Femicide in Georgia: a chronicle of tragedy

Murder instead of divorce

30-year-old Natia Gogoladze in 2016 left for Italy to earn money to feed two children. So many Georgian women are forced to do, desperate to find work in their homeland.

Natia returned to Georgia six months ago. With the money she raised in Italy, she opened a small second-hand clothing store in her hometown of Khashuri.

•‘Women’s march’ conducted in Tbilisi. Photo report

•Georgia’s favourite TV show – how ‘My Wife’s Girlfriends’ won the hearts of viewers

•Turkey: murder and violence against women on the rise

On October 11, Natia’s ex-husband Irakli Dekanoidze came to this store. First, he threw a grenade into the room, which did not explode. Then he shot at her several times, and Natia, in horror, tried to run away.

Her ex-husband caught up with her and hit her with the pistol grip several times. Natia died the same day in the city hospital

This terrible story is retold by Keti, Natia’s childhood friend. The girlfriends had not seen each other for two years, since both left for work – one to Italy, the other to Turkey.

Keti returned home when she learned about the murder of Natia.

“We were going to celebrate New Year’s together. Like in childhood,” says Keti.

Natia got married at 16, Keti says – for love. But the relationship quickly deteriorated.

“I think she was happy with her husband for a year. Then came the problems – economic difficulties, physical and emotional abuse. They diverged, then reconciled. The last five years they had not lived together,” says Keti.

On October 11, 2019, on the day of the murder, the court was to consider Natia’s divorce statement. Irakli killed his wife a few hours before the scheduled trial. He was arrested on the same day.

Natia was buried on October 15 in her hometown. During the funeral, her 11-year-old son was quickly taken away from the gravesite, while her 13-year-old daughter said goodbye to her mother for a long time.

Now the fate of the children will be decided in court. Now they live with their grandmother, the mother of their mother, and an aunt.

But their father’s family will also defend their right to guardianship. The father himself may be deprived of parental rights – social workers have appealed to the court with such a petition.

Is the state an accomplice?

On July 25, 2014, police inspector Sergi Satseradze and his ex-wife, 19-year-old Salome Jorbenadze, were talking about something while sitting on a bench in the central park of Zestafoni.

Suddenly, Satseradze pulled out a gun and shot his ex-wife, firing at her five times. Then he left, but soon returned, called the police and surrendered to the authorities.

Salome married 22-year-old Sergi at the age of 16.

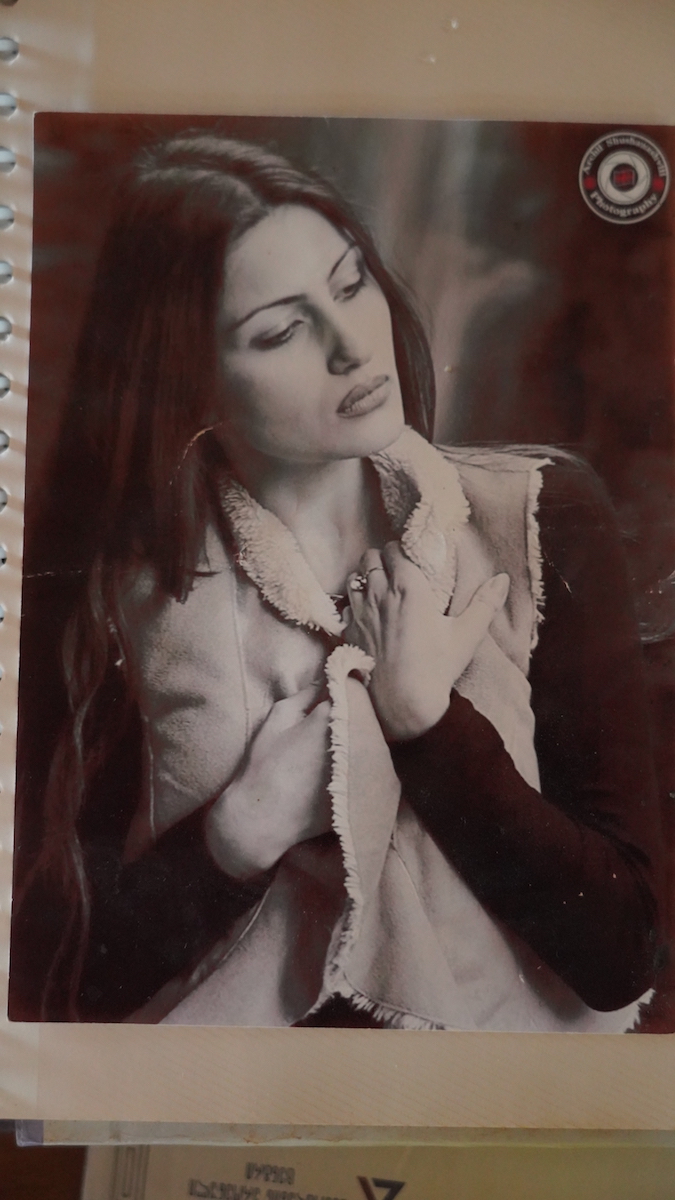

She was a bright popular girl in the small town of Zestafoni – she participated in beauty contests and had many admirers.

“Salome was very proud of her appearance, she liked being a model,” Fati Jorbenadze, the mother of Salome, says of her daughter.

One day, Salome went to her friend’s birthday, from where Satseradze “abducted” her and lured her into her car, announced that now she would be his wife and took her home.

One day, Salome went to her friend’s birthday, from where Satseradze “abducted” her and lured her into her car, announced that now she would be his wife and took her home.

This method of “marriage” is becoming less common in modern Georgia.

Abduction of a person for any purpose is a serious crime for which the criminal code provides for up to eight years in prison.

However, Salome’s parents did not sue Sergi because their daughter agreed to marry him – that is, to live with him as a de facto wife (because de jure marriage is impossible until the age of 18).

Today, her mom says that Salome stayed in the kidnapper’s house only because he threatened her with weapons.

Salome’s mother is a youthful brunette. Like many Georgians who have lost loved ones, on her chest she wears a medallion with a photograph of her young daughter.

“When she was 13 years old, my husband and I had an accident. I was bedridden for three months — I could neither walk nor get up. Salome took care of me – she fed, bathed, and even made me up.”

The house is full of reminders of Salome – her photographs and things are everywhere.

In Salome’s room on the bed are her clothes, drawings and notebooks, her letters and poems.

Now in this room are Salome’s mother and her seven-year-old son Sandro.

“My daughter lived in fear and quarrels all the time,” Fati says. “[Her husband] forbade her from talking to her family or going to school.”

Salome managed to get away from Sergi and return to the parental home shortly after the birth of her son. Satseradze did not want to give up – he was jealous, came to her house, threatened and made scandals.

Several times the family turned to the police, prosecutors and the Ministry of Internal Affairs, but in vain – the investigation was endlessly delayed.

The parents of the murdered girl are convinced that the law-enforcement structures covered for Satseradze because he was police personnel.

Not only was he not punished – he was promoted.

This promotion, which happened a few days before the tragedy, Fati considers fatal – it seemed to have convinced Satseradze of his innocence.

In the end, the killer was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

“She wanted to become a prosecutor, she said that then she would protect herself. And she said that she would definitely become a celebrity. Who would have thought what exactly her fame would be,” says Salome’s mother.

Frightening statistics

Five years have passed between the killings of Salome and Natia. Since then, 87 women have been killed by husbands or partners in Georgia.

The statistics for 2019 have not yet been published, but it is already clear that there will be no reason for optimism – not a month passes in Georgia without reports of domestic violence that end in the death of a woman.

Human rights activists call such murders femicide – that is, the murder of a woman by a man due to anger or hatred.

Despite the fact that there are many such crimes in Georgia, the concept of femicide has not been fixed legally anywhere – despite numerous attempts by the women’s movement, the parliament has not adopted a bill.

Representatives of the women’s movement demand that the word “femicide” be included in the Georgian Penal Code and be interpreted as the intentional murder of a woman committed by her husband, ex-husband, partner or former partner.

Under the current penal code, gender-based crime is an aggravating circumstance. However, human rights defenders are confident that only one allocation of femicide as a separate article will no longer allow the prosecutor to ignore the real motive of the crime when charged, as is often the case now.

Restraining orders don’t help

The stories of femicide victims in Georgia are very similar – early marriage, jealousy on the part of her husband, physical and psychological violence that women have suffered for years.

Experts immediately attribute a whole range of problems to the causes of femicide.

One of the main ones, according to human rights activists, is that despite almost a hundred dead women, Georgian law enforcement officers are still not serious enough about the manifestations of domestic violence.

At the same time, the Ministry of Internal Affairs claims that combating domestic violence is a priority.

In a statement on the website of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, it is alleged that it was this agency that initiated changes to legislation in late 2018 to toughen punishment for domestic violence.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs also set up a hotline for victims of violence and a state shelter where victims can receive protection for up to six months.

But, as it turns out in practice, law enforcement agencies are often not able to protect women who turn to them for help.

Studies confirm that most of the women killed by husbands before the tragedy went to the police. That is, the law enforcement authorities knew about the violence, but did not protect the victim. That was the case with both Salome and Natia.

Salome’s mother recalls that the last time her daughter complained about her husband to the prosecutor’s office literally on the day of the murder.

“The police confused her, and she was bewildered, in her statement softened what she really said. However, Salome wrote that her husband is still abusing her,” says Salome’s mother.

She is convinced that the state could have saved the life of her daughter, but did not.

A few months before Natia’s murder, the police wrote out a security order, a document that forbade her husband from approaching her. This happened after another quarrel, says Keti. He husband hit Natia with a jug on the head – she had to get stitches.

“She ran straight barefoot to the police. They all wrote down and issued a restraining order.”

Security orders appeared recently in Georgia and at first they were considered almost a solution to the problem. But it soon became clear that this paper could not always protect the victim.

Until November 2018, a violation of the security order was punishable only by administrative arrest for seven days. Now this is a criminal offense punishable by jail for up to a year, and if repeated, up to three.

One hundred bracelets

Now the state is trying another initiative that may prevent violence against women – electronic bracelets.

Such a bracelet is put on the wrist of a person convicted of violence, so that law enforcement officers can monitor their movements and can intervene promptly if they approach the victim.

So far, this initiative has not worked, because parliamentarians are only preparing to consider the corresponding bill.

The Ministry of Internal Affairs developed it in collaboration with UN Women.

Unfortunately, it will be impossible to use the bracelet on all restraining orders – the Ministry of Internal Affairs has only a hundred of them at its disposal, and this is not comparable with cases of domestic violence.

For example, in 2018 alone, the Ministry of Internal Affairs issued more than 7,600 orders.

The Georgian budget is not yet able to support such a purchase.

One set of electronic surveillance equipment costs $2,820. The Ministry of Internal Affairs received funds for 100 sets from UN Women.

It is assumed that starting in 2021 the Georgian state will take these costs upon itself.

Baia Pataraya, chairman of the Sapari women’s human rights organization, believes that electronic bracelets are an important step in preventing femicide:

“If the rapist is not arrested, he should be strictly controlled. Obviously, a security order does not provide this, so an electronic bracelet will be a release for many women,” says Baia Pataraia.

Thanks to the work of activists, Georgia has adopted a number of progressive laws and ratified several key conventions. In 2014, the Georgian parliament ratified the Istanbul Convention against Violence against Women. Parliament has also passed a law on sexual harassment.

The laws are good, activists say, they are based on the very useful experience of Western countries, but, alas, often they simply do not work.

Human rights activists believe that the main problem is the inefficiency of the police and prosecutors.

Another guilty party – the public

Femicide researchers say violence against women in Georgia is caused by low levels of education, social and economic problems, and cultural and religious traditions.

Even today, many in Georgia do not realize that domestic violence is a crime and do not consider it necessary to intervene in a family conflict and protect a woman from a rapist. Some victims do not go to the police, believing that “family disagreement is a family matter.”

In television stories about cases of femicide, one can often hear the comments of neighbors, relatives and eyewitnesses accusing the victim, not the murderer, of what happened.

“What can you expect if you argue with your husband and don’t obey him?” – such a remark was made in a recent story about one of the most recent murders of a young woman.

Human rights activists emphasize that it is often journalists who propagate the stereotypes while discussing femicide.

They may call the cause of the murder ‘jealousy’ or clarify that the victim “had someone else” – which in turn can be regarded as an indirect justification for the killer’s behavior.

According to Tamara Tskhadadze, a professor at Ilia State University, one of the reasons for femicide is the norm of masculinity in Georgian society, which links the dignity of a man with the sexual behavior of his partner.

“Violence is directly related to power. And there is no doubt that men have more power over women, and they consider themselves entitled to force them … Women are perceived as sexual objects, and not as independent entities. That is, a woman has no right to initiative or choice in sexual matters, and if she takes the initiative, she will be punished,” says Tskhadadze.

If you analyze the cases of femicide in Georgia, you will find that often the victims are women who decide to change something in their life contrary to the wishes of their husbands.

For example, they decide to divorce their husbands and live independently.

“Husbands and relatives do not allow a woman to start living independently. To this day, it is believed that a woman should be obedient, take care of others, obey her father, brother or husband, and as soon as she takes her own initiative, she will meet with great resistance,” says Baia Pataraia.

Professor at Ilia State University Emzar Jgerenaia, believes that problems begin with raising children in the family:

“Parents look with approval at the sexual activity of their sons, are proud if they have many partners, but daughters do not have such rights. The sister is still obligated to iron her brother’s clothes, cook food for him, etc. This standard in families must be destroyed. Parents must explain to their children what freedom means to both boys and girls.”

According to Baia Pataraia, the state does little to defeat these cultural stereotypes:

“We need the empowerment of women, which requires deep reform, starting with the education system – women should be told about their rights in school. Women need to be given more opportunities economically and politically, and the state should have a concrete plan of action. We may be passing the necessary laws, but in this regard we are seriously lagging,” she says.