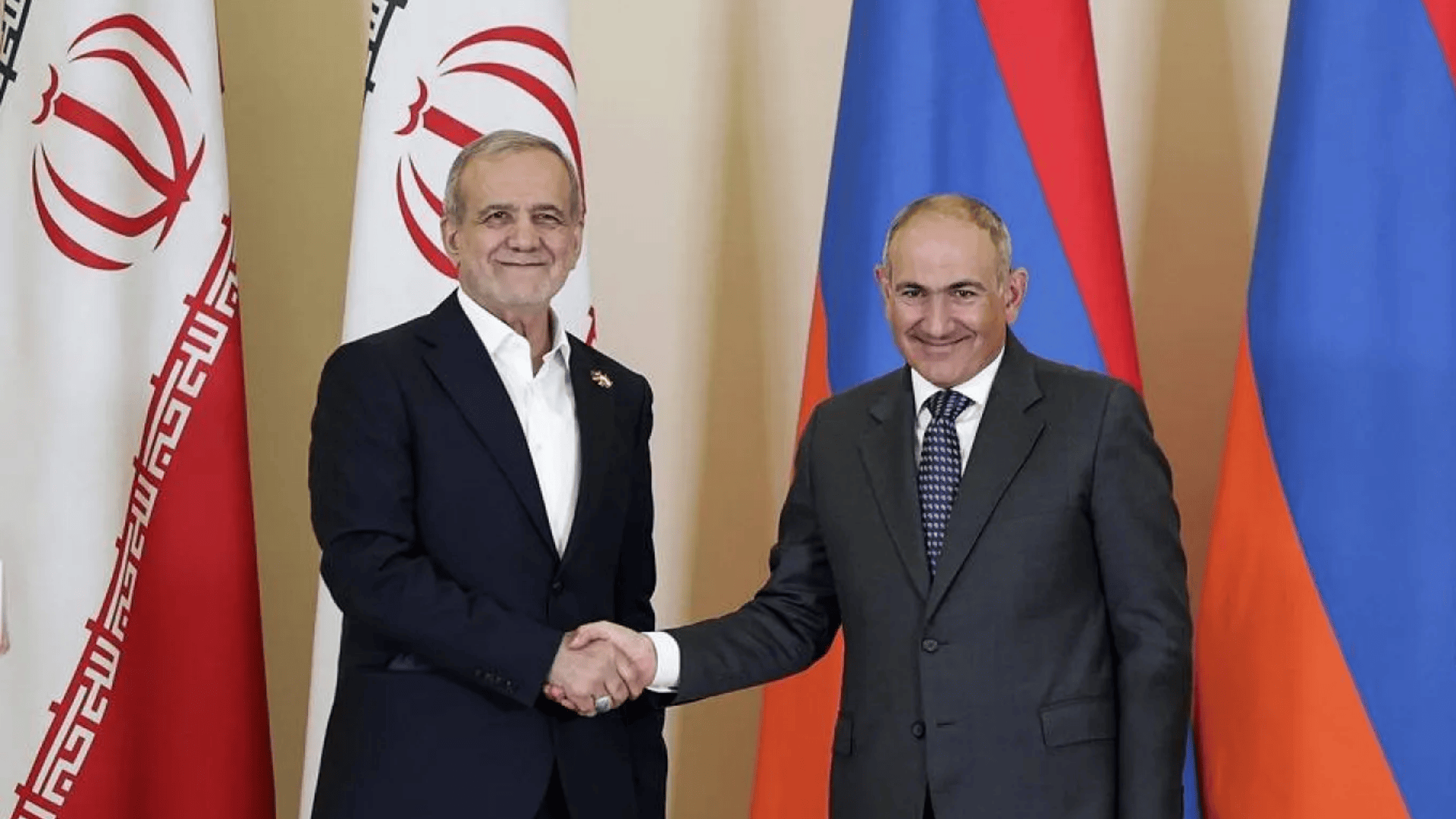

In recent months, Armenia has also moved to strengthen ties with China. This summer, the country for the first time signalled at a high level its interest in joining the Shanghai Cooperation Organisation. During a visit to Beijing, foreign minister Ararat Mirzoyan announced Armenia’s intention to join the SCO, and the two sides agreed to upgrade bilateral relations to a comprehensive strategic partnership.

In August this year, Pashinyan met Xi Jinping in Tianjin during the SCO summit in China, and the two leaders issued a joint statement pledging to refrain from steps that could undermine each other’s sovereignty.

Armenia is seeking new trade routes for direct access to the Chinese market via Georgia and Central Asia, as well as links to the Indian Ocean through Iran and logistics agreements with Central Asian states. For now, these remain plans on paper.

In the short term, Russia still plays a role in Armenia’s security system. The 102nd Russian military base in Gyumri guards Armenia’s border with Turkey, while Russian companies retain a large share in Armenia’s energy and transport sectors. Pashinyan has said that Armenia does not plan to leave the CSTO but continues to criticise its effectiveness.

At home, a Russia-oriented political and social layer remains influential. Moscow has recently cut off arms supplies and created customs barriers, signalling displeasure with Yerevan’s turn to the West.

Pashinyan’s government hopes to stabilise the situation by securing a peace agreement and opening borders. If conflict with Azerbaijan ends, Armenia’s need for Russian “protection” will diminish, allowing the country to pursue development with Western support and investment from major powers.

Conclusions

Global competition has added both risks and opportunities to the peace process between Azerbaijan and Armenia. Rivalry among major powers can push mediators to work harder, as happened by mid-2023 when parallel talks in Brussels, Washington and Moscow helped move the draft peace deal forward. But history shows the dangers too: in the 1990s, the Karabakh conflict stayed frozen largely because of Western–Russian rivalry.

Today the risks are clear. If Moscow feels fully sidelined, it could try to derail any settlement — for example by backing separatist forces or creating new pressure points. A sharper confrontation between Washington and Beijing could also leave Baku with difficult choices if sanctions or economic dependency come into play.

For now, though, the outlook is more positive. The US seeks peace to weaken Russia’s influence, while China wants long-term stability to protect its investments. Their interests in this area converge, not clash. Beijing even welcomed the Washington agreement signed in August 2025 as “a step that promotes development.”

Whether the South Caucasus becomes a platform for cooperation in a multipolar world will depend on how Baku and Yerevan use this moment. The key to peace remains in the hands of local leaders; major powers can smooth the way or block it, but balance and pragmatic diplomacy are still the strongest tools for small states.